Jan Van Eyck was a Flemish painter born 1390 in Maaseik, Belgium and died 1441 in Bruges, Belgium. Eyck was associated with the Renaissance, Flemish School (Ars Nova) movement. Famous paintings and artwork of this artist include Arnolfini et sa femme and Vierge au chancelier Rolin.

Jan van Eyck is considered to be a founder of the Early Renaissance style in the Northern Renaissance. Until 1425 Jan van Eyck served at the court of Duke Johann of Bavaria in Hague, painting and restoring pictures. After that, he served at the court of Philip the Good of Burgundy, where he was greatly valued not only as an artist, but he also was entrusted by Duke with various diplomatic missions. Since 1430 van Eyck lived and worked in Bruges as painter to the court and city. It was believed, that Jan van Eyck invented painting with oils, maybe it is not true, but his technique in painting with oils is exceptional. His paint is so transparent that his works have a unique, almost luminous sheen. So outstanding was his skill as an oil painter that the invention of the medium was at one time attributed to him. Van Eyck exploited the qualities of oil as never before, building up layers of transparent glazes, thus giving him a surface on which to capture objects in the minutest detail and allowing for the preservation of his colours.

Jan Van Eyck was a Flemish painter born 1390 in Maaseik, Belgium and died 1441 in Bruges, Belgium. Eyck was associated with the  Renaissance, Flemish School (Ars Nova) movement. Famous paintings and artwork of this artist include Arnolfini et sa femme and

Renaissance, Flemish School (Ars Nova) movement. Famous paintings and artwork of this artist include Arnolfini et sa femme and

Jan van Eyck, the most famous and innovative Flemish painter of the 15th century, is thought to have come from the village of Maaseyck in Limbourg. No record of his birthdate survives, but it is believed to have been about 1390; his career, however, is well documented. He was employed (1422-24) at the court of John of Bavaria, count of Holland, at The Hague, and in 1425 he was made court painter and valet de chambre to Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy. He became a close member of the duke’s court and undertook several secret missions for him, including a trip (1428-29) to Spain and Portugal in connection with negotiations that resulted in the marriage (1430) of Philip of Burgundy and Isabella of Portugal. Documents show that in 1432-33 van Eyck bought a house in Bruges. He signed and dated a number of paintings between 1432 and 1439, all of which are painted in oil and varnished. According to documents, he was buried on July 9, 1441.

Van Eyck has been credited traditionally with the invention of painting in oils, and, although this is incorrect, there is no doubt that he perfected the technique. He used the oil medium to represent a variety of subjects with striking realism in microscopic detail; for example, he infused painted jewels and precious metals with a glowing inner light by means of subtle glazes over the highlights. Van Eyck’s most famous and most controversial work is one of his first, the Ghent altarpiece (1432), a polyptych consisting of twenty panels in the Church of St. Bavo, Ghent. On the frame is an incomplete inscription in Latin that identifies the artists of the work as Hubert and Jan van Eyck. The usual interpretation is that Hubert van Eyck (d. Sept. 18, 1426) was the brother of Jan and that he was the painter who began the altarpiece, which Jan then completed. Another interpretation is that Hubert was neither Jan’s brother nor a painter, but a sculptor who carved an elaborate frame for the altar. Because of this controversy, attribution of the panels, which vary somewhat in scale and even in style, has differed, according to the arguments of scholars who have studied the problem.

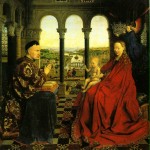

Equally famous is the wedding portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife (1434; National Gallery, London), which the artist signed “Johannes de Eyck fuit hic 1434” (Jan van Eyck was here), testimony that he witnessed the ceremony. Other important paintings are the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (1433-34 Louvre, Paris) and the Madonna of Canon van der Paele (1436; Groeningen Museum, Bruges). An Van Eyck (IKE) was born in the Netherlands. His paintings are very detailed. He was not the first to use oil paint, but he perfected the use of oil in paints. The colors in his paintings are delicate and have a beautiful shine. He was called “The King of Painters” by people even hundreds of years after his time.

The painting we are studying; The Arnolfini Marriage , is a record of the marriage of the two people in the picture. In modern days, a couple would hire a photographer to record their wedding. Giovanni Arnolfini hired an artist to paint the picture. In addition to being a portrait, it is also a legal record showing that the marriage took place. The artist signs it as a legal document. It is thought that Jan Van Eyck had a brother named Hubert. Supposedly, the famous Ghent Altarpiece was started by Hubert and finished by Jan after his brother’s death. This magnificent painting is very large; two stories high and painted in three parts. It is called a triptych (TRIP tik) because it is a picture in three panels. An van Eyck is the most famous member of a family of painters traditionally believed to have originated from the town of Maaseik, in the diocese of Liège. The work of the van Eycks, epitomized in the Ghent Altarpiece, brought an unprecedented realism to the themes and figures of late medieval art.

Van Eyck pursued a career at two courts, working for John of Bavaria, count of Hainaut-Holland (1422-24), and then securing a prestigious appointment with Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy (1425-41). Employment at court secured him a high social standing unusual for a painter, as well as artistic independence from the painters’ guild of Bruges, where he had settled by 1431. Evidence that the van Eycks bore a coat-of-arms, and thus belonged to the gentry, and that Jan was literate (as shown by his own handwriting on a drawing), is consistent with the probability that some of his frequent travels for the duke were diplomatic missions. Many aspects of his work were surely intended to promote his personal reputation and abilities, including his practice of signing and dating his pictures (then unusual), and his playful and quasi-erudite use of Greek transliteration in his personal motto Als ich kan (As well as I can). His artistic prestige rests partly on his unrivaled skill in pictorial illusionism. The landscape of his Crucifixion (32.92ab), with its rocky, cracked earth, fleeting cloud formations, and endless diminution of detail toward the blue horizon, reveals his systematic and discriminating study of the natural world. Van Eyck’s ability to manipulate the properties of the oil medium played a crucial role in the realization of such effects. From the fifteenth century onward, commentators have expressed their awe and astonishment at his ability to mimic reality and, in particular, to re-create the effects of light on different surfaces, from dull reflections on opaque surfaces to luminous, shifting highlights on metal or glass. Such effects abound in the Virgin of Canon van der Paele (1434–36), as shown by the glinting gold thread of the brocaded cope of Saint Donatian, the glow of rounded pearls and dazzle of faceted jewels in the costumes of the holy figures, or the small, distorted reflections of the figures of the Virgin and Child repeated in each curve of the polished helmet of Saint George. The almost clinical detail in the face of the kneeling patron vividly illustrates van Eyck’s acute objectivity as a portraitist.

Through his understanding of the effects of light and rigorous scrutiny of detail, van Eyck is able to construct a convincingly unified and logical pictorial world, suffusing the absolute stillness of the scene with scintillating energy. Despite this legendary objectivity, van Eyck’s paintings are perhaps most remarkable for their pure fictions. He frequently aimed to deceive the eye and amaze the viewer with his sheer artistry: inscriptions in his work simulate carved or applied lettering; grisaille statuettes imitate real sculpture; painted mirrors reflect unseen, imaginary events occurring outside the picture space. In The Arnolfini Portrait, the convex mirror on the rear wall reflects two tiny figures entering the room, one of them probably van Eyck himself, as suggested by his prominent signature above, which reads “Jan van Eyck has been here. 1434.” By indicating that these figures occupy the viewer’s space, the optical device of the mirror creates an ingenious fiction that implies continuity between the pictorial and the real worlds, involves the viewer directly in the picture’s construction and meaning, and, significantly, places the artist himself in a central, if relatively discrete, role. Another reflected self-portrait, this time in the shield of Saint George in the Virgin of Canon van der Paele, functions as part of van Eyck’s textural realism but likewise challenges our credulity by reminding us, through this minor intrusion of the artist’s image, that his ostensible realism is an artifice.

Despite his individual fame, van Eyck’s achievement was not carried out in isolation: as was customary, he employed workshop assistants, who made exact copies, variations and pastiches of his completed paintings. Such works no doubt helped to supply a vigorous demand for his work on the open market, while contributing to the recognition of his name throughout Europe. After Jan’s death in June 1441, his brother Lambert, who was also a painter, helped to settle his estate, and perhaps oversaw the closing of his workshop in Bruges. Van Eyck’s principal artistic successor in Bruges was Petrus Christus. In his Portrait of a Carthusian (1446; 49.7.19), Christus not only adopted the Eyckian style, but also the motif of the parapet with illusionistic carving which curtails the portrait at the lower edge: van Eyck had used this device earlier in his portrait Leal Souvenir (1432).

Thank you for this, it really helped with understanding!