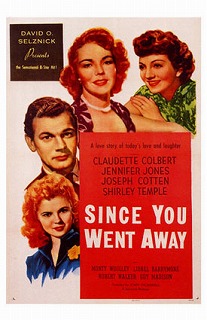

The film Since You Went Away was released in 1944. This epic film attempted to relate to the American audience that was dealing with the war foreclosing and the flux of soldiers coming home at the time. The Hollywood studios were constantly trying to do their part for the war buy making films about the war in a fairy tale “Hollywood” style.

Since You Went Away crossed these boundaries, and the movie audience at the time, positively responded for this reason. The producer and screenwriter of the film knew America craved this portrayal. Critics of the film from this period, applauded it’s “realism”, but in hindsight studies of the film in the seventies and eighties were a little more critical of the film. David O. Selznick was the man behind the vision of this film and Selznick is best known for film classics like; Gone With the Wind, (from which the formula of this movie draws heavily from) Rebecca, and King Kong. This film was a special project for Selznick at the time, and it was seen as his contribution to the war effort. The academy awards recognized Selznick’s effort and nominated his film for best picture of 1944. David Selznick was known as a one of the great creative producers- along side Walt Disney. A creative producer is usually “a powerful mogul who supervises the production of a film in such exacting detail that he was virtually its artistic creator.” (Eyman p. 121) In this period, Selznick’s style was remembered best by his epic length movies in which he paid special attention to detail. His films catered to the female market but also had potential to cross over to the male segment. Selznick was “increasingly becoming aware of the commercial value of his name.” (Fenster p.36) He decided to repeat the formula that worked well in Gone With the Wind and made a decision to purchase a war novel/diary from Margaret Wilder. Since You Went Away spawned from Wilder’s novel, after Selznick spent many hours on developing the screenplay and hiring the right cast. The war film was a popular genre to produce during the war years in North America.

Also, it was seen as a noble effort to make a film about the war. Most of the skilled directors or producers of these films, stylized their own vision of the war with their special trademarks throughout the film. Films that did this, usually did will well at the box office as well as at the Academy Awards Ceremony. David Selznick was looking for a hit movie to follow the success of Gone With The Wind and he hoped Since You  Went Away would be a blockbuster. Selznick spent nearly “$3,000,000 on this film”, (Thomas p. 220) which meant glossy and detailed scenes throughout the film. This was an unusual amount of money for a film from this period, but David Selznick was known in Hollywood for his elaborate budgets. The films length allowed Selznick to allow it to take place over a year. The story begins in January 12, 1943 which is immediately after Mr. Hilton departs for the war. The Hiltons are a middle/upper class family who are now faced with dealing with dealing with the trials and tribulations of everyday life without the support of a male authority figure. A lot of emphasis is placed on the female audience’s familiarity with “the details of day to day living and plenty of humorous sentimental reportage of housekeeping: rationing, the problems of two growing daughters and the business of getting jobs to help the family’s reduced budget.”(Hartung p 374) Selznick increased the original ages of the two daughters so Shirley Temple (Bridget) and Jennifer Jones (Jane) could play the roles and romance could be introduced. Nineteen forty-four was quite the turbulent year for the American populous. The war was coming to a close, and America saw the return of their heroes after a glorious battle. But, there was also a feeling of nervous uncertainty and anxiety regarding the heroes return. The reviewers and reviews of Since You Went Away were very much in tune with this feeling. In the press, critics viewed this film in either of two ways. First, it seen as a triumphant return of Selznick and secondly, the critics thought the movie attempted at a realistic portrayal. An article in Variety Magazine boasted “it’s a box office mop-up” and the article also listed the complete list of about ninety actors involved.

Went Away would be a blockbuster. Selznick spent nearly “$3,000,000 on this film”, (Thomas p. 220) which meant glossy and detailed scenes throughout the film. This was an unusual amount of money for a film from this period, but David Selznick was known in Hollywood for his elaborate budgets. The films length allowed Selznick to allow it to take place over a year. The story begins in January 12, 1943 which is immediately after Mr. Hilton departs for the war. The Hiltons are a middle/upper class family who are now faced with dealing with dealing with the trials and tribulations of everyday life without the support of a male authority figure. A lot of emphasis is placed on the female audience’s familiarity with “the details of day to day living and plenty of humorous sentimental reportage of housekeeping: rationing, the problems of two growing daughters and the business of getting jobs to help the family’s reduced budget.”(Hartung p 374) Selznick increased the original ages of the two daughters so Shirley Temple (Bridget) and Jennifer Jones (Jane) could play the roles and romance could be introduced. Nineteen forty-four was quite the turbulent year for the American populous. The war was coming to a close, and America saw the return of their heroes after a glorious battle. But, there was also a feeling of nervous uncertainty and anxiety regarding the heroes return. The reviewers and reviews of Since You Went Away were very much in tune with this feeling. In the press, critics viewed this film in either of two ways. First, it seen as a triumphant return of Selznick and secondly, the critics thought the movie attempted at a realistic portrayal. An article in Variety Magazine boasted “it’s a box office mop-up” and the article also listed the complete list of about ninety actors involved.

The critic constantly mentioned David Selznick’s name throughout the review and thus, set the tone for the magnitude of this film. Similarly, in a Newsweek article, there was constant enforcement of how much money was spent on this film and how much Selznick made on his last film. This worked as a quality control mechanism for Hollywood and the viewing audience. People knew what to expect when they went out to see a David Selznick film. The second type of review paid particular attention to the “realism” of this film. A review in Time Magazine stated: “this is the most human, factual picture to date”. It mentioned the film dealing with things like the sorrow of death, and the comfort of religion, food shortages, and being away from loved ones. For example, a scene where a telegram is sent to Mrs. Hilton, informing her that her husband is missing in action. This scene takes place after the housekeeper receives the telegram and yells for Mrs. Hilton who was sleeping. Upon reading the letter, Mrs. Hilton insists that there is still hope and he is still alive. The American public at the time of this release, were caught up in these “everyday” feelings and it was apparent that Selznick deal with these issues with as much love and heart as Selznick could fit on-screen. In another review they mentioned that the film is “always authentic, endearing and true to life as death and taxes” (Abel p 13) This “realism” was constantly reinforced with sequences like the scenes in the rehabilitation’s rooms, psychiatrist’s office and recovery wards. In these scenes, the film maker uses lighting to cast shadows in these rooms. This is especially prevalent in the scene where Jane Hilton says good-bye to her boyfriend Billy at the train station. The long shadows are used to show the shadow that is cast over America at this point in history and to enhance this on-screen realism. Indeed, this issue was the case for many Americans and people from other countries as well. Overall, it was the message that appealed to the audience the most and the modern day press agreed with this films message.

But, this wasn’t the absolute case. A famous film critic, at the time was very harsh on this film. He downplayed Selznick’s attempt at portraying a typical American Family. In The Nation, James Agee writes about the home that the Hiltons reside in: “They live in an American home that seven out of ten Americans would sell their souls for”. This review addressed the issue of class, which is the main bone of contention that most of the more recent articles death with. It is quite easy to look back at older films and sneer at them as inferior. But these films from the forties and fifties are cultural products that were apart of the social fabric at this time. One must look at the politics that were in place at the time, and see how that effected a medium such as film. Since You Went Away was shown to the people of America to increase support and motivate people to get involved. It was also shown to troops because it the film was also saying: “they’ll be there when you get back”. (Jarvie Lecture Jan 19) Since You Went Away was one of the first films to deal with the American home front and the issue of the soldiers return. Selznick’s past  experiences led him to understand “not of what Americans were, but what Americans wanted to be.” (Koppes p 157) Today, this film looked upon as a model of how Americans were expected to behave.

experiences led him to understand “not of what Americans were, but what Americans wanted to be.” (Koppes p 157) Today, this film looked upon as a model of how Americans were expected to behave.

This film could be seen as a teaching tool for the average American. Seeing a family such as the “Hiltons” on-screen, pinching from their usual weekly budgets and bringing a extra income- is a lesson to be learned. The Hilton family is thrusted into new situations they might never have dealt with prior to the war. Since this film was projected towards the female market, the film gave a strong message about empowering women. In the period in which this film was made, the climate for gender equality wasn’t really an issue. With all the men off at war, women started to take up male roles and jobs to fill the temporary gap. Jane who wanted a job before her father left, eventually got one as a nurse’s aid. After Mrs. Hilton agrees with Jane, a cut to the capping ceremony where Jane, “with shining face and sun glinting off her white cap, recites the Red Cross pledge.” (Koppes p 157) Bridget is the young eager citizen who can’t do enough for her country. She constantly complains that she is only doing “kid’s stuff” for the war. Anne Hilton is also set up as a model citizen. For example, she is portrayed as unhappy and lonely. Many scenes feature a “slick” Lieutenant Tony Willet making subtle hints for his unquestioning love for Anne. The audience is usually left wondering if Anne will give up hope and marry Tony. Anne sticks it out and her and Tony remain close throughout the troubled war and they stay strictly “friends.” Another point more current literature on this film investigates, is the issue of reality.

A boy with an amputated arm yells to the conductor: “Can’t this train get moving? I’ll miss my pop!” The conductor replies: “Your pop will have a lot better chance if these supply trains get through” This scene is reinforcing a sense of teamwork, and a the American duty to work together. Propaganda aside, did this film bring the real issues to the silver screen? Perhaps, Selznick’s desire for perfection got in the way of the real story of the American home in war time. Paying “too much attention to love scenes, costumes, gestures” (Agee p 137) possibly made the film look too artificial. In order to present the Hilton’s house as a fun and happy home- the Selznick’s portrayal of the Hilton cook (Fidelia) is a little skewed. The Hilton’s were forced to let Fidelia go because Anne could no longer afford to pay her. After the first 30 minutes of the film, the cook has already moved back into the home to work for free. There is also the issue of the Hilton home. This docile is a modest place of an advertising executive which was supposedly a “typical” American home. The home was very elaborate and had plenty of extra space for 2 other house guests. Some of these images that are prevalent in this film are not exactly the same as the average American’s. The scenes mentioned above and many more, presented a classless society which was definitely not the case in nineteen forty-four. Most critics enjoyed this picture. After all these were troubled times and Americans weren’t sure what to think.

It’s safe to say that the movie going audience did want to laugh but they also wanted to cry- and that’s what this film allowed the audience to do. Since You Went Away, also points at many interesting aspects of nineteen forties post-war society. Selznick’s particular attention to style and form brought this film to its highest level. Selznick once said: “Since You Went Away would remain the definitive home-front movies until a realist comes along to show us what life is really like in America during World War II.” I think Clayton Koppes describes the film and David Selznick best when he answers Selznick’s comments about the film: “Yet there lay Selznick’s brilliance. The film triumphed precisely because it was not realistic. With Hollywood’s slickest touch he wove together the sacred and the sentimental symbols of American life and set them n the national shrine: the middle class home.” I believe the film was a bit too long and a lot of scenes should have been omitted. In my opinion, a long movie doesn’t necessarily make a good movie. Nevertheless, it was quite interesting to investigate old films and see the differences in opinion four decades can make.

Sources Cited

Abel. Brian. “Since You Went Away.” Variety July 19, 1944 p13 Agee, James. “Films” The Nation July 29, 1944 p137. Allen, Robert and Gomery, Douglas “Film History – Theory and Practice” New York: N. Award Records 1985. Crowther, Bosley. “Since You Went Away,” A Film of Wartime Domestic Life, With Claudette Colbert and Others, Opens at the Capitol.” New York Times July 21, 1944. Eyman, Giannetti “Flashback – A Brief History of Film” New Jersey: Prentice Hall 1991. Fenster, Mark. “Constructing the image of authorial presence: David O. Selznick and the marketing of since you sent away” Journal of Film and Video 4.1 Spring 1989: p36-55. Fearing, Franklin “Warrior Return: Normal or Neurotic?” Hollywood Quarterly Vol. 1, 1945-1946: p96-107. Hartung, Philip. “The Screen: While You Are Gone, Dear.” The Commonweal August 4, 1944 p374-375. Koppes, Clayton “Hollywood Goes to War” New York: Free Press 1987. p154-162. Newsweek “First GWTW, Now SYWA” July 10, 1944 p85-6. Thomas, Bob. “Selznick” New York: Doubleday & Company, 1970