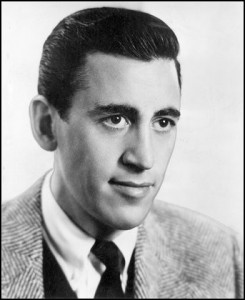

J.D. Salinger’s youth and war experiences influenced his writings. J.D. went through four different schools for education. He then went to World War II. After the war, he had a lot to say, so he wrote down his thoughts. And, he sure had some things to say. Jerome David Salinger came into this world on January 1, 1919. J.D. was short for Jerome David. Jerome David went by J.D. when he was young and he never let go of the name as he got older. J.D. was born in New York City, New York (Ryan 2581).

J.D. Salinger’s parents were Sol and Miriam Salinger(Ryan 2581). His father, Sol Salinger, was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and is said to  have been the son of a rabbi. However, Sol drifted far from orthodox Judaism to become an importer of hams. Sol married a Scotch-Irish lady (French 21). The lady’s name was Marie Jillich. She changed her name to Miriam to fit into her husband’s family (French 21). Jerome David had a roller coaster marriage record. He was allegedly married to a French physician in 1945 and divorced her in 1947 (Ryan 2581). But other sources say that Salinger has never admitted this marriage and the records of the Florida Bureau of Vital Statistics fail to indicate that a divorce was granted in that state in 1947 to Jerome David Salinger (French 26). He then married Claire Douglas on February 17, 1955. Claire Douglas was a Radcliff graduate born in England. In 1955, the two of them settled down in Cornish, New Hampshire, where they raised two children (Unger 552). J.D. divorced Claire Douglas in October 1967 in Newport, New Hampshire (Ryan 2581). In 1932, the time J.D. should have begun high school, he was transferred to a private institution, Manhattan’s McBurney School.

have been the son of a rabbi. However, Sol drifted far from orthodox Judaism to become an importer of hams. Sol married a Scotch-Irish lady (French 21). The lady’s name was Marie Jillich. She changed her name to Miriam to fit into her husband’s family (French 21). Jerome David had a roller coaster marriage record. He was allegedly married to a French physician in 1945 and divorced her in 1947 (Ryan 2581). But other sources say that Salinger has never admitted this marriage and the records of the Florida Bureau of Vital Statistics fail to indicate that a divorce was granted in that state in 1947 to Jerome David Salinger (French 26). He then married Claire Douglas on February 17, 1955. Claire Douglas was a Radcliff graduate born in England. In 1955, the two of them settled down in Cornish, New Hampshire, where they raised two children (Unger 552). J.D. divorced Claire Douglas in October 1967 in Newport, New Hampshire (Ryan 2581). In 1932, the time J.D. should have begun high school, he was transferred to a private institution, Manhattan’s McBurney School.

There, J.D. told the interviewer that he was interested in dramatics; but J.D. reportedly flunked out within a year (French 22). In September 1934, his father enrolled him at Valley Forge Military Academy in Pennsylvania(French 22). In 1935, while attending Valley Forge, J.D. was the literary editor of Crossed Sabers, the Academy Yearbook. Salinger’s grades at Valley Forge were satisfactory. His marks in English varied from 75 to 92. His final grades were: English 88, French 88, German 76, History 79, and Dramatics 88. As recorded in J.D.’s Valley Forge file, his I.Q. was 115.

While such scores as J.D.’s must be treated with caution, this one and another one of 111 that he made when tested in New York are strong evidence that he was slightly above the average in intelligence, but far from the “genius” category. At Valley Forge, Salinger belonged to the Glee Club, the Aviation Club, the French Club, the Non-Commissioned Officer’s Club, and Mask and Spur (a dramatic organization)(French 22). While at Valley Forge, Salinger began writing short stories, working by flashlight under his blankets after official “lights out” (French 23). In June of 1936, J.D. graduated from Valley Forge Military Academy (French #2 15). In 1937, Salinger attended the summer session at New York University. He attended the Washington Square College campus of New York University. There is little documented about J.D.’s attendance at New York University. Shirley Blaney, a high school student, and the only person in the world to ever interview J.D. Salinger, said that it appears unlikely that Salinger attended New York University for two years (French 23).

In 1939, Salinger returned to New York after traveling to vienna and Poland for a year, to enroll in Whit Burnett’s famous course in short-story writing at Columbia University. According to Ernest Havemann, “Burnett was not at first impressed with the quiet boy, who made no comments and was interested primarily in play writing; but Salinger’s first story, “The Young Folks,” which he turned in near the end of the semester, was finished enough to use in Story, edited by Burnett” (French 23). When the war began, Salinger wrote to Colonel Miltion B. Baker, at Valley Forge Military Academy, that he wished to enter the service, but had been classified 1-B due to a slight cardiac condition. J.D. asked what kind of defense work he might do; but it was not long before Selective Services standards were lowered enough, so that he was drafted in 1942 (French 24). In September of 1942, there was a letter announcing that Jerome David was attending the Officers, first Sergeants, and Instructors School of the Signal Corps. So in September of 1942, Salinger was in the war (French #2 15). During the first part of his military service, Salinger corrected papers in a ground school for aviation cadets, probably in Tennessee. While in Tennessee, J.D. was classified with the rank of Staff Sergeant. J.D. was in Tennessee until June 2, 1943 (French 24). At the end of 1943, Salinger was transferred to the Counter-Intelligence Corps. While at the Counter-Intelligence Corps, J.D. was also corresponding with Eugene O’Neill’s daughter Oona, who after J.D. left her, became Mrs. Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood. In 1944, J.D. had additional Counter Intelligence training at Tiverton,

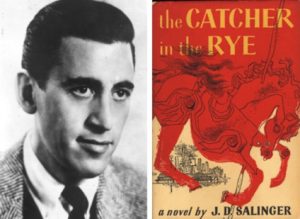

Devonshire, England (French 25). J.D. entered the war when he joined the American Army’s Fourth Division that had landed on Utah  Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944 (French #2 15). Also in 1944, Salinger participated in five campaigns in Europe as special agent responsible for the security of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment. While at the Twelfth Infantry Regiment it is noted that Salinger met Ernest Hemmingway when the author-correspondent visited Salinger’s regiment. It was then that Salinger became disgusted when Hemmingway shot the head off a chicken to demonstrate the merits of a German Luger (French #2 16). The Catcher in the Rye is a deceptively simple, enormously rich book whose sources of appeal run deep and complexly varied veins (Unger 553). As of 1966, Catcher in the Rye had sold over 1.5 million copies in the United States (Vertical/Biography 7). As of 1966, Franny and Zooey shot to second place on the best seller list (Vertical/Biography 7). This book was two stories. “Franny” was first published in the New Yorker, January 25, 1955. “Zooey” was first published also in the New Yorker, on May 4, 1957 (Ryan 2581). The book Hapsworth 16, 1924 was published under the circumstances in which Salinger had agreed to publish, “at all bespeak a secretiveness verging on misanthropy”(Vertical/Literature 51). The company that published the story was an entirely obscure company, Orchises Press in Alexandria, Virginia. In this novella, “Salinger reintroduces us to the illustrious, eccentric, and Andst-ridden Glass family” (Vertical/Literature 51), with its parents and seven children, once famous as radio whiz kids (Vertical/Literature 51). The family’s first appearance was in “A Perfect Day for BananaFish.” In this book, the main character’s brother Buddy, who is younger by two years and was with him at the camp, purports to have just received the letter, 41 years after it was written, in a package from their parents (Vertical/Literature 51). J.D. Salinger’s youth and war experiences influenced his writings. Those two items alone were enough to say that Jerome David Salinger led an interesting life. And the third item, his writings, was something that he had many of. But because of his war experience, maybe he was left scared, causing him to become a loner. Only one person has ever interviewed Salinger.

Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944 (French #2 15). Also in 1944, Salinger participated in five campaigns in Europe as special agent responsible for the security of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment. While at the Twelfth Infantry Regiment it is noted that Salinger met Ernest Hemmingway when the author-correspondent visited Salinger’s regiment. It was then that Salinger became disgusted when Hemmingway shot the head off a chicken to demonstrate the merits of a German Luger (French #2 16). The Catcher in the Rye is a deceptively simple, enormously rich book whose sources of appeal run deep and complexly varied veins (Unger 553). As of 1966, Catcher in the Rye had sold over 1.5 million copies in the United States (Vertical/Biography 7). As of 1966, Franny and Zooey shot to second place on the best seller list (Vertical/Biography 7). This book was two stories. “Franny” was first published in the New Yorker, January 25, 1955. “Zooey” was first published also in the New Yorker, on May 4, 1957 (Ryan 2581). The book Hapsworth 16, 1924 was published under the circumstances in which Salinger had agreed to publish, “at all bespeak a secretiveness verging on misanthropy”(Vertical/Literature 51). The company that published the story was an entirely obscure company, Orchises Press in Alexandria, Virginia. In this novella, “Salinger reintroduces us to the illustrious, eccentric, and Andst-ridden Glass family” (Vertical/Literature 51), with its parents and seven children, once famous as radio whiz kids (Vertical/Literature 51). The family’s first appearance was in “A Perfect Day for BananaFish.” In this book, the main character’s brother Buddy, who is younger by two years and was with him at the camp, purports to have just received the letter, 41 years after it was written, in a package from their parents (Vertical/Literature 51). J.D. Salinger’s youth and war experiences influenced his writings. Those two items alone were enough to say that Jerome David Salinger led an interesting life. And the third item, his writings, was something that he had many of. But because of his war experience, maybe he was left scared, causing him to become a loner. Only one person has ever interviewed Salinger.

good read!

Darn, I really wanted to see the picture of Larry David. Thanks, Alice.

The wrong gallery was imported for this article; this occurs on rare occasion. The problem has been corrected and thank you very much for bringing it to our attention Alice.

Why do you have a picture of Larry David in an article about JD Salinger? And if there is some good reason to include it, why not label it “Larry David” instead of putting Salinger’s name on it? It gives the impression that you Googled it and stole it without properly citing it and without even realizing it wasn’t even the photo you’d really wanted.