Aeschylus’ use of darkness and light as a consistent image in the Oresteia depicts a progression from evil to goodness, disorder to order. In the Oresteia, there exists a situation among mortals which has gotten out of control; a cycle of death has arisen in the house of Atreus. There also exists a divine disorder within the story which, as the situation of the mortals, must be brought to resolution: the Furies, an older generation of gods, are in conflict with the younger Olympian gods because they have been refused their ancient right to avenge murders between members of the same family.

The Oresteia presents two parallel conflicts, both of which must be resolved if harmony is ever to be desired again. As one can expect, these conflicts eventually do find their resolutions, and the images of darkness and light accompany this progression, thereby emphasizing the movement from evil to good.

The use of darkness imagery first emerges in the Agamemnon. In this first play of the trilogy, the cycle of death which began with the murder and consumption of Thyestes’ children continues with Clytaemestra’s murder of Agamemnon and Cassandra.

The darkness which is present at the beginning of the story is further magnified by the death of Agamemnon. This is illustrated when Clytaemestra says, “Thus he [Agamemnon] went down, and the life struggled out of him, and as he died he spattered me with the dark red and violent driven rain of bitter savored blood” (lines 1388-1390).

Clytaemestra has evilly and maliciously murdered her own husband; thus the image of the dark blood. The darkness is representative of the evil which has permeated the house of Atreus, and which has persisted with this latest gruesome act of murder.

Because darkness results from the death of Agamemnon, Aeschylus clearly illustrates that this murder was nothing but pure evil. As long as this type of evil continues to be practiced in the house of Atreus, darkness will continue to emerge. The Oresteia has not yet seen the light.

The beginning of the progression from darkness to light can initially be seen in the second play of the trilogy, The Libation Bearers. Orestes is the embodiment of this light, a beacon signaling a possible end in the evil that has infected the house of Atreus. It is true that Orestes, in revenge for Agamemnon, kills his mother Clytaemestra.

Yet the darkness that is expected from such a murder, a matricide, is negated by one of the main reasons that Orestes commits the murder: his fear of the wrath of Apollo, who has ordered him to commit the deadly act. Aeschylus provides Orestes with a justification for his action in the form of the oracle from Apollo. For not only does Orestes’ murder of his mother fail to differ greatly from Clytaemestra’s murder of Agamemnon, but it can in fact be seen as a worse crime because of the blood ties.

Therefore, in order to convincingly prove his assertion that Orestes is justified in killing his mother, Aeschylus must include the order from Apollo, who by no mere coincidence is the god of light. With the divine support of the light god on his side, Orestes is the beginning of the progressive illumination towards goodness and order in the Oresteia.

Another example of Orestes’ introduction of light into a story of darkness occurs later in The Libation Bearers. The chorus is describing the dream that Clytaemestra has had of giving birth to a snake, which represents Orestes.

The chorus sings of Clytaemestra’s fear as she awakens from the nightmare: “She woke screaming out of her sleep, shaky with fear, as torches kindled all about the house, out of the blind dark that had been on them” (lines 535-537).

Aeschylus describes the house of Clytaemestra, the rightful house of Atreus and the Atridae, as dark; this darkness has been caused by none other than her own murderous deeds. She has dreamt of the coming of her son Orestes to avenge his father and the torches that light up the house signal this coming. Clearly, Orestes is the man who will restore light to the house of Atreus.

Orestes is looked upon by those characters sympathetic to his plight (namely Electra and the chorus of The Libation Bearers) as the light which will bring an end to the evil in the house of Atreus. Soon after Orestes reveals his identity to his sister, he proclaims that he will avenge his father’s murder.

The chorus, who represent the subjects of the late Agamemnon, express their gratitude for Orestes’ decision when they say, “But when strength came back hope lifted me again, and the sorrow was gone and the light was on me” (lines 415-417). Orestes’ arrival and his resolution to make his mother pay for her crimes illuminates the darkness which Clytaemestra has brought upon the royal house; the chorus, in proclaiming that the light is on them, recognizes that Orestes is the man who will achieve this illumination.

Electra also recognizes that Orestes will bring good to an evil situation: “O bright beloved presence, you bring back four lives to me” (lines 238-239). Orestes’ presence brightens the dark, gloomy state of mind of Electra just as it brightens the dark, gloomy situation in the house of Atreus.

Following the murder of Clytaemestra and Aegisthus at the hands of Orestes, light is finally restored to the conflict within the mortal house of Atreus. Orestes has fulfilled the oracle imposed upon him by Apollo, and the darkness, the evil of Clytaemestra, has been defeated. In reference to this defeat, the chorus proclaims, “Light is here to behold.

The big hit that held our house is taken away” (lines 961-962). The disorder and darkness that had reigned in the house of Atreus exist no longer; Orestes has given his family illumination. The evil darkness has been overcome by the good light.

Another way in which Aeschylus manifests the imagery of light and darkness is through the conflict between the Olympic and Chthonic gods. The Olympic gods are represented in the Oresteia by Apollo and Athene. Aeschylus ties together the ideas of justice and reason, Athene’s domain, with the idea of light, of which Apollo is god.

By contrast, the black-clad Chthonic gods, the Furies, tie together the idea of darkness with the idea of bloody revenge, which is their area of specialization. In the Eumenides, Pythia says of the Furies, “They are black and utterly repulsive, and they snore with breath that drives one back” (lines 52-53). The contrast between the two different races of gods sets up Aeschylus’ second progression from darkness to light in the Oresteia.

The Furies are at first incapable of treating Orestes with the justice that he deserves. They do not take into account the circumstances under which Orestes killed his mother, specifically the pressure which he had received from Apollo. Therefore, the Furies are at first enraged that Athene allows Orestes to escape their dark and bloody vengeance.

Eventually, however, the Furies’ hate begins to subside and they accept the arbitration of Athene, who offers them land and honor in Athens. This acceptance marks the beginning of their movement from darkness to light. They embrace the just attitude of the Olympic gods, Apollo and Athene, progressing from a doctrine of bloody revenge to one of reason and justice. The light images emerge along with this progression, and the Furies proclaim near the end of the Eumenides: “So with forecast of good I speak this prayer for them [the citizens of Athens] that the sun’s bright magnificence shall break out wave on wave of all the happiness life can give, across their land” (lines 921-925).

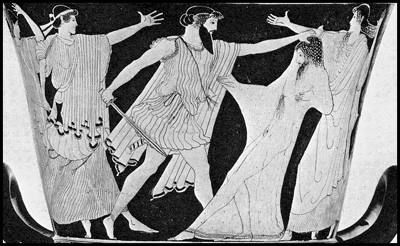

The Chthonic gods have given up their dark ways and have called for light. This light image is also manifested in the garments that the Furies change into at the end of the Eumenides: where they had previously worn black robes, they now wear bright crimson robes. Now calling themselves the Eumenides, or Benevolent Ones, these gods have progressed from symbols of evil darkness into symbols of bright goodness.

In his trilogy, the Oresteia, Aeschylus’ use of darkness and light imagery coincides with his progression of themes. Orestes, who represents light, brings an end to the vicious cycle of dark death continued by Clytaemestra. He illuminates the dark evil in the house of Atreus.

Likewise, Athene and Apollo bring the Furies out of their dark, blood-lusting ways and into an order of justice and reason, transforming them into the brightly clad Benevolent Ones. In the end, goodness prevails over evil just as light conquers darkness. Aeschylus effectively makes use of his images to emphasize this movement.