Hamlet is the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays for theater audiences and readers. It has been acted live in countries throughout the world and has been translated into every language.

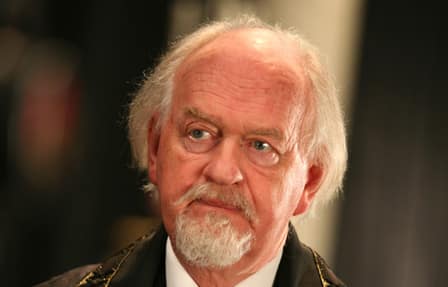

Polonius is one of the major characters in Hamlet, his role in the play is of great interest to scholars. Parts of Hamlet present Polonius as a fool, whose love of his own voice leads to his constant babbling.

Scholars have been analyzing the character of Polonius for centuries, and his role in Hamlet will continue to be analyzed for centuries to come. Scholars believe that Shakespeare created Polonius as a fool because of his foolish dialogue throughout the play.

Polonius granted Laertes permission to go back to school in France. While saying good-bye in his chambers, Polonius tells his son:

“Beware Of entrance to a quarrel, but, being in, Bear’t that th’ opposed may beware of thee. Give every man they ear, but few thy voice. Take each man’s censure, but reserve they judgment. Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy, But not expressed in fancy (rich, not gaudy) For the apparel oft proclaims the man, And they in France of the best rank and station (Are) of a most select and generous chief in that. Neither a borrower or a lender (be,) For (loan) oft loses both itself and friend, And borrowing (dulls the) edge of husbandry. This above all: to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man.” (1. 3. 71-87)

The advice that Polonius gives to Laertes is simple and sounds foolish being told to a person of Laertes’ age. Martin Orkin comments on the nature of Polonius’ speech:

“Shakespeare’s first audience would recognize in Polonius’ predilection for such commonplace expressions of worldly wisdom a mind that runs along conventional tracks, sticking only to what is practically useful in terms of worldly self-advancement” (Orkin 179).

Polonius gives Laertes simple advice, to keep his thoughts to himself and to never lend or borrow money. While this advice is simple, when looked at in full context his advice to his son is all about self-advancement. Polonius will go to all extremes to protect his reputation.

Grebanier states on the foolishness of Polonius’ speech: “Such guidance will do for those who wish to make the world their prey, but it is dignified by no humanity. Who can live humanly without ever borrowing or lending? Is one to turn his back on his best friend in an hour of need?” (Grebanier 285).

Scholars believe that the advice Polonius gives to his son is simple, and when looked at in full context, is foolish and selfish. After Laertes returns to Paris, Polonius send his servant Reynaldo to Paris to spy on Laertes and question his acquaintances. Polonius says to Reynaldo:

At “closes in the consequence”-ay, marry- He closes thus: “I know the gentleman. I saw him yesterday,” or “th’ other day” (Or then, or then, with such or such), “and as you say, There was he gaming, there (o’ertook) in’s rouse, There falling out at tennis”, or perchance “I saw him enter such a house of sale”- Videlicet, a brothel- or so forth. See you now Your bait of falsehood take this carp of truth; And thus do we of wisdom and of reach, With windlasses and with assays of bias, By indirections find directions out. (2. 1. 61-75)

By spying on Laertes, Polonius is showing the audience and the reader, that he does not trust him. After giving Laertes a speech on how to behave, Polonius still feels that he has to spy on his son. Joan Hartwig comments on Polonius’ plan to spy on his son: “A Machiavellian schemer who takes his plotting to absurd proportions, Polonius pursues ‘indirection’ for its own sake.

His efforts to discover Laertes’ reputation in Paris assume that Laertes will not follow his earlier advice; thus, the later words become a comic reduction of his previous sermon to his son” (Hartwig 218). Another reason for Polonius’ foolishness is that Polonius is convinced, and tries to convince others, that the reason for Hamlet’s madness is his love for Ophelia. He tells Ophelia:

“Come, go with me. I will go seek the king. This is the very ecstasy love, Whose violent property fordoes itself And leads the will to desperate undertakings As oft as any passions under heaven That does afflict out natures. I am sorry. What, have you given him any hard words of late? (2. 1. 113-119.”

After hearing of Hamlet’s madness, he immediately reaches a conclusion and believes, throughout the play, that he is correct. He does not consider other possibilities and foolishly jumps to the conclusion that Hamlet is mad for Ophelia’s love. R.S.

White believes that Polonius should have considered other options for Hamlet’s madness: “But when saying that it is simply Ophelia’s rejection that has made Hamlet mad, he is ignorant of the predisposed mental state of the young man caused by his mother’s remarriage, the recent encounter with the ghost and the whole repressive machinery of Denmark’s social and political life” (White 67).

Polonius foolishly believes that he knows what underlies Hamlet’s madness; while Hamlet, and the audience, knows that he is wrong. Polonius continues to demonstrate his foolishness by babbling and losing his train of thought when speaking to the King and Queen. Polonius is convinced that Hamlet is mad in love for Ophelia and says:

My liege, and madam, to expostulate What majesty should be, what duty is, Why day is day, night night, and time is time Were nothing but to waste night, day, and time. Therefore, (since) brevity is the soul of wit, and tediousness the limbs and outward flourishes, I will be brief. Your noble son is mad. ‘Mad’ call I it, for, to define true madness, What is ‘t but to be nothing else but mad? But let that go. (2. 2. 93-102).

He says that he will be brief, but continues to babble. The Queen responds to his statement by saying “More matter with less art” (2. 2. 103). The Queen acknowledges Polonius’ constant babbling and wants him to get quickly to the point.

Grebanier comments on the character of Polonius: “Nothing is left of his ability and shrewdness but a few tags, a few catch-phrases, to which, even when they do express some grains of truth, he pays scant heed in his own demeanor. It is he, for example, who utters the celebrated: ‘brevity is the soul of wit’ (2. 2. 90) -a profound truth; but no character in Shakespeare is so long winded as Polonius” (Grebanier 283).

Polonius continues to complicate a simple statement and is viewed as a babbling fool by scholars. Throughout the play, Hamlet continues to insult Polonius and make him look foolish to the audience. Hamlet tells Polonius: “You are a fishmonger” (2. 2. 190).

According to Leo Kirschbaum: “A fishmonger is a barrel, one who employs a prostitute for his business. Hamlet is obliquely telling the old councilor that he is using his own daughter for evil ends” (Kirschbaum 86). After Hamlet insults Polonius and Ophelia, Polonius still refuses to give up this theory that Hamlet is madly in love.

Martin Dodsworth comments on the reaction of Polonius after Hamlet insults him: “Polonius accepts the bad treatment sent out to him as that of a man who is out of his mind: ‘How say you by that? Still harping on my daughter. He is far gone’” (Dodsworth 100).

The Shakespearean audience viewed Hamlet as the protagonist of the play, and some scholars believe that Polonius served as his perfect foil. Bert States comments, “Polonius is not only the perfect foil for Hamlet’s wit (since irony is the mortal enemy of the order prone mind), but a shadow of Hamlet as well.

Indeed, Polonius literally shadows Hamlet, or tails him and in shadowing him falls into a thematic parody of his own habits” (States 116). Thus, Polonius’ role in the play as Hamlet’s foil would be the role of the fool. The last time Polonius appears in Hamlet is when he hides behind a curtain in Gertrude’s room, to hear Hamlet’s conversation with his mother. Hamlet frightens Gertrude and she cries for help.

Immediately after, Polonius foolishly echoes her cry and is stabbed by Hamlet, thinking it is Claudius. Hamlet, realizing he has killed Polonius says: Thou wretched, rash, intruding fool, farewell. I took thee for my better. (3. 4. 38-39)

Elizabeth Oakes comments on this scene, “Although Polonius is not in motley, Hamlet calls him a fool often enough, although nowhere more significantly than in the closet scene after the murder” (Oakes 106). Hamlet ruthlessly calls Polonius a fool, and his opinion, as the play’s protagonist, would greatly influence an Elizabethan audience’s view of Polonius.

When Gertrude tells Claudius of Polonius’ death, Claudius responds by saying: O heavy deed! It had been so with us, had we been there. (4. 1. 13-14) Claudius knows that Polonius has been killed in his place. Oakes comments on Polonius’ role a the plays fool: “He is suited for this role because of his incarnation of the fool, the one traditionally chosen as a substitute for the king in ritual” (Oakes 106).

Scholars view Polonius as a character mocked throughout the play and the nature of his death, as the Kings substitute, lead scholars to view him as a fool.

In conclusion, Shakespeare created Polonius as a very unique and complex character. Scholars argue and will continue to argue over the reasons for Polonius’ foolishness.

Throughout the play Polonius tends to act foolish thinking that he knows the reason for Hamlet’s madness, while the audience knows that he is wrong. Shakespeare created Polonius as a controversial character and only he will ever know why Polonius was created so foolish.

Works Cited

- Grebanier, Bernard. The Heart of Hamlet. New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell Co, 1960. Hartwig, Joan. “Parodic Polonius”. Texas Studies in Literature and Language: vol. 13, 1971.

- Kirschbaum, Leo. Character and Characterization in Shakespeare. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1962.

- Oakes, Elizabeth. “Polonius, the Man behind the Arras: A Jungian Study.” New Essays on Hamlet. New York: AMS Press, 1994.

- Orkin, Martin. “Hamlet and the Security of the South African State.” Critical Essays on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. New York: G.K. Hall and Co, 1995.

- Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New York: Washington Square Press published by Pocket Books, 1992.

- States, Bert O. Hamlet and the Concept of Character. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 1992.

good lord. This was extremely hard to follow. Why use long quotes without quotation marks?

Hi Eric, we have re formatted the article as per your suggestion. We hope it is easier to read.

This information was very useful!