CHILDHOOD

Born in Richland Center, in southwestern Wisconsin, on June 8, 1867 (Sometimes reported as 1869), Frank Lincoln Wright (Changed by himself to Frank Lloyd Wright) was raised in the influence of a welsh heritage. The Lloyd-Jones family, his mother’s side of the family, had a great influence on Mr. Wright throughout his life. The family was Unitary in faith and lived close to each other. Major aspects within the Lloyd-Jones family included education, religion, and nature. Wright’s family spent many evenings listening to William Lincoln Wright read the works of Emerson, Thoreau, and Blake out loud.

Also, his aunts Nell and Jane opened a school of their own, pressing the philosophies of German educator, Froebel. Wright was brought up in a comfortable but certainly not warm household. His father, William Carey Wright, who worked as a preacher and a musician, moved from job to job, dragging his family across the United States. His parents divorced when Wright was still young. His mother Anna (Lloyd-Jones) Wright, relied heavily on her many brothers, sisters and uncles, and was intellectually guided by his aunts and his mother.

Before her son was born, Anna Wright had decided that her son was going to be a great architect. Using Froebel’s geometric blocks to entertain and educate her son, Mrs. Wright must have struck the genius her son possessed. Use of the imagination was encouraged and Wright was given a free run of the playroom filled with paste, paper, and cardboard.

On the door were the words, SANCTUM SANCTORUM (Latin for: place of inviolable privacy). Mr. Wright was seen as a dreamy and sensitive child, and cases of him running away while working on the farmlands with some uncles is noted. This pattern of running away continued throughout his lifetime.

WRIGHT’S FIRST BREAK

In 1887, at the age of twenty, Frank Lloyd Wright moved to Chicago. During the late nineteenth century, Chicago was a booming, crazy place. With an education in Engineering from the University of Wisconsin, Wright found a job as a draftsman in a Chicago architectural firm. During this short time with the firm of J. Lyman Silsbee, Wright started on his first project, the “Hillside Home” for his aunts, Nell and Jane. Impatiently moving forward, Wright got a job at one of the best known firms in Chicago at the time, Adler and Sullivan. Sullivan was to become Wright’s most significant mentor.

LOUIS SULLIVAN: LIEBER MEISTER

Wright Referred to Sullivan as “Lieber Meister” (beloved master). He admired his talent for ornamentation and his skill of drawing intricate plans and designs. Wright picked up on his ways of Sullivan and soon became ahead of Alder in importance within the firm. Wright’s relationship between himself and his employer caused great amounts of tension between Wright and his fellow draftsmen, and as well as in-between Sullivan and Adler.

Wright was assigned the residential contracts of the firm. His work soon greatened as he accepted jobs outside of the firm. When Sullivan found out about this in 1893, he called Wright on a breach of contract. Rather than drop the “night jobs”, Wright walked out of the firm. When Wright left the company, Sullivan’s quantity of contracts declined quickly. Sullivan soon ran into economic troubles and his international reputation dwindled by 1920. Sullivan was soon regarded as worthless to the architectural world. He resorted to alcoholism and died in 1924 without regaining the glory of what was held in their early years of Chicago.

LIFE AFTER THE FIRM

Wright quickly built up a practice in residential architecture. At one point in his career, Wright would produce 135 buildings in ten years. Wright took a different approach to architecture by designing the furniture, light fixtures, and other things in the structures he made. He developed a unique type of architecture known as the “Prairie” style. Dominated by the horizontal line, the style would make-up the type of buildings designed in the 1900-1913 era of his career. Wright had two other distinctive styles and a period for each one of them, one being the Textile block (1917-1924) and the other the Usonian (1936-1959).

In 1909 Wright took off for Europe, once again leaving a stable life, with six children, a wife, and a well-established business. He traveled to Europe to seek greater fame and recognition. Wright did not stay long in Europe. He left in 1910 for Chicago and Wisconsin to start construction of his second home, Taliesin in 1911. In the year 1913 he got a contract for midway gardens in downtown Chicago. Today is only the drawings. In 1914 disaster struck Wright’s life, on one fateful day, when Taliesin was completed, his mistress, two children and four of Wright’s leading workmen were murdered by a crazed servant. Talesin was also burned to the ground. Wright soon left to Japan.

WRIGHT’S ACCOMPLISHMENTS IN LIFE

By the time Frank Lloyd Wright died in 1959, he had produced architecture for more than seventy years. Wright has changed many styles and set new standards. His Organic approach has put influenced many drafters of today. In the design of the house, he would use materials to blend the house into the setting. He manipulated stone, brick, glass, wood, stucco, concrete, and copper in ways that had never been done before.

There are many amazing buildings designed by him. The amount seems almost uncountable. The Robie house is considered to be a masterpiece of Wright’s career. Made of a few different materials, the house was intended by Wright to have a “homey” or a feeling of unity. The light fixtures and other items were built into the house to keep the unity effect alive. The house was designed and built between 1906 and 1910, the house is located in Chicago. The building was commissioned by Frederick C. Robie, a 30-year-old engineer at the time he approached Wright.

The house, in my opinion, shows the exact definition of the “Prairie” style. The way that it’s built on a narrow city lot and the way it’s horizontal lines are, show the short, flat look of that style. The Imperial Hotel provided Wright with an architectural as well as an engineering challenge. The hotel was finished in 1922 and was criticized for its aesthetic design, but when it survived the 1923 earthquake that left Tokyo in shambles, it was praised. Wright designed a “floating foundation” for the building. The simpleness and horizontal line of his prairie style fit in the culture perfectly, fitting in to their style of architecture.

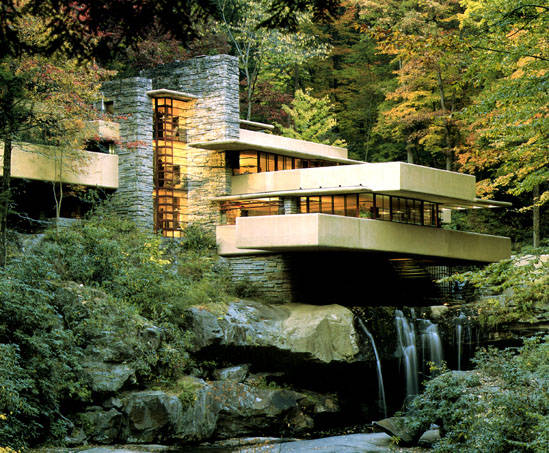

Wright’s trait of using natural materials was also common to the Japanese culture. Fallingwater was another one of Mr. Wright’s masterpieces it also had the exact definition of organic architecture. Wright utilized mostly concrete and stone to create his masterpiece the concrete gives this house a smooth look. The cantilevers make the ledges appear to be self-supporting. The different layers made the building look like a waterfall. Wright built the house around existing trees. He also made the chimney around an already existing boulder. Fallingwater is an amazing house, the rooms and ledges are all very different than the traditional boxy houses of Wright’s time. Fallingwater seems to sprout from its surroundings almost like a plant.

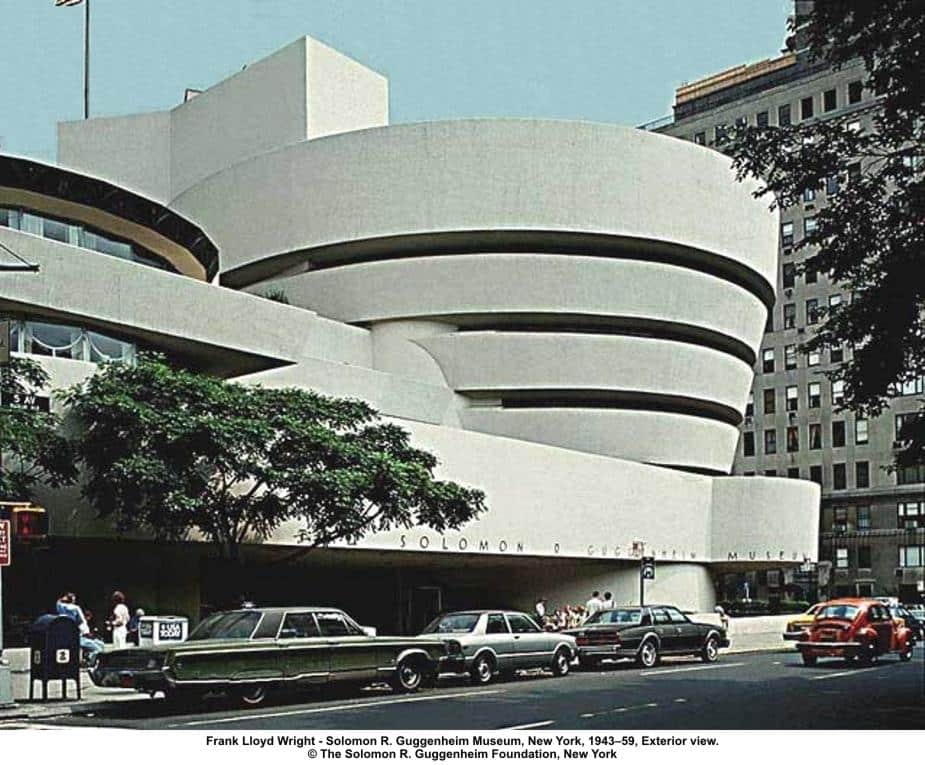

The Guggenheim Museum has been considered Wright’s last great feats. Sadly but true, the museum was opened shortly after his death. The considerable skylight provides light for the entire museum. The spiral/snail shell design seems to grow out of the ground. The design allows people to see the art in a continuous manner. The viewers are intended to take an elevator to the top and walk all the way down viewing the exhibits. Wright never retired; he died on April 9, 1959 at the age of ninety-two in Arizona. He was interred at the graveyard at Unity Chapel (which was considered to be his first building) at Taliesin in Wisconsin. In 1985, Olgivanna Wright passed away and one of her wishes was to have Frank Lloyd Wright’s remains cremated and the ashes put next to hers at Taliesin West, after much controversy this was done. The epitaph at his Wisconsin grave site reads: “Love of an idea is the love of god”.