Class is an obsession that has been prevalent throughout the history of British comedy. In order to be able to fully appreciate the wit and humor of a sophisticated comedy, one must usually have an in-depth knowledge of culture, a pastime usually reserved for the privileged strata of society.

Because class is such an ubiquitous topic throughout British comedy, it is possible to argue that class does dominate the comic form of The History Boys in a way that reflects Bennett’s own experiences throughout his education.

When writing about his ‘Finals at Oxford’[1], Bennett states that he cheated, just as he cheated in his entrance examination, although ‘nobody else would have called it cheating…But it has always seemed so to me. False pretences, anyway.’[2]

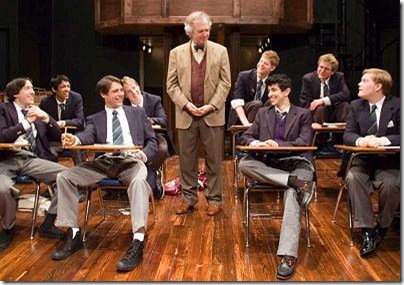

Bennett’s exploration of the class is inevitably comic due to his use of stereotypes, a device first used in Greek New Comedy. Stereotypes are used throughout the play to represent characters within the education system, the best two examples being Rudge and the Headmaster. We are first introduced to Rudge when Hector comments on his pupil’s A Level results with ‘And Rudge too. Remarkable.’

The introduction of the boys taking place during a discussion about their A Level results is interesting as it encourages the audience to form an assumption about each boy based on Hector’s congratulatory speech. Because Rudge’s result is not met with approval but surprise, the audience immediately begins to form a perception of Rudge as one that is perhaps intellectually inferior to the rest of his peers.

Through his introduction to Rudge and his lack of involvement and dialogue in the play, Bennett is, therefore, able to present him as a stereotypical working-class character that is seemingly unintelligent, dull, and overall of no significant merit. He also excels at sport, a pursuit typically seen as one that requires little mental prowess and therefore inferior to academically rigorous subjects.

Humour is created as a result of the irony of Rudge’s immediate acceptance into Oxford, although alternatively one can argue that his acceptance was due to his lack of class standing rather than intelligence, an interpretation that is supported by Rudge’s explanation that ‘they said I was just the kind of candidate they were looking for. College servant’s son, now an undergraduate, evidence of how far they had come’. On the contrary, the Headmaster is described by Mrs Lintott as ‘The chief enemy of culture in any school’.

His obsession with league tables and ranking is curious as in the context of The History Boys, league tables based on results are an anachronism as they were introduced by Margaret Thatcher – ‘The Thatcherite education reform included a national curriculum that would standardize content throughout the nation, making possible national examinations that would provide “league tables” on student performance’[3].

Arguably, Bennett is using this anachronism to argue that league tables have no places in education, as argued by Rachael McIntyre ‘perhaps Bennett is criticising an education system that recognises and rewards the talents of the ‘flashy’ students but fails to acknowledge that practical, hard-working ‘dull and ordinary boys’ are of equal merit’[4], which suggests to the audience that the Headmaster is the least educated (both culturally and academically) out of the faculty and student body alike.

He is a two-dimensional character that does not develop as the act progresses; he is a caricature of the stereotypical headmaster that is driven not by his students’ personal development but simply by league tables and elitism. In this context, much of the humour in terms of the headmaster is created due to his elitist views regarding university (‘Might get in at Loughborough in a bad year‘), contrasted to his own academic history- ‘I went to Hull‘. Stereotypically, Loughborough is associated with sports and other less rigorous academic subjects whereas Hull is a by-word for a lack of culture, the antithesis of Oxford and Cambridge.

The headmaster’s caricature can also be compared to that of Commedia dell’arte’s ‘Il Capitano’, the man that constantly talks and brags yet does not accomplish anything. Despite his attempt to appear sophisticated and elite, a personal aim that perhaps reflects upon his insistence that his school rises up the league tables, he can hardly claim to be cultured or to have the understanding necessary to command his faculty on how to teach.

Intelligence is a characteristic which the English seem to link intrinsically to class, hence why displays of pretentiousness and false impressions of innovation are used frequently in an attempt to make one seem more sophisticated and well-educated. To be intelligent suggests that one is able to work in a respected profession, such as a teacher, doctor or lawyer.

As a result of this association with respectability, intelligence is subsequently often associated with the class too. It is therefore highly amusing when Rudge, who is presented as the least impressive of all the boys, manages to outwit Hector at his game by taking advantage of his knowledge of current culture rather than trying to find an obscure, classical piece of work – “It’s famous, you ignorant little tarts”.

Through this, he demonstrates that he is more mature than the rest of the boys and shows that one does not need to be ostentatious in order to succeed, a fact proven by his immediate admission to Oxford. Rudge’s staunch refusal to subscribe to one ideology shows that he is able to think for himself (“Rudge incorporates many of the teachers’ own character traits: Irwin’s expediency, Mrs Lintott’s facts and, in his own way, he is a non-conformist like Hector, while still recognising the benefits of exam success like the Headmaster.”[5]), an action which is associated with intelligence and therefore with class.

On the contrary, Dakin’s desire to impress Irwin leads him to unwittingly embarrass himself due to his mispronunciation of Nietzsche as ‘Kneeshaw‘. Dakin states that “he let me call him Kneeshaw. He’ll think I’m a right fool”, which suggests to the audience that perhaps Irwin did not correct Dakin out of contempt for his mistake. An educated audience will find Dakin’s conversation with Scripps (“I’ve been reading this book by Kneeshaw”) due to the dramatic irony of the audience knowing that Dakin has mispronounced Nietzsche’s name in front of a teacher whose attention he clearly wants -“I don’t understand it. I have never wanted to please anybody the way I do him.”

Alternatively, it could be argued that Irwin did not correct Dakin because he may have assumed that Dakin was simply following in his footsteps and not conforming to what history accepts as fact. Irwin’s iconoclastic tendencies are fully revealed when he ruthlessly dehumanizes the human suffering of World War Two under Hitler in order to provide an alternative answer to condemning “the camps outright as an unprecedented horror”.

His attempts to find alternative conclusions in order to be hailed as a great historian ultimately lead him to dismiss historical evidence and facts, as explained by Scripps “When Irwin became well known as a historian. It was for finding his way to the wrong end of see-saws, settling on some hitherto unquestioned historical assumption then proving the opposite.” His attempt to prove that “those who had been genuinely caught napping by the attack on Pearl Harbour were the Japanese and that the real culprit was President Roosevelt” equally demonstrates how far he has strayed from the truth, creating humour through the ridiculousness of his theories.

An alternative issue that could be described as dominating the comic form through comic conflict is the ongoing debate about pedagogical ideology. Bennett portrays Irwin as an immoral character in the very first scene of the play by bringing to light his opinion that “the loss of liberty is the price we pay for freedom”, a belief that the audience later finds out is the product of his inherent ability to ignore the well-known, banal truth and to instead think of a different perspective, regardless of its relevance.

Irwin’s belief that “paradox works well and mists up the windows” converts directly to his work ethos as a teacher and it is inevitable that the students will eventually yield to his opinions on education. This immediate reference to a controversial political debate on what is essentially a way to ‘spare’ people from their liberty so that they are free from becoming victims of abuse or attack alludes to Greek Old Comedy.

Irwin’s ability to shamelessly ask Scripps “what has that (truth) got to do with it?” juxtaposed with his addressing the MPs suggests a criticism of the Government, a feature that was prominent throughout Old Comedy. Perhaps there is a bitter irony in Irwin’s role in the government due to his tendency to overlook facts, leading to humor being created out of it.

In conclusion, The History Boys is an arguably class-related play as it explores education and the social stereotypes which are associated with where one studied at. Despite the modernity of our current age, state schools are still seen for the working class and lower echelons of society, with positions in the more coveted grammar and public schools becoming accessible based on intelligence and arguably the potential to transcend their class.

Although Bennett explores various conflicting pedagogical ideals and contrasts Hector’s idealist permanent (yet not immediately relevant) form of education to Irwin’s more shallow and strictly for examinations style of education, the humor that is created from this contrast is will be amusing to the audience due to perceived class stereotypes.

Bibliography

Bennett, Alan: The History Boys

Reitan, A. Earl: Wrapping up the Thatcherite Revolution

McIntyre, Rachel: The History Boys: A Dramatic Counterpoint

[1]Bennett, vii

[2]Bennett, vii

[3]Reitan, 227

[4]McIntyre, 37

[5]McIntyre, 39