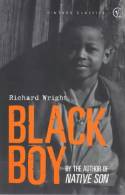

Black Boy, an autobiography by Richard Wright, is an account of a young African-American boy’s thoughts and outlooks on life in the  South while growing up. The novel is 288 pages, and was published by Harper and Row Publishers in (c)1996. The main subject, Richard Wright, who was born in 1908, opens the book with a description of himself as a four-year-old in Natchez, Mississippi, and his family’s later move to Memphis. In addition it describes his early rebellion against parental authority and his unsupervised life on the streets while his mother is at work. His family lives in poverty and faces constant hunger. As a result his family lives with his strict grandmother, a fervently religious woman. In spite of his frequent punishment and beatings, Wright remembers the pleasures of rural life.

South while growing up. The novel is 288 pages, and was published by Harper and Row Publishers in (c)1996. The main subject, Richard Wright, who was born in 1908, opens the book with a description of himself as a four-year-old in Natchez, Mississippi, and his family’s later move to Memphis. In addition it describes his early rebellion against parental authority and his unsupervised life on the streets while his mother is at work. His family lives in poverty and faces constant hunger. As a result his family lives with his strict grandmother, a fervently religious woman. In spite of his frequent punishment and beatings, Wright remembers the pleasures of rural life.

Richard then describes his family’s move to Memphis in 1914. Though not always successful, Richard’s rebellious nature pervades the novel. This is best illustrated by his rebellion against his father. He resents his father’s the need for quiet during the day, when his father, a night porter, sleeps. When Mr. Wright tells Richard to kill a meowing kitten if that’s the only way he can keep it quiet, Richard has found a way to rebel without being punished. He takes his father literally and hangs the kitten. But Richard’s mother punishes him by making him bury the kitten and by filling him with guilt. Another theme is seen when his father deserts the family, and Richard faces severe hunger. For the first time, Richard sees himself as different from others, because he must assume some of the responsibilities of an adult. In contrast to his above characteristics, Richard soon shows his ability in learning, even before he starts school, which he begins at a later age than other boys because his mother couldn’t afford his school clothes. Rebellion, hunger (for knowledge and food), and the sense of being different will continue with Richard throughout this book.

In the following chapters the Wrights move to the home of Richard’s Aunt Maggie. But their pleasant life there ends when whites kill Maggie’s husband. Later the threat of violence by whites forces Maggie to flee again. Additional unfortunate events include Richard’s mother having a stroke. As a result, Richard is sent to his Uncle Clark’s, but he is unhappy there and insists on returning to his mother’s.

Later, Richard confronts his Aunt Addie, who teaches at the Seventh-Day Adventist church school. He also resists his grandmother’s attempts to convert him to religious faith. He writes his first story and blossoms in a literary sense. Richard then gets a job selling newspapers but quits when he finds that the newspapers hold racist views. Soon after this incident, his grandfather dies. Richard publishes his first story. The reaction from his family is overwhelmingly negative, though they can do nothing to stop his interest in literature.

When he graduates, Richard becomes class valedictorian. But he refuses to give the speech written for him by the principal. Upon entering the harsh world of actual adulthood, Richard has several terrifying confrontations with whites. In the most important of these confrontations, he is forced out of a job because he dares to ask to learn the skills of the trade. These same harsh realities of life also force Richard to learn to steal. By stealing he acquires enough money to leave the Deep South.

Richard finds a place to stay in Memphis. The owner of his rooming house encourages him to marry her daughter, Bess. As a result of his inborn fear of intimacy, he refuses. Richard then takes another job with an optical company. The foreman tries to provoke a fight between him and a black employee of another company. In the culmination of Richard’s interest in literature, he borrows a library card and discovers the hard-hitting style of columnist H. L. Mencken and begins to read voraciously.

Finally, in the last chapter, Richard leaves for Chicago. When Richard tells his boss that he is leaving, he says that his departure is at his family’s insistence. The white men at the factory are uneasy about a black man who wants to go north. They seem to consider that desire an implicit criticism of the South and thus of them. On the train north, Richard reflects on his life. He wonders why he believes that life could be lived more fully. His answer is that he acquired this belief from the books he read, which were critical of America and suggested that the country could be reshaped for the better. Wright seems to have wanted a different and better life long before he discovered Mencken and the other writers he read in Memphis. As Richard continues his reflections, he thinks the white South has allowed him only one honest path, that of rebellion. He argues to himself that the white South, and his own family, conforming to the dictates of whites, has not let him develop more than a portion of his personality. Yet he also thinks he is taking with him a part of the South. Here Wright focuses on the way his life in the South has been typical of other black lives, all stunted by racism.

Wright’s portrayal of himself growing up seems to be accurate; his personal feelings at the time of the book’s composition, and during his childhood adding to the reader’s understanding of the life and times of the author. Although an arguably confused and purposeless individual, Wright did achieve much in his strife against racism and its limits on his people. In becoming a community leader, he shared his perception about America, a perception of a part of America that was unknown territory. His admirable character allowed him to channel all the anger and ambiguities in his life and focus them to a good cause.