Female circumcision, better known as Female Genital Mutilation, is an ugly monster finally rearing its head from out of the depths of time. It can attack a girl at any age, with a little prompting from her society, and the aid of an unsuspecting human wielding the knife. Usually, it is performed from a few days after birth to puberty, but in some regions, the torture can be put off until just before marriage or the seventh month of pregnancy (Samad, 52).

Women that have gone beyond the primary level of education are much less likely to fall victim to the tradition (“Men’s…”, 34). The  average victim is illiterate and living in a poverty-stricken community where people face hunger, bad health, over-working, and unclean water (“Female…”, 1714). This, however, is not always the case. As one can see in the following story of Soraya Mire, social classes create no real barriers. Soraya Mire, a 13-year-old from Mogadishu, Somalia, never knew what would happen to her the day her mother called her out of her room to go buy her some gifts. When asked why, her mother replied, “I just want to show you how much I love you.” As Soraya got into the car, she wondered where the armed guards were. Being the daughter of a Somalian general, she was always escorted by guards. Despite her mother’s promise of gifts, they did not stop at a store, but at a doctor’s home. “This is your special day,” Soraya’s mother said. “Now you are to become a woman, an important woman.” She was ushered into the house and strapped down to an operating table. A local anesthetic was given but it barely blunted the pain as the doctor performed the circumcision.

average victim is illiterate and living in a poverty-stricken community where people face hunger, bad health, over-working, and unclean water (“Female…”, 1714). This, however, is not always the case. As one can see in the following story of Soraya Mire, social classes create no real barriers. Soraya Mire, a 13-year-old from Mogadishu, Somalia, never knew what would happen to her the day her mother called her out of her room to go buy her some gifts. When asked why, her mother replied, “I just want to show you how much I love you.” As Soraya got into the car, she wondered where the armed guards were. Being the daughter of a Somalian general, she was always escorted by guards. Despite her mother’s promise of gifts, they did not stop at a store, but at a doctor’s home. “This is your special day,” Soraya’s mother said. “Now you are to become a woman, an important woman.” She was ushered into the house and strapped down to an operating table. A local anesthetic was given but it barely blunted the pain as the doctor performed the circumcision.

Soraya was sent home an hour later. Soraya broke from her culture’s confining bonds at the age of 18 by running away from an abusive arranged marriage. In Switzerland, she was put in a hospital emergency room with severe menstrual cramps because of the operation. Seven months later, the doctor performed reconstructive surgery on her. Now in the U.S., Soraya is a leading spokeswoman against FGM (Bell, 58). In addition to being active in the fight against FGM, she is a American filmmaker. She has come a long way. Being well-educated about the facts of FGM also brings to light the ugly truth. “It is happening on American soil,” insists Soraya. Mutilations are occurring every day among innigrants and refugees in the U.S. (Brownlee, 57). Immigrants have also brought the horrifying practice to Europe, Australia, and Canada (McCarthy, 14). Normally, it is practiced in North and Central Africa (“Men’s…”, 34), the Middle East, and Muslim populations of Indonesia and Malaysia (“Female…”, 1714). Although it seems to have taken root in Muslim and African Christian religions, there is no Koranic or Biblical backing for FGM (“Men’s…”, 34). Many times female circumcision is treated as a religion in itself. It can be a sacred ritual meant to be kept secret forever. As a woman told poet Mariama Barrie, “You are about to enter Society {sic}, and you must never reveal the ritual that is about to take place.” (Barrie, 54). The ritualistic version of FGM is much more barbaric than the sterile doctor’s world which Soraya Mire passed through.

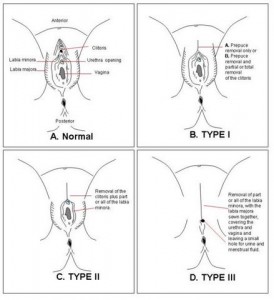

Mariama Barrie had to endure the most severe form of FGm at the tender age of ten. Mariama’s torture is known as infibulation. There  is also excision and sunna. Infibulation consists of the removal of the entire clitoris, the whole of the labia minora and up to 2/3 of the labia majora. The sides of the vulva are sewn or held together by long thorns. A small opening the size of the tip of a matchstick is left for the passage of menstrual blood and urine. Excision is a clitoridectomy and sometimes the removal of the labia minora; sunna is the only type that can truthfully be called circumcision. It is a subtotal clitoridectomy (“Female…”, 1714). To put this in perspective, infibulation would be like cutting off a man’s penis completely, cutting the testicles to the groin, and making a hole in them to have the semen siphoned out (McCarthy, 14). But still, it can get worse. The instruments that can be used to perform the operation are usually crude and dirty. they can include kitchen knives, razor blades, scissors, broken glass, and in some regions, the teeth of the midwife. Because of this, there are many dangers threatening the victim. The most immediate danger is exsanguination: there is no record of how many girls bleed to death because of this operation (“Female…”, 1715). Other physical consequences include infection, gangrene, abcesses, infertility, painful sex, difficulty in childbirth, and possibly death (“Men’s…”, 34). No matter how much we learn, the pain will still be the same as when the first female circumcision was performed in the fifth century, B.C. (McCarthy, 14). The number of women affected by this has risen steadily since then.

is also excision and sunna. Infibulation consists of the removal of the entire clitoris, the whole of the labia minora and up to 2/3 of the labia majora. The sides of the vulva are sewn or held together by long thorns. A small opening the size of the tip of a matchstick is left for the passage of menstrual blood and urine. Excision is a clitoridectomy and sometimes the removal of the labia minora; sunna is the only type that can truthfully be called circumcision. It is a subtotal clitoridectomy (“Female…”, 1714). To put this in perspective, infibulation would be like cutting off a man’s penis completely, cutting the testicles to the groin, and making a hole in them to have the semen siphoned out (McCarthy, 14). But still, it can get worse. The instruments that can be used to perform the operation are usually crude and dirty. they can include kitchen knives, razor blades, scissors, broken glass, and in some regions, the teeth of the midwife. Because of this, there are many dangers threatening the victim. The most immediate danger is exsanguination: there is no record of how many girls bleed to death because of this operation (“Female…”, 1715). Other physical consequences include infection, gangrene, abcesses, infertility, painful sex, difficulty in childbirth, and possibly death (“Men’s…”, 34). No matter how much we learn, the pain will still be the same as when the first female circumcision was performed in the fifth century, B.C. (McCarthy, 14). The number of women affected by this has risen steadily since then.

The average per year is now 2 million (McCarthy, 15), and it is their “female friends, mothers, and grandmothers who urge them to lie back and think of traditional culture” (“Men’s…”, 34). The reason women are promoting this practice is because “circumcisions are often carried out by select older women, whose profession provides them with a degree of public esteem rarely enjoyed by women in male-dominated societies” (Brownlee, 58). A better, but still not logical reason for women to promote FGM is life. Soraya Mire remarks, “[It] is proof of your virginity, and men only want to marry virgins. A Sudanese woman without a husband is not only an outcast, she is likely to die of starvation because she has no way to make a living on her own.” (Bell, 59) Many cultures support female circumcision because of ancient native beliefs. For example, some believe that bodies are androgynous at birth. To enter adulthood, girls “must be relieved of their male part, the clitoris” (Brownlee, 58). Others believe that the clitoris contains poison or will eventually grow to the size of a man’s penis (“Female…”, 1716).

WORKS CITED

Barrie, Mariama L. “Wounds that never heal.” Essence, (Mar. 1996), 54. Bell, Alison. “Worldwide women’s watch.” ‘TEEN, (June 1996), 58-59. Brownlee, Shannon and Jennifer Seter. “In the name of ritual.” U.S. News and World Report, (Feb. 7, 1994), 56-58. “Female genital mutilation.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, (Dec. 6, 1995), 1714-1716. “FGM: A universal issue.” Humanist, (Sep. 1996), 46. McCarthy, Sheryl. “Fleeing mutilation, fighting for asylum.” Ms., (July 1996), 12-16. “Men’s traditional culture.” Economist, (Aug. 10, 1996), 34. Samad, Asha. “Afterword.” Natural History, (Aug. 1996), 52-53.