Renaissance and its Implications

The Revival of Learning denotes, in its broadest sense, the gradual enlightenment of the human mind after the darkness of the Middle Ages. The names Renaissance and Humanism are often applied to the same movement. The term renaissance, which was first used in England, only as late as the nineteenth century, etymologically means “rebirth”.

Broadly speaking, the Renaissance implies the re-awakening of learning which came to Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Renaissance was not only English but a European phenomenon, and basically considered, it signaled a thorough substitution of the medieval habits of thought by new attitudes.

The dawn of Renaissance came first to Italy and a little later to France. To England it came much later, roughly about the beginning of the sixteenth century. In Italy, the impact of Greek learning was felt after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople the Greek scholars fled and took refuge in Italy carrying with them a vast treasure of ancient Greek literature in manuscript.

The study of this literature fired the soul and imagination of Italy at that time and created a new kind of intellectual and aesthetic culture quite different from the Middle Ages.

Firstly, the renaissance meant the death of medieval scholasticism which had for long been keeping human thoughts in bondage. The schoolmen got themselves entangled in useless controversies and tried to apply the principles of Aristotelian philosophy to the doctrines of Christianity, thus giving birth to a vast literature.

Secondly, it signaled a revolt against the spiritual authority-the authority of the Pope. The Reformation though not a part of the revival of learning, was yet a companion movement in England. This defiance, of spiritual authority, went hand and hand with that of intellectual authority, Renaissance intellectuals distinguished themselves by their flagrant anti-authoritarianism.

Thirdly, the Renaissance implied a greater perception of beauty and polish in the Greek and Latin scholars. This beauty and this polish were sought by Renaissance men of letters to be incorporated into their native literature. Further, it meant the birth of a kind of imitative tendency implied in the term “classicism”.

Lastly, the renaissance marked a change from the theocentric to the homocentric conception of the universe. Human values came to be recognized as permanent values, and they were sought to be enriched and illuminated by the heritage of antiquity. This brought a new kind of Paganism and marked the rise of humanism and also by implication, materialism.

The Impact of Renaissance on Prose, Poetry and Drama

Prose

The most important prose writers who exhibit well the influence of the Renaissance on English prose are Erasmus, Sir Thomas More, Lyly, Sydney. Erasmus was a Dutchman who, came to Oxford to learn Greek. His chief work was The Praise of Folly which is the English translation of his most important work written in England. Erasmus wrote this work in 1510.

Sir Thomas More’s Utopia was the “true prologue to the Renaissance”. It was the first book written by an Englishman which achieved European fame; but it was written in Latin (1516) and only later (1555) was translated into English. The word “utopia” is derived from the Greek word “ou topos” meaning no place. More’s utopia is an imaginary island which is the habitat of an ideal republic.

By the picture of the ideal state is implied a kind of social criticism of contemporary island. More’s indebtedness to Plato’s Republic is quite obvious. However, More seems also to be indebted to the then-recent discoveries of the explorers and navigators like Vasco da Gama-who were mostly of Spanish and Portuguese nationalities. In Utopia, More discredits medievalism in all its implications and exalts the ancient Greek culture.

Passing on to the prose writers of the Elizabethan age- the age of the flowering of the Renaissance- we find them markedly influenced both in their style and thought-content by the revival of antique classical learning. Sydney in Arcadia, Lyly in Euphues, and Hooker in The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity write the English which is away from the language of common speech; and is either too heavily laden- as in case of Lyly and Sydney- with bits of classical finery, or modeled on Latin syntax.

Further in his own career and his Essays, Bacon stands as a representative of the materialistic, Machiavellian facet of the Renaissance, particularly of Renaissance Italy. He combines in himself the dispassionate pursuit of truth and the keen desire for material advance.

Poetry:

Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-42) and the Earl of Surrey (1517-47) were pioneers of the new poetry in England. After Chaucer, the spirit of English poetry had slumbered for upward of a century. The change in pronunciation in the fifteenth century had created a lot of confusion in prosody which in the practice of such important poets as Lydgate and Skeleton had been reduced to a mockery. Wyatt had traveled extensively in Italy and France and had come under the spell of the Italian Renaissance.

It must be remembered that the work of Wyatt and Surrey does not reflect the impact of the Rome of antiquity alone, but also that of modern Italy. So far as the versification is concerned, Wyatt and Surrey imported into England various new Italian metrical patterns. Moreover, they gave poetry a new sense of grace, dignity, delicacy, and harmony, which was found by them lacking in the works of Chaucer and the Chaucerian’s alike.

Further, they were highly influenced by the love poetry of Petrarch and they did their best to imitate it. Petrarch’s love poetry is of the country kind, in which the pining lover is shown as a “servant” of his mistress with his heart tempest-tossed by her neglect and his mood varying according to her absence or presence.

It goes to the credit of Wyatt to have introduced the sonnet into the English literary, and of Surrey to have first written blank verse, both the sonnet and blank verse were later to be practiced by a vast number of the best English poets. Though in his sonnets, Wyatt did not employ regular iambic pentameters yet he created a sense of discipline among the poets of his times who had forgotten the lesson and example of Chaucer and, like Skelton, were writing “ragged” and “jagged” lines which jarred so unpleasantly upon the ear.

Wyatt wrote in all thirty-two sonnets, out of which seventeen are adaptations of Petrarch. Most of them (twenty-eight) have the rhyme scheme of Petrarch’s sonnets; that is, each has the octave a b b a a b b a, and twenty-six out of these twenty-eight have the c d d c e e sestet. Only in the last three, he comes near what is called the Shakespearean formula, that is, three quatrains and a couplet. In the thirteenth sonnet, he exactly produced it; this sonnet rhymes a b a b, a b a b, a b a b, c c. Surrey wrote about fifteen or sixteen sonnets out of which ten use the Shakespearean formula which was to enjoy the greatest popularity among the sonneteers of the sixteenth century.

Surrey’s work is characterized by exquisite grace and tenderness which we find missing from that of Wyatt. Moreover, he is a better craftsman and gives greater harmony to his poetry. Surrey employed blank verse in his translation of the fourth book of The Aeneid, the work which was first translated into English verse by Gavin Douglas a generation earlier, but in heroic couplets.

Drama:

The revival of ancient classical learning scored its first clear impact on England drama in the middle of the sixteenth century. Previous to this impact there had been a pretty vigorous native tradition of drama, particularly comedy.

This tradition had its origin in the liturgical drama and had progressed through the miracle and the mystery, and later the morality, to the interlude. John Heywood had written quite a few vigorous interludes, but they were altogether different in tone, spirit, and purpose from the Greek and Roman drama of antiquity.

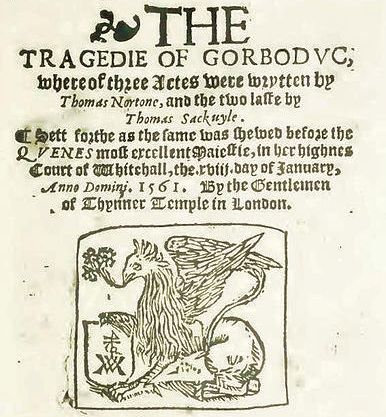

The first English regular tragedy Gorboduc and comedy Ralph Roister Doister were very much imitations of classical tragedy and comedy. Gorboduc is a slavish imitation of Senecan tragedy and has all its features without much of its life.

Like Senecan tragedy, it has revenge as the tragic motive, has most of its important incidents, narrated on the stage by messengers, has much of rhetoric and verbose declamation, has a ghost among its dramatis personae, and so forth. It is indeed a good instance of the “blood and thunder” kind of tragedy.

Later on, the “University Wits” struck a note of independence in their dramatic work. They refused to copy Roman drama as slavishly as the writers of Gorboduc and Roister Doister. Even so, their plays are not free from the impact of the Renaissance; rather they show it as amply, though not in the same way.

In their imagination, they were all fired by the new literature which showed them new dimensions of human capability. In this respect, Marlowe stands in the forefront of the University Wits. Rightly has he been called “the true child of the Renaissance”.