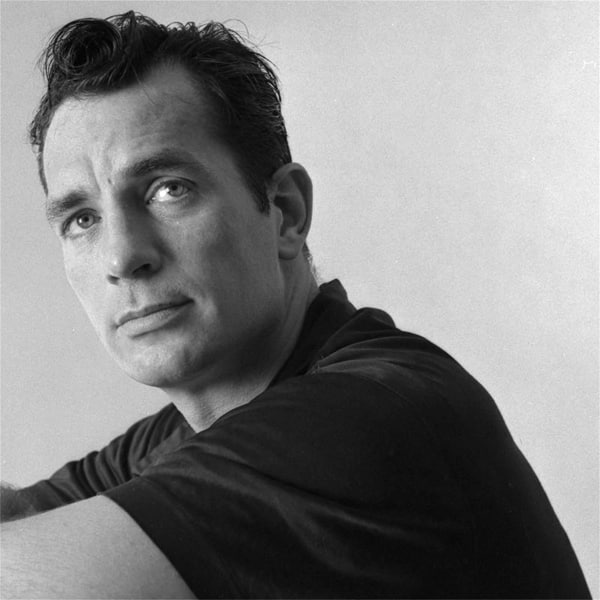

In the beginning Jack Kerouac lived a wild and exciting life outside the realm of everyday “normal” American life. Though On the Road and The Dharma Bums were Kerouac’s only commercial successes, he was a man who changed American literature and pop-culture. Kerouac virtually created a life-style devoted to life, art, literature, music, and poetry. When his movement grew out of his control, he came to despise it, and died lonely on the other side of what he once loved and cherished above all else.

But, on the way he created a style of writing which combined elements of all the great writers, with speed, common language, real people, and  the reality of his life. In a public junior high school he began to read feverishly. In English classes he flourished, but socially he did not. Impressed deeply by Mark Twain and Jack London, Kerouac created his own imaginary world, which he recorded in hand-written “newspapers.” These led to his first “novel” Jack Kerouac Explores the Merrimack, which he wrote in a notebook at the age of twelve (Clark, 22).

the reality of his life. In a public junior high school he began to read feverishly. In English classes he flourished, but socially he did not. Impressed deeply by Mark Twain and Jack London, Kerouac created his own imaginary world, which he recorded in hand-written “newspapers.” These led to his first “novel” Jack Kerouac Explores the Merrimack, which he wrote in a notebook at the age of twelve (Clark, 22).

Skipping classes at Lowell High School, in Lowell Massachusetts, Kerouac was exposed to the work of Thomas Wolfe by a fellow student Sammy Sampas. They encouraged writing in each other, and Kerouac began writing seriously. Since the Kerouacs could not afford college, a local priest suggested he try for a football scholarship (Clark, 32). He was offered two; one from Colombia University and the other from Boston College. Kerouac opted for Columbia and first spent one year, by the request of the university, at the Horace Mann School for Boys. Here he didn’t fit in with the rich prep- school crowd, but he was exposed to Hemmingway (Clark, 37). Here, also, in a school publication his work was first printed (Clark, 39). After two years of school at Columbia Kerouac made a decision that would change his life. He always believed he learned more outside of the classroom than in; and so after a series of arguments with his coach, he quit the team. Not long after he dropped out of school as well. He served briefly in the navy, and drinking heavily, was discharged on psychiatric grounds(Clark, 52). Upon his return home he got a job with as a Merchant Marine. When he wasn’t working he spent his time with Allen Ginsberg, Lucien Carr, William S. Burroughs, and Neal Cassady (Jack Kerouac, 1). His family’s disapproval of his friends led him to a life balancing his friends and family. This is recorded in The Town and the City, a novel which Ginsberg’s professors got published. Not long after Kerouac began making the now famous series of cross-country trips with Cassady immortalized in On the Road (On the Road). But it would be seven years before On the Road would be published (Jack Kerouac, 2). During these trips Kerouac made several literary discoveries that changed the American Novel. First and foremost he developed a “sketching” style of writing, inspired by an artist friend named Ed White and the speed of bop music. Here the main goal was to write on the spot.

This became what he called “the great moment of discovering my soul,” (Clark, 102). Later this “sketching” developed into a style of writing unlike any other. He would write either on the spot or from memory, but always on many levels; imagination and reality, psychic and social, poetry and narrative, but always complete honesty. To Kerouac this was “the only way to write.” This style is evident first in Visions of Cody, Kerouac’s tribute to Cassady (Clark, 110). In 1952 Kerouac lived briefly in Mexico City with Burroughs. Here he wrote Dr. Sax, which was considered shocking even by Ginsberg who told Kerouac it would never be published because it was “so personal, so full of sex language,” (Clark, 115). Later Kerouac said Ginsberg was mishandling his career and didn’t take advantage of the sex and drug revolution that was sweeping the country in paperbacks(Clark, 117). Ginsberg was wrong though. Dr. Sax was published, but not until 1959 (Clark, xvii). That fall he took a job with the Southern Pacific rail road. On the trains he developed another adaptation to his writing style. He called this “speed writing” which was supposed to “clack along all the way like a steam engine pulling a 100-car freight with a talky caboose at the end.” He also became well practiced in describing the American landscape, to the point where it almost becomes more of a character than a setting (Clark,118). The job on the rail road, and his writing led him to an isolation that brought a beauty to his writing similar to Dickinson. This is very evident when comparing On the Road with later works such as The Dharma Bums and Big Sur. But, Ginsberg believed the isolation was making him too focused on “self as subject matter” but, this is what had earlier drawn Ginsberg to Kerouac’s writing (Clark,119).

In 1953 Viking Press was still considering publishing Kerouac, Malcolm Cowley rejected three of his books, but still considered him “the most interesting writer who is not being published today.” Still On the Road remained unavailable to the American public (Clark, 123). Meanwhile, Kerouac was perfecting his “spontaneous writing” style by combining it with his new “spontaneous prose”. Falling deeper into the New York underground Kerouac began using heroin, dopophine, and barbiturates in addition to the marijuana and alcohol he had become accustomed to. This experience was recorded in The Subterraneans which Kerouac wrote in just one 72 hour sitting in which he lost 15 pounds. This was as Jack described “really a fantastic athletic feat as well as mental,” (Clark, 127). The manuscript thoroughly impressed Burroughs and Ginsberg who asked Kerouac to give them a detailed statement on his new style. Kerouac replied with a list titled The Essentials of Spontaneous Prose. This still remains the best explanation of Kerouac’s style; writing “without consciousness in semi-trance… excitedly, swiftly… from within, out -to be relaxed,” (Clark, 128). In 1954 Kerouac had possibly the most important interview of his life. John Holmes of The New York Times quoted Jack’s referral to his group of writer and artist friends as “the beat generation.” This became the title of the article in which Holmes stated “it was Jack Kerouac who invented the phrase, and his unpublished narrative On the Road is the best record of their lives,” (Clark, 133). A new chapter in Kerouac’s life began when he found religion in Buddhism. Kerouac moved again to Mexico City. Here he wrote some of his longest poems. These were combined into the 242 choruses of Mexico City Blues. This is described as “an extended sequence of free-association, spontaneous poems. He also began work on Tristessa which was not completed until the following year (Clark, 139). From Mexico City Kerouac moved to Berkley and became good friends with Gary Snyder, a Zen poet, (Jack Kerouac, 2).

Kerouac spent a great deal of time during this period on long hikes with Snyder, who was the complete opposite of Cassady. Snyder’s influence was good for Kerouac’s spirituality as well as his writing (Palmer). This time is recorded in the beautiful descriptions in The Dharma Bums (The Dharma Bums). 1955 was also the time of the now famous Six Gallery Poetry Reading. It is now considered the night of “the birth of the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance.” Here many of the “beat generation” writers and artists first gained fame. They were sad to see the man they regarded as the most talented of them so unhappy, carrying his life’s work around in a tattered rucksack (Jack Kerouac, 2). Finally, in 1957 On the Road was published and it became a best-seller. One Times critic referred to the publication as a “historic occasion in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment.” Kerouac was rapidly gaining fame, but after six years of literary rejection, he didn’t know how to handle it. He was older, sadder, and smarter than the public had expected. He tried to live up to his wild On the Road image, which only lead him down the dark spiral of alcoholism (Jack Kerouac, 2). The publication of On the Road coincided with Ginsberg’s  launch of the “united front,” a media campaign to join east and west coast artists. Ginsberg quietly slipped away to Europe and allowed Kerouac to bear the full force of the popular media. The media portrayed him as advocating illegal and immoral activities, but Kerouac was too drunk most of the time to intelligently deal with the criticisms and confrontations. He felt like “a kid dragged in by a cop,” (Clark, 164).

launch of the “united front,” a media campaign to join east and west coast artists. Ginsberg quietly slipped away to Europe and allowed Kerouac to bear the full force of the popular media. The media portrayed him as advocating illegal and immoral activities, but Kerouac was too drunk most of the time to intelligently deal with the criticisms and confrontations. He felt like “a kid dragged in by a cop,” (Clark, 164).

His fame was beginning to grow, but this hindered his writing. He became involved with the wife of respected literary critic Kenneth Rexroth. Initially Rexroth had regarded Kerouac as “the peer of Celine,” (Clark, 147). Needless to say, as Kerouac’s fame spread Rexroth’s opinion of him continued to decline until the point where Kerouac was regarded as “more pitiful than ridiculous.” Eventually, Kerouac fell into disregard with most critics (Jack Kerouac, 2). The critics, as well as Kerouac, believed the “beat generation” was simply a fad, but Kerouac believed his writing was above the fad (Jack Kerouac, 2). But by the time The Subterraneans was published critics were saying “The best way to read Kerouac is with an oxygen mask.” But, he Back in Lowell in 1961 Kerouac was hardly writing any more. The ladies of the town had organized a movement to get Kerouac’s books removed from the stores and libraries. Fed up, he moved with his mother to Florida. His last major writing effort began and in 10 days he finished Big Sur, the story of the alcohol delirium, paranoia, and madness he had suffered on a 1960 trip to California. It was written mainly as an apology and an explanation to everyone he had wronged during that time (Big Sur). By 1964 many of Cassady and Ginsberg were associating themselves more and more with the hippies of Ken Kesey, the Merry Pranksters, and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test fame (The Electric…). Kerouac, though, was a conservative at heart and avoided the psychedelic drug movement (Clark, 193). This eventually to Kerouac being despised by even those whose careers he began, and lives he had changed. In one meeting one of the Merry Pranksters had covered a couch with a flag. Ginsberg watched Kerouac slowly fold it up and “marveled sadly… history was… out of Jack’s hands now,” (Clark, 201). Neal Cassady died of a drug overdose in Mexico in 1968. Not long after, Jack Kerouac died of an abdominal hemorrhage and cirrhosis of the liver, he had literally drunk himself to death. He was only 47. He died a lonely death. A sad ending to the sad writer who gave so much of himself in his belief that “writing was his duty on earth.”

Works Cited

Clark, Tom. Jack Kerouac: A Biography. Paragon House. “Jack Kerouac.” 3 Oct.1998 <http://www.charm.net/~brooklyn/People/JackKerouac. html> Kerouac, Jack. Big Sur. New York: Viking Press, 1959. — The Dharma Bums. New York: Viking Press, 1958. — On the Road. New York: Viking Press, 1957. Wolfe, Tom. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. New York: Bantam Books, 1968.