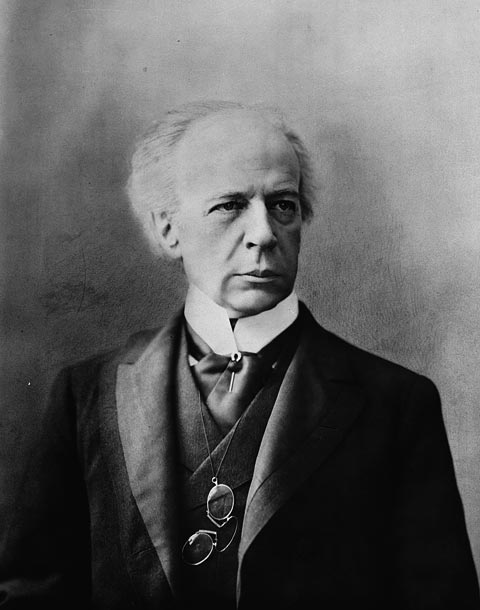

The first French Canadian to become prime minister of Canada was Wilfrid Laurier. Although French was his native tongue, he became a master of the English language. This and his picturesque personality made him popular throughout Canada, and he led the young country in a 15-year period of great development.

Wilfrid Laurier was born in St-Lin, Quebec, and studied law at McGill University. After three years in the Quebec legislature, he was elected to  the Canadian House of Commons in 1874. There he rose rapidly to leadership. Although he was a French Canadian and a Roman Catholic, he was chosen leader of the Liberal party in 1887. Nine years later he became prime minister. He was knighted in 1897.

the Canadian House of Commons in 1874. There he rose rapidly to leadership. Although he was a French Canadian and a Roman Catholic, he was chosen leader of the Liberal party in 1887. Nine years later he became prime minister. He was knighted in 1897.

“Build up Canada” were the watchwords of Laurier’s government. Laurier was loyal to Great Britain, sent Canadian volunteers to help in the Boer War, established a tariff favorable to British goods, and worked to strengthen the ties between the two countries. But he saw the British Empire as a worldwide alliance of free and equal nations, and he opposed every attempt to limit Canada’s freedom. Laurier’s liberal immigration policy brought hundreds of thousands of settlers to the western provinces. He reduced postal rates, promoted the building of railroads needed for national expansion, and appointed a commission to regulate railroad rates. After 15 years in office his government was defeated, presumably on the issue of reciprocal trade with the United States. Laurier believed, however, that his political defeat was caused primarily by opponents in Ontario who considered him too partial to Roman Catholic interests in Quebec. Prior to World War I, Laurier tried forcefully to support the formation of a Canadian navy. His own Liberal party defeated this measure, however, and Canada entered the war without a fleet of its own. During the early years of World War I, Laurier supported the war policy of Sir Robert Borden’s Conservative government. In 1917 he refused to join a coalition government that was formed to uphold conscription. Laurier felt that he could not back a measure so unpopular in the province of Quebec.

Wilfrid Laurier’s regime lasted 15 years. It was one of renewed growth and prosperity. The Manitoba School Question was promptly hushed up by new legislation enacted by the province in accordance with a compromise worked out with Ottawa. To his Cabinet Laurier drew some of the most capable leaders from every part of Canada. Business throughout the world was on an upswing, and the Laurier government was determined to get in on the action. The demand for Canadian wheat abroad encouraged immigration, and immigration in turn increased farm production and the value of national exports. “The 20th century belongs to Canada,” cried Laurier; and the whole nation took confidence from his assurance. Two new transcontinental railways were begun. By 1905 the west had expanded in both population and economic strength to such an extent that two new provinces, Alberta and Saskatchewan, were carved out of the Northwest Territories. These encouraging developments were inadvertently assisted by an occurrence in the far northwest. Since the Fraser River gold strike of 1858, prospectors had been consistently combing the mountainous areas of British Columbia and to the north. In 1896 their persistence paid off with the discovery of gold nuggets on the Klondike River in the far western Yukon Territory. When the news spread, the gold rush of 1897 began; it was to become the most publicized gold rush in history, eventually to be celebrated in the works of such writers as Jack London and Robert Service. The gold strike had some beneficial side effects. As miners poured into western Canada from the United States and other parts of the world, the extent of the unpopulated prairie lands became known. By this time, of course, the supply of free land in the United States had become exhausted, and the frontier was closed. Very soon after the gold rush, settlers began pouring into the western prairies of Canada by the thousands, from Europe as well as the United States. With much of Canada being unpopulated, this would help to create the massive population increase that Laurier was waiting for. More Canadian citizens would of course mean more taxes. More taxes would mean more money for the government. More money for the government would mean that Laurier could use the new financial wealth of the country to slingshot Canada’s status of being just a large cold country to the status of being a country where all were welcome and good land was available to people that were willing to put it to good use. They came from as far away as Russia to establish farms on the open wheatlands. It was not long before demands arose for the creation of at least one province between Manitoba and British Columbia. Thus, in 1905, the government in Ottawa formed two new provinces, Alberta and Saskatchewan. Another benefit resulting, at least in part, from the gold rush was the discovery of other minerals in the Canadian wilds. As early as 1883, nickel had been found at Sudbury, Ont. In the early 1890s large deposits of base-metal ores were found in southern British Columbia. After 1900 a rich deposit of silver was discovered north of Lake Nipissing in Ontario. Canada soon became perceived around the world as a mineral-rich nation with great untapped potential. The new prime minister thus basked in an environment of progress and prosperity after a depression that had lasted more than 20 years. Laurier’s only serious political difficulties stemmed from his inability to satisfy fully the imperialists among his followers. Great Britain received support in the Boer War of 1899-1902 from the other self-governing colonies, and Laurier reluctantly committed Canada as well (see Boer War). His decision, however, sharpened the controversy between the two nationality groups regarding Canada’s proper responsibilities to Britain in the future. On the other hand, he continued to resist pressures to tie the bonds of empire still more tightly during the years after the victory in South Africa. Seeds of distrust concerning his policies were thus sown on both sides of the wall that was rising between Canadians of French and of English descent. Another foreign policy issue arose as naval competition increased between Germany and Britain in the years before World War I. Great Britain naturally desired to receive military help from the colonies, and again Laurier found a compromise that satisfied neither the pro-British faction nor the French partisans. He founded the Canadian Navy in 1910 with the provision that in time of war it be placed under British command. This quickly led to accusations that Canadian soldiers would be drafted into the British Army if war came.

In 1911, when his opponents denounced his government’s decision to implement a limited reciprocity pact with the United States, Laurier felt he was on firmer ground and called a general election. His defeat, which occurred largely on this issue, showed that the prospering nation’s reservations regarding his policies were exceeded only by its lingering distrust of the United States. He believed that he was right, and that a lasting relationship with the United States would be beneficial and crucial to the development to both countries. People laughed at him and called him a fool for putting his trust in country such as the United States and Wilfrid Laurier died in Ottawa on Feb. 17, 1919 believing in his political ideas. He was right though; we need the United States to survive and they need us just as much as we need them. It was the people and politicians which followed in Laurier’s footsteps which has led us to our current relationship with the United States and the rest of the world. Sir Wilfrid Laurier was truly an incredible citizen, politician, strategist, and may have been the best prime minister this country will ever know.