There are different periods of the Assyrian empire. The first was called the Old Assyrian period which lasted from 2000-1550 BC. Then there was the Middle Assyrian period which lasted from 1550-1200 BC. The last was the Neo-Assyrian period which lasted from 1200-600 BC. The final phase of the Neo-Assyrian period is called the Assyrian Empire.

The Old and Middle Assyrian periods (2000 – 1200 BC)

The name Ashur was used by the Assyrians to designate not only their country but also their most ancient city and their national god. The cities of Ashur (near modern al-Sharqat), Nineveh, and Irbil formed a triangle that defined the original territory of Assyria. Assyria’s early history was marked by frequent episodes of foreign rule. Assyria finally gained its independence around 2000 BC.

About this time the Assyrians established a number of trading colonies in Cappadocia (central Anatolia), protected by treaties with local Hattic rulers. The most important of these was at Kultepe (Kanesh), north of present-day Kayseri, Turkey. Political developments Brought this enterprise to an end in 1750 BC. Assyria lost its independence to a dynasty of Amorite.

Then Hammurabi of Babylon took over and established himself ruler of Assyria. The collapse of Hammurabi’s Old Babylonian dynasty gave Assyria only temporary relief. It soon fell under the control of Mitanni, until that state was destroyed by the Hittites c.1350 BC.

The Early Neo-Assyrian Period (c.1200-600 BC)

After the collapse of Mitanni, Assyria regained its independence and was able to hold it thanks to the weakness of its neighbors. The most important event in Assyrian history during the 13 century BC, was the capture of Babylon by King Tukulti-Ninurta (r.1244-1208 BC). Although the conquest was short-lived the memory of it remained strong. In the following centuries, the chief adversaries of the Assyrians were the Aramaeans, who settled in Syria and along the upper Tigris and the Euphrates rivers, where they founded a number of states.

In the 9th century BC, under Ashurnasirpal II (r.883-859 BC) and Shalmaneser III (859-824 BC), the Assyrians finally managed to conquer Bit-Adini (Beth-Eden), the most powerful Aramaen state on the upper Euphrates. Shalmaneser then tried to invade the Syrian heartland, where he met with serious resistance from a coalition of kings that included Ahab of Israel. They successfully opposed him at the battle of Karkar in 853 BC. Internal disagreements marked the end of Shalmaneser’s reign, and many of his conquests were lost.

Assyrian power began with Tiglath-Peleser III (r. 745-727 BC) taking over the throne. He began administrative reforms aimed at strengthening royal authority over the provinces. Districts were reduced in size and placed under governors directly responsible to the king.

Outside Assyria, slave states were taken over and made into Assyrian provinces. In Syria, Tiglath-Pileser fought and defeated a number of anti-Assyrian alliances. In 732 BC he ruined Damascus, deporting its population and that of northern Israel to Assyria. In 729 he captured Babylon to guard against a Chaldean-led rebellion there and was proclaimed king of Babylon under the name Pulu (Biblical Pul).

His administrative reforms and military victories laid the foundation of the Assyrian Empire. Tiglath-Peleser’s son, Shalmaneser V, is remembered for his siege of Samaria, the capital of Israel (recorded in 2 Kings: 17-18). H died during the siege and was succeeded by Sargon II, who took credit for the destruction of Samaria and the exile of its people in 722 BC.

The end of the Assyrian Empire

The Assyrian Empire was faced with many challenges, Babylon successfully resisted Assyrian attempts to remove a Chaldean tribal chief who allied with Elam for over 10 years, a crusade against the northern state of Urartu, which resulted in their defeat and battling with rebellious coastal cities. The war against his Elamite ally continued for several years with indecisive results. Finally, after another revolt in Babylon, Sennacherib conquered the city and destroyed it in 689 BC. He was assassinated by members of his own family in 681 BC.

Esarhaddon (r.608-669 BC), son of Sennacherib, rebuilt Babylon and tried to appease the Babylonians. During his reign, incursions by the Cimmerians and Scythians posed serious threats to Assyrian possessions in Anatolia and Media (northwest Iran), the latter of which was a major source of horses for the Assyrian army. Esarhaddon’s principal accomplishment was the conquest of Egypt, begun by him in 675 BC, but completed by his son Ashurbanipal (r.668-627 BC). Ashurbanipal, was the last great king of Assyria and had to deal with many revolts. He led an expedition against Elam and captured Susa, it’s capital city.

After his death, however, the empire gradually disintegrated. In 626 BC, Nabopolassar, a Chaldean nobleman, proclaimed Babylonian independence and, allied with the Medes, set out to challenge Assyria. In the years 614-609, Ashur and Nineveh were captured by the Medes, and the Assyrian king fled to Harran on the northwest frontier. In 605 BC, Nabopolassar’s son, Nebuchadnezzar, defeated an Egyptian army that had come to the aid of the Assyrians, thus completing the destruction of the Assyrian state.

Assyrian Society and Culture

Before the development of modern archaeology, the Bible was the chief source of information about Assyria. The image of Assyria by the biblical accounts is one of irresistible military might. It was seen as an instrument of God’s wrath against sinful people.

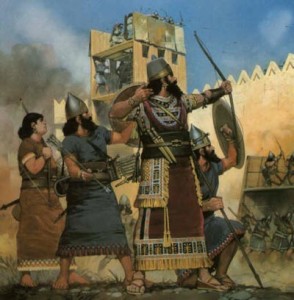

Archaeological excavations have unearthed the monuments and written records of the Assyrian kings, confirming this picture of military prowess and terrible brutality. They maimed, burned, speared, and denounced harshly their captives. They wanted to instill terror and discourage rebellion. They also deported to cities and farmlands the enemy populations.

Assyria dominated Babylonia politically, however, culturally was dependent on the south. The first major collection of cuneiform tablets discovered by 19th-century excavators–the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh–consists of myths, epics, rituals, lexical texts, wisdom literature, and prophetic and magical texts, providing a representative sample of Babylonian scholastic literature.

Assyrian art is usually associated with the colossal winged bulls and lions that guarded the entrances of their palaces, but even finer are the bas-reliefs on the palace walls and the carved ivories used to decorate their furniture. The bas-reliefs portray the Assyrian kings hunting, kneeling before their gods, or conquering foreign cities.