Food is a basic human need. It is far more important than almost any other industry. We can live without phones or cars, as they’re a luxury. But no one can live without food. Something has developed over the past twenty years; and the industrialization of food, at its worst. The global food chain is something that emerged after the second world war. It’s a web of trade, production, and corporations that control the flow of food for better or for worse. Much of this global food chain, however, is damaging to the world.

The main reasons are: the industrialization of food is putting a basic need in the hands of massive corporations, the environment is at a huge risk from the farm industry and related industries, and farmers in poorer countries are being abused by the global food chain

The industrialization of food is worldwide. But, given their economic power, America alone can show us a great deal of the corporate domination of food.

Small farms and the small shops that produced equipment for them or made things from their produce have all but died out in the face of corporate America. In the mid-1980s, following 235,000 failed farms, 60,000 small businesses also failed in rural communities (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 83). These failed farms would have their land purchased, and the corporate farms we know today began their expansion through them (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 4).

“Companies such as Tyson Foods work with thousands of individual ‘contract chicken growers’ who provide their own land and construct the sheds to raise the chickens, while the company owns the chickens and provides all the feed” (Paarlberg 131). This is the modern reality of farming in America.

As of 2019, Cargill is the biggest American agribusiness corporations. They produce nearly a quarter of meat and grain exports in America, and produce all kinds of farming equipment (Sekulich).

“Cargill is also directly involved in bringing local agricultural systems into the global/industrial orbit through its agricultural consulting work for multilateral development banks, aid agencies, and governments. Cargill’s agricultural consultants have so far worked in 116 countries” (Noreberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 91). They’re an example of how big many multinational agribusiness corporations are.

But with influence, comes control. Monsanto, another agribusiness giant, focuses a great deal of resources on patented GMO seeds.

The seeds are modified so only Monsanto brand herbicide will work on them. What’s more, is that unlike natural seeds, these seeds can only be used once. They even have a toll-free number to call if someone is found to be saving seeds (Noreberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 94-95).

Monsanto is ranked as the 6th largest agribusiness corporation in the world (Sekulich). As of 2010, 96% of genetically modified cotton in America was Monsanto brand (Paarlberg 130).

Farmaid is an organization dedicated to helping small farmers in various times of need. They claim a healthy market has 40% or less of the industry controlled by its top four firms.

But when they collected data in 2005, almost all agricultural goods had a higher percentage. At the highest, beef had 84%, corn had 80%, and soybeans had 70% (farmaid.org). There’s no question. A handful of companies have a monopoly on the global food chain.

In 2018, a senator in New Jersey even introduced a bill to temporarily stop agribusiness companies from merging, out of concern for the marketplace (Bloch). One of the mentioned concerns were as follows; “Four companies (Cargill, ADM, Louis Dreyfus, Bunge) now control 90% of the global grain trade” (Bloch).

“The prices that the farmer pays for the tractor and fertilizer, or gets for the crops and cattle, is determined in the boardroom, not even the dynamic marketplace” Said Fred Stokes, founder of Organization For Competitive Markets (Bloch).

Why is it such a problem? Because with a monopoly, comes control. And as it is, these companies can abuse any consumer or producer of food they have supplied, which is a large number.

The environment is one of the greatest victims of the global food chain. It can be understood best by starting with the poor farmer, who is most often in the developing world. “Farmers in poor countries lack political power, so they often find themselves trapped into practices that damage their own farm resource base and hence their own livelihood. Farmers in rich countries, because they have abundant political power, often use that power to push the environmental damage they do onto nonfarmers” (Paarlberg 110-111). We end up with two different issues from this.

Poor farmers will not have enough revenue to care for their land properly. Soil nutrients are exhausted due to not having enough fertilizer, land becomes waterlogged when irrigation is improperly maintained, and animals grazing eat at the remaining vegetation as they graze. All of these leave the land barren. Eventually, the land may be too barren to grow anything, forcing farmers to cut down nature to make room for more farmland” (Paarlberg 111-117).

“…According to the EPA[Environmental Protection Agency], in 2016 alone the amount of carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas that can increase in the atmosphere as a result of certain farming activities related to soil management — rose by 3.4 parts per million” (Netzley 58).

This number was the highest ever recorded (Netzley 58). “Soil contains carbon and other minerals as well as a variety of living things, such as microbes — tiny single-cell organisms that include bacteria and fungi. If the carbon disappears, the microbes cannot survive — and without microbes the soil becomes dirt, a sterile substrate in which many plants cannot thrive” (Netzley 62).

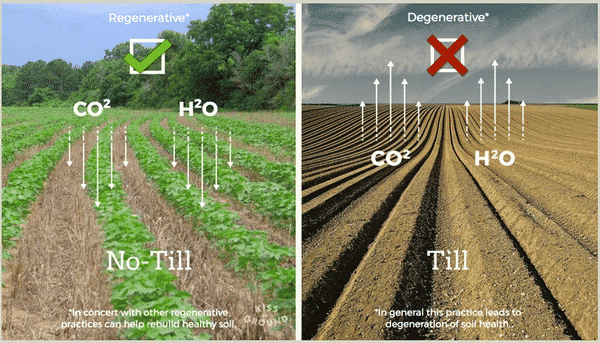

Tilling is one practice that releases the most carbon from the soil. Any practice that erodes the ground is a risk. The flooding of rice paddies is another large practice that encourages the release of methane from the soil, a substance thirty times more harmful than carbon dioxide (Netzley 64-66). In 2002, it was estimated that five pounds of topsoil were lost for every pound of grain harvested in Iowa (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 42).

Once the topsoil is gone, the deeper soil containing various greenhouse gases is reached over time by erosion. These greenhouse gases have and will contribute to global warming.

One tragic example of land being destroyed for farming purposes is the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil. People could be seeking land there for various reasons: perhaps their own land is lacking in fertility, or they can’t afford to legally purchase land, or they simply want to expand. When the trees from the rainforest are burnt, they leave behind fertile land from the ashes that is beneficial to farmers. This is the reason the Amazon was burning in 2019 (Lopes). “More than 30,000 fires burned in the rainforest in August alone, a nine-year high, according to the space research institute” (Lopes).

A lax in fines for deforestation helped cause this spike, but this tragedy still will have caused lasting damage, even if laws change. If there were no issues with land fertility, or affording land, then logically, there would be no need to clear more land. Food supply is not the issue, since the world produces 17% more food per person than it did 32 years ago (oxfam.ca).

Then what about the farmers who have enough resources? They, too, have many opportunities to damage the environment. German studies have shown industrial farming is the country’s leading cause for loss of biodiversity, causing over 500 plant species to go extinct or become endangered solely from agricultural practices (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 37).

The study was written in 1988, making it 31 years old. Data collected by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations found since 1900, about 75% of plant genetic diversity has been lost. They say it’s vital to the planet that farmers protect the remaining biodiversity (Netzley 31). Monocultures are large fields dedicated to single crops, such as mass cornfields in Kansas.

Farmers have to use specific seeds that will produce high yields and a crop able to withstand global transport if they want to stay on the global market. While this makes them short term money, their land is weakened by these practices. Biodiversity is lessened due to lack of diversity in crops planted, which is harmful to the land which farmers must continue to use (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 35-37).

Machinery had by wealthier farmers can put their land in equal danger. Small plants that help keep soil in place will be removed to make space for heavy machinery often compacts soil, and makes it hard for it to absorb water (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 42).

This can leave to the aforementioned erosion of topsoil, and release of soil carbon caused by different practices done by poor farmers. That isn’t the only thing done that hurts soil on massive farms.

“Those chemicals[chemical fertilizers, which are often used for large monoculture fields], as well as pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides, effectively end the symbiotic relationship between soil and plant by killing soil organisms, thus transforming the soil into a dead, toxic substance” (Norberg Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 42).

Factory farms are usually buildings which keep large quantities of livestock confined indoors, with very little space. They are given no opportunity to be healthy, in these poor conditions, and so disease spreads easily. This is usually solved with mass antibiotic application, but the overuse has rendered some bacterial strains incurable (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 59).

“Managing the animal waste produced by factory farms is an ongoing problem. Most operations store hog feces in unlined pits before pouring the waste into nearby fields known as lagoons. In North Carolina, flooding from Hurricane Matthew in 2016 inundated these lagoons, releasing untreated animal waste into waterways” (publicnewsservice.org).

Small farms immediately will use their manure, but factory farms cause terrible pollution from the excess fecal matter. Not only are streams, river, and groundwater often contaminated, but even air can be polluted. It was estimated in 1986 that 30% of acid rain in the Netherlands was due to industrial livestock operations (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 41).

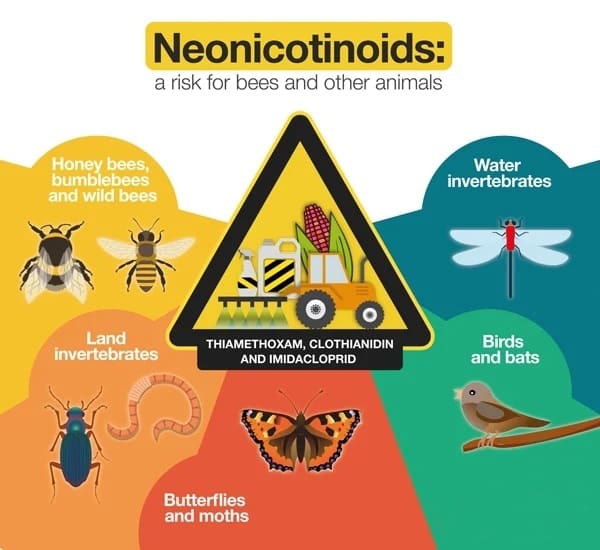

But it’s not just the land and livestock that are damaged, pesticides have also taken their toll. The risk factor is represented well in the example of neonicotinoids, and their damage to the bee population. A 2018 report by the EFSA(European Food Safety Authority), neonicotinoid insecticides are confirmed to harm bees. Europe passed it’s final ban on them that year (Stokstad).

“Neonicotinoids in farm soil can spread via water or wind-blown dust to nearby ground, where the pesticides are absorbed by weeds and wildflowers” (Stokstad). But in America, neonicotinoids are still used widely and have been since the early 2000s (Philpott). Why are bees so important? Because in 2010, bee pollination was estimated to contribute to $19 billion worth of agricultural production in America (Tucker). Bees are undoubtedly vital to the world’s ecosystems.

The issues caused by the global food chain, however, aren’t completely about growing food. There’s also the worldwide selling of it. Tons of food available in stores is foreign, and that which isn’t in stores can be ordered online. “It has been estimated that just one of these container ships, the length of around six football pitches, can produce the same amount of pollution as 50 million cars.

The emissions from 15 of these mega-ships match those from all the cars in the world. And if the shipping industry were a country, it would be ranked between Germany and Japan as the sixth-largest contributor to global CO2 emissions” (Piesing). This is just one example of the resources and pollution caused by transporting food across the world, rather than prioritizing local food. “Local foods have other environmental advantages over industrial foods.

Since local foods are more often consumed fresh, they usually require far less packaging, processing, and refrigeration: fresh peas, for example, require only 40 percent of the energy expended for a frozen carton of peas, and only 25 percent of an aluminum can of peas” (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 20). The data was collected by the London SAFE Alliance in 1996.

The excessive amount of packaging used to transport food worldwide is largely plastic and other non-biodegradable material. This non-biodegradable abundance of waste must be buried in landfills, as it takes so long to break down. To burn this trash would release so many toxins into the air, it’d be even more damaging (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 20).

While companies may be more incentivized to create minimalistic packaging in modern day by better technology and environmentalism, plastic padding and cardboard boxes are still widely used.

“According to CGIAR (formerly the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research) — a partnership of fifteen research centers around the world — the global food system is responsible for 33% of all greenhouse activity related to human activity.

The global food system includes everything related to growing crops, raising livestock, manufacturing products like fertilizers and pesticides, and storing, packaging, and transporting food” (Netzley 57).

Global warming itself, ironically, will be detrimental to agribusiness worldwide. Extreme weather is likely to cause flooding and drought, which will destroy farms all over, let alone various horrible effects (un.org).

Many would blame food shortage for the widespread chronic hunger in this world. However, in many countries, not being able to afford food is a bigger issue. What has long kept inequality is the global market. One key component unique to agribusiness is the huge farming subsidies provided by rich countries.

“Governments usually start subsidizing farmers during the initial industrial development. All economic sectors become wealthier in this industrialization process, including the farming sector, but the owners and operators of less competitive farms feel themselves losing from the process because more of their fellow citizens begin to earn even higher wages off the farm in the growing industrial sector” (Paarlberg 96).

Farming subsidies in America began in 1933 with the Agricultural Adjustment Act. At the time they were quite needed, as farmers made about half of what the average urban worker did, despite their roles being crucial. They used to come together to demand income support from government. But after the second world war, many went to get jobs in the city that offered higher pay. Remaining farmers became more stable with less competition and better technology.

As many began to buy more land and become richer farmers, they still receive subsidies based on land amount. In 2010 farmers made more than the average city worker if they owned enough property, a complete opposite of before. They still receive subsidies more than any other sector. Ironically, the largest 7% of farms got 45% of subsidies (Paarlberg 96-97).

If this is the case, then why do subsidies continue the way they are? Many would attribute it to the House and Senate Agriculture Committees, “…members from farm states and farm districts enjoy a dominant presence and are rewarded for their legislative efforts…” (Paarlberg 100). The reinstatement of the farm bill, which in 2008 would cost the American government $286 billion over five years, is supported by them.

They provide generous funding for food stamps, as well as the Conservation Reserve Program, as they pay farmers to leave their land temporarily idle, making sure to warrant support from all sides (Paarlberg 100-101). This shows the influence of agribusiness entities remains present in politics.

It isn’t only America that subsidizes their farmers. It’s a common practice amongst rich nations. In fact, the European Union’s subsidies contributed to 32% of all farmer’s earnings in 2010 (Paarlberg 95). What does this mean for the global market? It means it’s controlled.

The Brazilian government made a formal complaint against the United States in 2000 about cotton subsidies. They argued that without the United State’s subsidies, production in the country would’ve been 29% lower. American exports would’ve been 41% lower, and international cotton prices would be increased by 13% (Paarlberg 105).

With the market distorted, it becomes less surprising that farmers can’t afford to feed themselves. “Shockingly, about 70 percent of the billion hungry people in the world are farmers[as of 2011], herders and other food producers who could feed themselves if they had access to land, markets and a little bit of credit, said GRAIN’s Kuyek” (Leahy). The global market is a sensitive web of economics, and the weight of subsidies can’t be understood without elaborating on it.

The advancement of farming technology is described as pushing farmers on the global market along a treadmill; once one farm adopts the technology, all other farms must do so as well to match their yields and efficiency. The further their technology advances, the higher their yields become, whether because the pests couldn’t face their new pesticides, or an automatic watering system allowed them to expand their field. Either way, their field will have to expand eventually.

The higher the quantity of the produce produced worldwide, the less the produce is worth. Farmers may have to grow more food to make the same amount of profit. They may end up adopting even more technology to expand their fields, and the treadmill sends them onward. The treadmill is more than just a constant scramble; it causes debt. Farmers will take out bank loans to purchase the technology they require. They’ll accumulate debt, and have to pay it off over time, taking away from their profit.

The profit they gain on the global market, however, is already unstable. Farmers are at the mercy of all places selling their crop; a bountiful rice season in India may crush a farmer elsewhere by a price drop. All the while, they must deal with the aftermath of equipment that weakens their soil, and herbicides that lessen their biodiversity, both of which are bad for the crop. These are a few of the many reasons small farmers have such a hard time surviving on the global market (Norberg-Hodge, Merrifield, Gorelick 4-8).

As was aforementioned, many of the biggest farm corporations produce farming technology, from machinery, to pesticides, to seeds. Because they have such a monopoly with such technology, in a way, they control the price of food. As aforementioned, America heavily subsidizes their farming sector, which ends up mostly feeding large agribusiness farms owned by corporations. Because the corporations are rich, and heavily subsidized, they can afford to sell produce at prices below the cost of production.

“In reality, farm subsidies allow food to be sold on supermarket shelves at prices below the commercial cost of producing it” (Wright). This is stated by The Scottish Farmer in 2019, just as it has been a fact for decades, in many countries, whether because of high subsidies from the government or the company they work for. It becomes inevitable that poor, unsubsidized farmers will make little profit due to this system.

Most of these sorts of farmers will be found in developing countries, or poorer countries. This ties into chronic hunger in the world, but another phenomenon contributes a great deal to farmers having no food for themselves. “For example, in Guatemala, much of the land is devoted to the production of bananas and citrus fruits (97% of the citrus crop is exported), which means that majority of the basic food products needed by the native people are imported from other countries” (encyclopedia.com).

Cash crops. Rich countries will import plenty of exotic foods, or even things they can grow in that country to feed their people daily. Many farmers in developing countries grow crops solely intended to be exported, which, in some places, contributes to chronic hunger.

“Famine-hollowed farmers watch trucks loaded with grain grown on their ancestral lands heading for the nearest port, destined to fill richer bellies in foreign lands. This scene has become all too common since the 2008 food crisis” (Leahy).

For the farmer living in a poor community, where people may not be able to pay much for food, selling to the global market may end up being ideal.

“More than 100 billion dollars has been invested in buying farmland since 2008[as of 2011], mainly in Africa by foreign companies and foreign-state owned industries, according to GRAIN, a small international non-profit organisation that works to support small farmers” (Leahy). This meant employing African farmers to grow crops for rich countries.

Agribusiness corporations can gain a great deal from setting up in developing countries. Poor countries generally won’t have the funds or resources to enforce environmental laws. Moussa, a Malian cotton farmer, tells the following to a journalist: “I have a headache all the time,” he explains. “Working with the pesticides makes you sick; it makes your head sore, your stomach ache” (Day).

He lives a hard life. “Moussa, who started growing cotton 17 years ago [as of 2010] farms two hectares of land, which yield 500-800 kilos a year. Yet despite the quantity and quality of cotton he produces, he is barely able to feed his children” (Day).

“According to calculations done by Oxfam America [in 2010], if U.S. cotton programs were eliminated and if the international price of cotton consequently increased by 6 to 14 percent, eight very poor countries in West Africa could be able to earn an additional $191 million each year in foreign exchange from the cotton exports…” (Paarlberg 105).

It’s the global food chain that is a big reason farmers in the developing world live in such harsh poverty.

Have the amount of hungry farmers decreased in Africa since then? Not exactly. “There has been the least progress in the sub-Saharan region, where about 23 percent of people remain undernourished – the highest prevalence of any region in the world.

Nevertheless, the prevalence of undernourishment in sub-Saharan Africa has declined from 33.2 percent in 1990– 92 to 23.2 percent in 2014–16, although the number of undernourished people has actually increased (FAO et al., 2017)” (worldhunger.org).

In the current global food chain, it is often made impossible for the farmer in the developing world to get away from hunger and climb out of poverty.

The modern global food chain is a practice that is bad for this world. It puts a monopoly over food in the hands of profit-oriented corporations, accounts for a great deal of environmental destruction, and abuses farmers in developing countries.

Only if the system changes can things improve. In a world where poor farmers in developing countries can’t afford to farm sustainably, we certainly can’t save the planet. In a world where the environment is damaged so heavily by farming practices, and these practices are furthered by both massive corporations and a large number of impoverished farmers, we cannot save the planet.

And if there is no planet, there will be no agriculture left for agribusiness.

Works Cited

“2018 World Hunger And Poverty Facts And Statistics.” Hunger Notes, https://www.worldhunger.org/world-hunger-and-poverty-facts-and-statistics/. Accessed 11 Dec 2019

Bloch, Sam “The New Jersey Senator Has Introduced A Bill To Halt The Mergers And Acquisitions That Have Hamstrung Small-Scale Producers For Decades.” The New Food Economy, 30 Aug 2018, https://newfoodeconomy.org/cory-booker-agribusiness-merger-moratorium-antitrust-bill/. Accessed 7 Dec 2019

“Cash Crops.” Encyclopedia.com, 4 Dec 2019, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/sociology-and-social-reform/sociology-general-terms-and-concepts/cash-crop. Accessed 11 Dec 2019

“Climate Change.” United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/climate-change/. Accessed 7 Dec 2019

“Corporate Control In Agriculture.” Farm Aid, https://www.farmaid.org/issues/corporate-power/corporate-power-in-ag/. Accessed 7 Dec 2019

Day, Elizabeth “The Desperate Plight Of Africa’s Cotton Farmers.” The Guardian, 14 Nov 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/nov/14/mali-cotton-farmer-fair-trade. Accessed 8 Dec 2019

Leahy, Stephen “In Corrupt Global Food System, Farmland Is The New Gold.” 13 Jan 2011, http://www.ipsnews.net/2011/01/in-corrupt-global-food-system-farmland-is-the-new-gold/. Accessed 8 Dec 2019

Netzley, Patricia D. Science and Sustainable Agriculture. ReferencePoint Press, Inc. 2018. Print.

Norberg-Hodge, Helen, Merrifield, Todd, and Gorelick Steven. Bringing The Food Economy Home. ISEC, 2002. Print.

Paarlberg, Robert. Food Politics What Everyone Needs To Know. Oxford University Press, Inc. 2010. Print

Philpott, Tom “Europe Just Banned the Chemicals That Lay Waste to Honeybees. But They’re Still Everywhere in the US.” Mother Jones, 3 May 2018, https://www.motherjones.com/food/2018/05/europe-neonicotinoid-bees-chemical-syngenta-dow/. Accessed 9 Dec 2019

Piesing, Mark “Cargo Ships Are The World’s Worst Polluters, So How Can They Be Made To Go Green?” iNews, 4 Jan 2018, https://inews.co.uk/news/long-reads/cargo-container-shipping-carbon-pollution-515489. Accessed 10 Dec 2019

“Report: Factory Farming Driving Global Environmental Crisis.” Public News Service, 14 May 2019, https://www.publicnewsservice.org/2019-05-14/environment/report-factory-farming-driving-global-environmental-crisis/a66445-1?fbclid=IwAR0zey6WlTzrO61CgV7iyDlv9An1hPZisGTNmuRgSrjbOwNkCSinJR5EArs. Accessed 9 Dec 2019

Stokstad, Erik “European Agency Concludes ‘Neonic’ Pesticides Threaten Bees.” Science, 28 Feb 2018, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/02/european-agency-concludes-controversial-neonic-pesticides-threaten-bees. Accessed 9 Dec 2019

Sekulich, Tony “Top Ten Agribusiness Companies In The World.” Tharawat Magazine, 7 Feb 2019, https://www.tharawat-magazine.com/facts/top-ten-agribusiness-companies/#gs.m1p1do. Accessed 8 Dec 2019

“There Is Enough Food To Feed The World.” Oxfam, 5 Sep 2019, https://www.oxfam.ca/publication/there-is-enough-food-to-feed-the-world/. Accessed 10 Dec 2019

Tucker, Jessica “Why Bees Are Important To Our Planet.” One Green Planet, Jan 2019, https://www.onegreenplanet.org/animalsandnature/why-bees-are-important-to-our-planet/. Accessed 9 Dec 2019

Wright, Richard “Farm Subsidies Allow Food To Be Sold Below The Cost Of Production.” The Scottish Farmer, 8 Jan 2019, https://www.thescottishfarmer.co.uk/opinion/17343449.farm-subsidies-allow-food-to-be-sold-below-the-cost-of-production/. Accessed 10 Dec 2019