Drama and the Folk Ritual

Drama had its earliest beginnings in the corporate life of the village, the predominant form of settlement that took place in England in c.450, with the coming of the Anglo-Saxons. The villagers had to undertake the communal task of plowing, reaping and harvesting, and clearing the wasteland. This pattern of work and the survival of the community were determined by cycles of cultivation and change in seasons.

And this in turn expressed itself in rituals that fed into mythologies. The rituals were performed as types of worship that both ensured the continuity of the cycles and acknowledged their significance. With the coming of Christianity in 597, these rituals were demythologized in accordance with Christian beliefs and at the same time, their communal functions acquired new forms. The rituals retained a lot of their vigor through the Middle Ages developing themselves into the folk play.

What is interesting is that the Church always disapproved and was of the element of ‘playing’ in these folk customs. This kind of censorship continued well into the Elizabethan period, with theatre being associated with the hellish art of feigning, license and misrule. The fact that it survived despite the continuous suppression speaks immensely for its vitality.

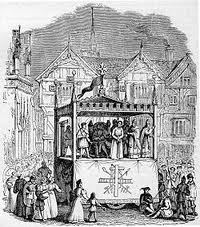

The native drama grew out of the activities of minstrels, strolling players, storytellers, and entertainers who worked outside any formal tradition of theater. They were part of processions, pageants, and tournaments, using the village green and town square as the playing area or platea (Latin for open acting space).

Most of their performances were ritualistic in nature, using, for instance, the fertility myths to celebrate the spirit of fecundity and regeneration. Later, with the domination of the Christian myth, the pagan ritual lost its primary function. As community activities, these rituals did not require texts, so that many folk plays survived as mimetic actions alone. It was only much later that they were re-inscribed into texts as a rationalization for performances that may have taken place.

Recently, critics have challenged the theory that the history of drama marks an evolution from a primitive human activity that led to being polished and refined into the unique dramatic achievement of the Renaissance. Nothing could be further from the truth, they insist. The religious drama of the medieval period had a distinct shape and content; it was also flourishing when the church and the authorities stopped it.

Drama Within the Church

There is little doubt that the church was at the center of medieval life. It catered to both the social and spiritual needs of people. But what is truly fascinating is the way that it harnessed drama for its own purpose. It found in the dramatic form, an ideal vehicle for conveying its sermons. In fact, the rituals observed in the church had all the ingredients of drama.

Notable amongst them was the mass. It had colorful robes and vestments; a procession from the churchyard to the inner sanctuary led by the bishop and his attendants and often accompanied by the comic figure of the boy bishop. It had choral singing and on special occasions as Christmas and Easter, the atmosphere was heightened by the use of candlelight incense and music.

The central nave of the church had the pulpit and space for the choir, while the church could hold a compact congregation. In many ways, the architecture of the building was like a natural theatre. The pulpit was used as a natural stage to preach sermons. Folk rituals were mediated by Christian myths and sometimes the church actively participated in supervising such ceremonies.

Miracle Plays

Once outside the church, the drama flourished and soon became independent, although its themes continued to be religious and its services connected with religious festivals. In 1264, Pope Urban added to the religious calendar a new, important feast: Corpus Christi, celebrated beginning on the first Thursday after Trinity Sunday, about two months after Easter, as a part of thanksgiving to Jesus Christ, for His sacrifice on the cross.

Miracle plays, on the subject of miracles performed by saints, developed in the twelfth century in both England and on the continent. Typically, these plays focused on the Virgin Mary and Saint Nicholas, both of whom had strong followings during the medieval period. Mary is often portrayed as helping those in need and danger- often at the last minute. Some of those she saved may have seemed unsavory sinners to a pious audience, both the point was that the saint saved all who truly wished to be saved.

Although they quickly became public entertainers removed from the church building and were popular as Corpus Christi entertainers throughout the fifteenth century, few miracles plays survive in English because King Henry VIII banned them in the middle of the sixteenth century, during his reformation of the church. the craft guilds, professional organizations of the workers involved in the same trade- carpenters, wool merchants, and so on-soon began competing with each other in producing plays that could be performed during the feast of Corpus Christi.

Most of their plays derived from the biblical stories and the life of Christ. Because the bible is silent on many details of the life of Christ, some plays invented a new material and illuminated dark areas, thereby satisfying the intense curiosity medieval Christians had about events the bible omitted.

Mystery Plays or The Mystery Cycles

Once outside the church, the drama flourished and soon became independent, although its themes continued to be religious and its services connected with religious festivals. In 1264, Pope Urban added to the religious calendar a new, important feast: Corpus Christi, celebrated beginning on the first Thursday after Trinity Sunday, about two months after Easter, as a part of thanksgiving to Jesus Christ, for His sacrifice on the cross.

Miracle plays, on the subject of miracles performed by saints, developed in the twelfth century in both England and on the continent. Typically, these plays focused on the Virgin Mary and Saint Nicholas, both of whom had strong followings during the medieval period. Mary is often portrayed as helping those in need and danger- often at the last minute. Some of those she saved may have seemed unsavory sinners to a pious audience, both the point was that the saint saved all who truly wished to be saved.

Once outside the church, the drama flourished and soon became independent, although its themes continued to be religious and its services connected with religious festivals. In 1264, Pope Urban added to the religious calendar a new, important feast: Corpus Christi, celebrated beginning on the first Thursday after Trinity Sunday, about two months after Easter, as a part of thanksgiving to Jesus Christ, for his sacrifice on the cross.

Miracle plays, on the subject of miracles performed by saints, developed in the twelfth century in both England and on the continent. Typically, these plays focused on the Virgin Mary and Saint Nicholas, both of whom had strong followings during the medieval period. Mary is often portrayed as helping those in need and danger- often at the last minute. Some of those she saved may have seemed unsavory sinners to a pious audience, both the point was that the saint saved all who truly wished to be saved.

Morality Plays

MORALITY PLAYS were never a part of any cycle but developed independently as moral tales in the fourteenth or early fifteenth century on the Continent and in England. They do not illustrate moments in the Bible, nor do they describe the life of Christ or the saints.

Instead, they describe the lives of people facing the temptations of the world. The plays are careful to present a warning to the unwary that their souls are always in peril, that the devil is on constant watch, and that people must behave properly if they are to be saved.

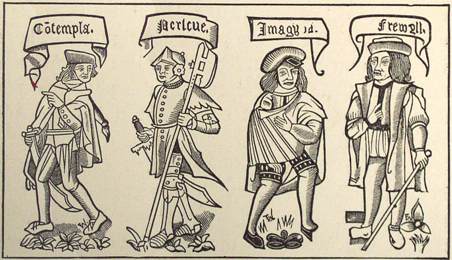

One feature of the morality plays is their reliance on the technique of ALLEGORY, a favorite medieval device. Allegory is the technique of giving abstract ideas or values a physical representation. In morality plays, abstractions such as goodness became characters in the drama. The use of allegory permitted the medieval dramatists to personify abstract values such as sloth, greed, daintiness, vanity, strength, and hope by making the characters and putting them on stage in action.

The dramatists specified symbols, clothing, and gestures appropriate to these abstract figures, thus helping the audience recognize the ideas, the characters represented. The use of allegory was an extremely durable technique that was already established in medieval paintings, printed books, and books of the emblem, in which, for example, sloth would be shown as a man reclining lazily on a bed or greed would be represented as overwhelmingly fat and vanity as a figure completely absorbed in a mirror.

The central problem in the morality play was the salvation of human beings, represented by an individual’s struggle to avoid sin and damnation and achieve salvation in the other world. As in Everyman, (c. 1495), a late medieval play that is best known as the morality plays, the subjects were usually abstract battles between specific vices and certain virtues for the possession of the human soul.

In many ways, the morality play was a dramatized sermon designed to teach a moral lesson. Marked by high seriousness, it was nevertheless entertaining. Using allegory to represent abstract qualities allowed the didactic playwrights to draw clear-cut lines of moral force: Satan was always bad; angels were always good. The allegories were clear, direct, and apparent to all who witnessed the plays.

Interludes

The interludes signify the important transition from symbolism to realism. It appeared towards the end of the fifteenth century but it could not displace the morality which continued enjoying popularity, as we have pointed out above, till the end of the sixteenth century. It dispensed with the allegorical figures of the morality play almost completely and affected a complete break with the religious type of drama, even though retaining some of its didactic characters. It was purely secular and fairly realistic, though quite crude and somewhat grotesque.

Nice, thanks