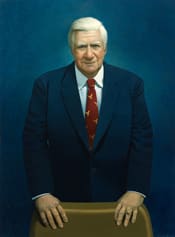

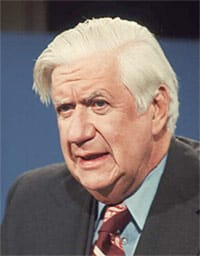

Tip was a man who was not bashful to call himself “a man of the house.” Thomas P. O’Neill was a person whose greatest charm was that he seemed “completely out-of-date as a politician.” (Clift) He was a gruff, drinking, card playing, backroom kind of guy. He had an image that political candidates pay consultants to make over. He knew these qualities gave him his power because they “made him real.” (Sennot 17) His gigantic figure and weather beaten face symbolizes a political force of five decades, from Roosevelt’s new deal to the Reagan retrenchment. He was the last democratic leader of the old school and “the longest-serving speaker of the house (1977-1986) and easily the most loved.” (Clift)

Thomas P. O’Neill (1912-1994) always knew why he was in Washington, and what he stood for. He was a native of Boston and always prided  himself on his theory that “all politics is local.” (O’Neill 1) Tip was a friend of everyone. When ordinary people wanted something of O’Neill he gave it to them. When anyone asked him a favor, he would do it. O’Neill served fifty years in public life and retired with only fifteen thousand dollars to his name. He devoted his life and his money to the people of Boston.

himself on his theory that “all politics is local.” (O’Neill 1) Tip was a friend of everyone. When ordinary people wanted something of O’Neill he gave it to them. When anyone asked him a favor, he would do it. O’Neill served fifty years in public life and retired with only fifteen thousand dollars to his name. He devoted his life and his money to the people of Boston.

Tip came of age in the Great Depression, arrived in congress from Massachusetts in 1952 and “came to power amid the plenty of the ’60s and ’70s.” (Woodlief 4) He was a rampant liberal who “would usually vote yes on any bill that helped people (he once voted to put money into an appropriations bill to study knock knees).” (Gelzinas 6) When Reagan came into office in 1980 big government began to feel the pinch and O’Neill’s big hearted liberalism was on the way out. In 1980, O’Neill was a target of a clever Republican ad campaign that pictured him in a limo as a symbol of a bloated out of control congress. The advertisement backfired and it sent O’Neill into folk hero status. Tip even “made an appearance on “Cheers” as an effect of the advertisement.” (Time 18)

Tip said that he “only made one vote that he regretted.” (O’Neill 218) It was a yes vote on the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that gave Lyndon Johnson full control over all military intervention in Vietnam. He did this because it was a time when Congress did what leadership asked, in fact there was not one descending vote in the house on this issue (414-0). Right away he had speculation that the White House might use this as a device to open up full scale war in Vietnam. Tip had many questions about the war in Vietnam, but at first stuck with the saying by Samuel Rayburn, “When it comes to foreign policy- support the Pres.”

His attitude changed. He felt if the U.S. was to fight they should fight to win, and he did not think this was the case. Student kept badgering him with questions of his support of the foreign policy of Dean Rusk, the secretary of state. Finally a student got him with a question. A student at Boston College, Tip’s alma matter, said, “Sen. O’Neill you have told the public about your many briefings of the war by General Westmoreland, Robert McNamara, the CIA, and even President Johnson but have you ever considered hearing the briefings of the other side?” This hit Tip head on. He decided to get a good look on the other side of the issue.

He began his investigation at his best negotiating table, the poker table. At the Army and Navy Club in Washington. At the table were Generals and other high ranking military officials. Three losing games and a couple dozen drinks later Tip started to ask questions. He found that all these pentagon officials felt that we should not send troops to Vietnam unless we plan to win. Johnson didn’t want the soldiers to take the  offensive.

offensive.

They were not the only ones. Most CIA officials and members of the defense department who openly supported Johnson’s stance were “saying the opposite after a few beers.” (O’Neill 233) Tip was invited to a private dinner of CIA officials and there everyone he met was openly against the war because they felt it was unwinnable, but the all pledged publicly with Johnson. These CIA officers said all foreign officials were against the war as well as the American public. They pleaded for Tip to come out into the open to oppose the war. They told him to tell Speaker McCormack that the entire Central Intelligence Committee is opposed to the war. Tip could not because McCormack was a war hawk that would not oppose the president.

In June of 1967, Tip went to Malta for vacation. By coincidence Malta was the place where American soldiers were brought from Vietnam for rest and relaxation between tours of duty. Tip was smoking a patented cigar in a bar when group of U.S. soldiers entered. Tip introduced himself to one of the soldiers who was ironically from Buzzards Bay. He recognized Tip and introduced him to his fellow marines. Tip being himself opened up the bar. He found from the guys that they did not object to being in Vietnam. They did object to the U.S. stategy of the war. The soldiers could not fire unless being fired apron, the could use no land or sea mines and did not select any targets. The troops did not understand why they were in Vietnam because they said it was simply a Civil War the U.S. should have no interest in. Tip came to the conclusion that we were in a conflict “that we could not win- that we were not even trying to win- and could be stuck in for years taking huge U.S. casualties.” (O’Neill 232)

In September 1967, Tip made up his mind. He was not going to publicly support the war any longer. The Vietnam conflict was a civil war and U.S. involvement was wrong. He decided not to go to the press (because he never did before), but to write a newsletter to his constituents. In the letter he “took the stand as a citizen, a congressman, and a father that by remaining in the Vietnam we were paying too high of a price in both innocent human lives and money.” (O’Neill 233) He outlined instructions for Johnson in the letter. They are as follows:

1) Stop further escalation and attempt to bring the conflict before the UN.

2) Stop bombing of the North.

3) Promote an Asian solution to an Asian problem.”

He sent the letter and told his sun Tommy that he had signed “his political death warrant.” (Edwards 25)

People in Boston wanted to kill Tip but he knew it was the right thing to do. All his political colleagues and constituents were lost. Every one. Tip was getting the squeeze from his voters and the Democratic Party. His approval rate went from around eighty percent to about fifteen.  Rioting college students were referred to Tip’s kids. Tip was infuriated at being blamed for their actions. The Boston Globe printed a headline in response to riots that said,” O’Neill is Dove, academic community influence.” Tip regarded this is “Bullshit!” and said recently in response,”[He] opposed the war not because of the students but in spite of them.” (Rosen)

Rioting college students were referred to Tip’s kids. Tip was infuriated at being blamed for their actions. The Boston Globe printed a headline in response to riots that said,” O’Neill is Dove, academic community influence.” Tip regarded this is “Bullshit!” and said recently in response,”[He] opposed the war not because of the students but in spite of them.” (Rosen)

When the letter was first sent out no one knew of it actual contents. The Washington Post received a copy of the letter and ran it on September 14, 1967. The Secret Service was out to find Tip. They searched for ten hours. No one could find him. He showed up at his home three hours after the Secret Service gave up. He explained he had hot hand at the card table in a backroom of a local bar. The President ordered to see Tip the next day.

President Lyndon Johnson had a private meeting with Tip in the Oval Office, his first time alone with the president. The President said,” Tip, what kind of son of a bitch are you? I expect shit like this from those assholes like Bill Ryan (an ultra-liberal from New York). Tip, I’ve been friendly to you since you came to Washington, What do you think you know more about this fucking war than I do?”

Tip replied, “Mr. President, no. But in my heart and in my conscience I believe you are wrong. You can’t fight your damn war when everyone else knows it is wrong! You can’t expect America to stand behind you when you’re fighting your war that can’t be won.”

After the President brief Tip on the situations of the war he hugged Tip and told him, “I am glad you had the balls to tell me, I very glad you came in to explain yourself… I now understand you are doing this because you really care.”

The President saw something that is rare in politics. Tip was not the best speaker but everybody knew he didn’t care what others thought of him. He voted because he “really cared.” (Edwards 25) We must thank God for men like Thomas P. O’Neill. Thomas P. O’Neill did not vote to stay on the public payroll. Tip was a man who is a better example of how our political system can work. President Johnson decided not to be re-elected as President because he realized he caused a terrible war and for that he should never be forgiven. Tip took a possible chance of vanishing into obscurity. Congress eventually swayed on Tip’s side and the incident was forgotten in the minds of the public.

Thomas P. O’Neill was Mr. Speaker. He was a man who took all comers and played hardball in Politics, and was their instant friend as soon as they left the senate chambers. Thomas P. O’Neill will always be close to home no matter where he has gone. “Rest well, and thank you Mr. Speaker.” (Gerald Ford)

Works Cited

Clift, Elanor. “Last Hurrah for Tip.” Newsweek 17 January 1994: 22

Edwards, Mickey. “Let’s hope Tip wasn’t the Last of his kind.” Boston Herald 11 January 1994: 25.

Gelzinas, Peter. “Despite the pomp, he was a family man.” Boston Herald 11 January 1994, morning edition: 6.

Holmes, Gerald. “Thomas P. O’Neill.” World Book Encyclopedia. Volume 14. New York: World Book, 1992. 287.

“In Tip-Top Shape.” Time 26 January 1987: 18.

O’Neill, Thomas P. Man of the House. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Rosen, Arthur. “Tip O’Neill.” New Multimedia Encyclopedia. Groliers Multimedia, 1994. IBM CD-Rom.

Sennot, Charles. “The last words for Mr. Speaker.” Boston Globe 11 January 1994: 17(25).

Woodleif, Wayne. “Family and friends say farewell to Tip.” Boston Herald 11 January 1994: 4.