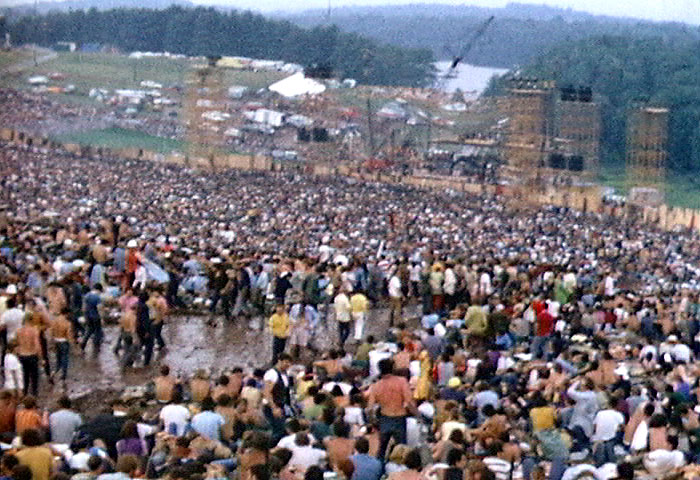

The muddiest four days in history were celebrated in a drug-induced haze in Sullivan County, New York (Tiber 1). Music soared through the air and into the ears of the more than 450,000 hippies that were crowded into Max Yasgur’s pasture. “What we had here was an once-in-a-lifetime occurrence,” said Bethel town historian Bert Feldmen. “Dickens said it first: ‘it was the best of times, it was the worst of times’. It’s an amalgam that will never be reproduced again” (Tiber 1). It also closed the New York State Thruway and created one of the nation’s worst traffic jams (Tiber 1). Woodstock, with its rocky beginnings, epitomized the culture of that era through music, drug use, and the thousands of hippies who attended, leaving behind a legacy for future generations. Woodstock was the hair brained idea of four men that met each other completely at random. It was the counterculture’s biggest bash, which ultimately cost over $2.4 million, and was sponsored by John Roberts, Joel Rosenman, Artie Kornfeld, and Michael Lang (Young 18).

John Roberts was an heir to a drugstore and toothpaste manufacturing fortune. He supplied the money, for he had a multi-million dollar trust  fund, a University of Pennsylvania degree, and a Lieutenant’s commission in the Army (Tiber 1). Joel Rosenman, the son of a prominent Long Island orthodontist, had just graduated from Yale Law School (Makower 28). In 1967, he was playing guitar for a lounge band in motels from Long Island to Law Vegas. He and Roberts met on a golf course in the fall of 1966 (Tiber 1). By the next winter, Roberts and Rosenman shared an apartment and were trying to figure out what to do with their lives. One idea was to create a screw ball situation comedy for television (Landy, Spirit 62). “It was an office comedy about two pals with more money than brains and a thirst for adventure,” Rosenman said. To get plot ideas for their sitcom, Roberts and Rosenman put a classified as in the Wall Street Journal and Fanning 2 the New York Times in March of 1968 that read: “Young men with unlimited capital looking for interesting, legitimate investment opportunities and business propositions” (Tiber 1). Artie Kornfeld was the vice-president of Capitol Records.

fund, a University of Pennsylvania degree, and a Lieutenant’s commission in the Army (Tiber 1). Joel Rosenman, the son of a prominent Long Island orthodontist, had just graduated from Yale Law School (Makower 28). In 1967, he was playing guitar for a lounge band in motels from Long Island to Law Vegas. He and Roberts met on a golf course in the fall of 1966 (Tiber 1). By the next winter, Roberts and Rosenman shared an apartment and were trying to figure out what to do with their lives. One idea was to create a screw ball situation comedy for television (Landy, Spirit 62). “It was an office comedy about two pals with more money than brains and a thirst for adventure,” Rosenman said. To get plot ideas for their sitcom, Roberts and Rosenman put a classified as in the Wall Street Journal and Fanning 2 the New York Times in March of 1968 that read: “Young men with unlimited capital looking for interesting, legitimate investment opportunities and business propositions” (Tiber 1). Artie Kornfeld was the vice-president of Capitol Records.

He smoked hash in the office and was the Company’s connection with the rockers that were starting to sell millions or records (Makower 32). Michael Lang’s friends described him as a “cosmic pixie” (Makower 33). He had a head full of curly black hair down to his shoulders. At 23, he owned what may have been the first head shop in the state of Florida. In 1968, Lang produced one of the biggest rock shows ever, the two-day Miami Pop Festival, which drew 40,000 people (Tiber 1). At 24, Lang was the manager of a rock group called Train. He took his proposal for a record deal to Kornfeld at Capitol, and history began. The four met to discuss their idea at a high-rise on 83rd Street (Young 37). Lang reminisces, “They were kind of preppy. Today, I guess they’d be yuppies” (Landy, Festival 29). The Woodstock Music and Art Fair was the name that they came up with. The four had decided to have a little party- inviting only rich stars that could afford the giant cover charge to gain entrance. By the end of their third meeting to discuss the event, the party had snowballed into a “bucolic concert for 50,000 people, the world’s biggest rock-n-roll show” (Obst 42). The four partners formed a corporation in March- Woodstock Ventures, Inc (Tiber 3). The Woodstock Ventures team scurried around to find a site (Makower 42). The 300-acre Mills Industrial Park in Wallkill, New York, would have been perfect, but Roberts interjected, “The vibes aren’t right here. This is an industrial park. We gotta have a site now” (Smith 28). Finally, Max Yasgur’s pasture in Sullivan County, appeared. He was a prominent dairy farmer, and was pleased to Fanning 3 receive that $10,000 to rent out his fields for 4 days (Tiber 1). The location had been chosen.

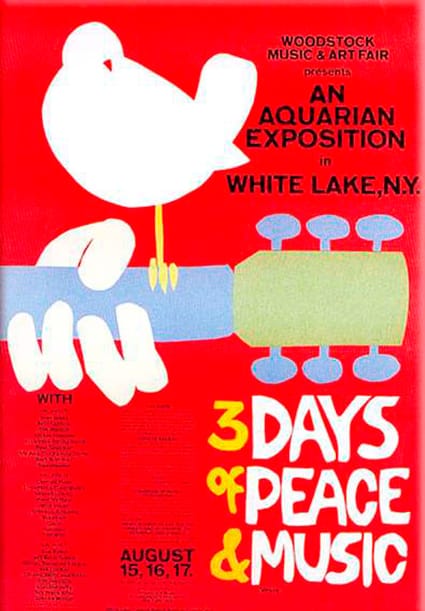

Now the fearless foursome was on to bigger and better things. “In the cultural-political atmosphere of 1969, Kornfeld and Lang knew it was important to pitch Woodstock in a way that would appeal to their peer’s sense of independence” (Tiber 3). By early April, the promoters were carefully cultivating news of Woodstock in publications such as the Village Voice and Rolling Stone. The group settled on the slogan “Three Days of Peace and Music” (Young 53). They figured that “peace” would link the anti-war sentiment to the concert (Young 53). The Woodstock dove is actually a catbird; originally, it perched on a flute (Tiber 4). “As soon as Ira Arnold (a copywriter on the Woodstock crew) called with the copy- approved ‘Three Days of Peace and Music,’ I just took a razor blade and cut that catbird out of the sketchpad I was using. First, it sat on a flute. I was listening to jazz at the time, and I guess that’s why. But anyway, it sat on a flute for a day, and I finally ended up putting it on a guitar” (Landy, Festival 60).

Advertising was coming along well, and the boys looked to the future for the bands to sign. Woodstock Ventures was trying to book the biggest rock-n-roll bands in America, but the bands were reluctant to sign with an untested company that might be unable to deliver (Obst 103). Ventures solved the problem by handing out rather hefty paychecks. The Jefferson Airplane received $12,000; they usually received $5-6,000 for a gig. Creedence Clearwater Revival signed for $11,500, The Who for $12,500. Most bands were signed for $5,000; Ventures offered twice that amount (Young 102). After a much-anticipated wait, Friday, August 15, 1969 arrived.

So many more people than expected came, and ticket sales ceased (Tiber 13). The traffic was so bad on all the roads Fanning 4

leading to Sullivan County, food, medicine and doctors, and the artists performing were flown in by helicopter to the concert-site. Woodstock organizers blamed the state police for the traffic jams. An expected turnout of 50,000-100,000 people turned into a ludicrous number of 200,000-400,000, bigger than the four original partners had ever expected (Landy, Spirit 45). On Friday, Joan Baez was the headliner, preceded by Tim Hardin, Arlo Gutherie, Sweetwater, the Incredible String Band, Ravi Shankar, Bert Sommer and Melanie, and Sly and the Family Stone. A no-name musician who was there for the show named Richie Havens was forced to go on first (Tiber 15). No other bands were there yet, and he had to play for two hours. Country Joe McDonald was another to play without prior notice. Bands still were not set up, so he played, with an acoustic guitar, songs like “Fish Cheer” and “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag” (Tiber 15). Finally, the other bands went on and were a success. The only band that producers were worried about was Sly and the Family Stone. They had a tendency to fire up small crowds and invite fans to rush the stage (Young 82). To remedy this problem, Artie Kornfeld and his wife got in the pit in front of the stage, between the fans and the performers.

Needless to say, there were no riots. Saturday’s bill included The Who, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the  Grateful Dead, Canned Heat, Mountain, and Santana (Landy, Spirit 123). For crowd control, the producers figured that music should be played consistently, so they had to bed and plead with Saturday’s acts to play sets twice as long as originally planned. Sunday’s line-up included The Band, Joe Cocker, Crosby, Stills, & Nash, Ten Years After, Johnny Winter, and Iron Butterfly. Jimi Hendrix was the headliner (Tiber 26). Fanning 5

Grateful Dead, Canned Heat, Mountain, and Santana (Landy, Spirit 123). For crowd control, the producers figured that music should be played consistently, so they had to bed and plead with Saturday’s acts to play sets twice as long as originally planned. Sunday’s line-up included The Band, Joe Cocker, Crosby, Stills, & Nash, Ten Years After, Johnny Winter, and Iron Butterfly. Jimi Hendrix was the headliner (Tiber 26). Fanning 5

Although he did not play until 9 am, Monday morning, he delivered an outstanding performance, including the “Star-Spangled Banner”, in honor of the War (Young 243). There were people everywhere. Tents were staked as far as the eye could see, the sweet smell of marijuana was in the air. Rain started to fall at around midnight, and people were swimming everywhere they could (Landy, Festival 14). Bert Feldman, the town historian, suddenly became Woodstock’s censor. He stood between television cameras and the swimming holes, because people only wore one or two garments. He later said, “you never saw a fight in there, though. You could argue, of course, that it was because everyone was stoned” (Tiber 15). There was a tent dubbed the Freak-Out Tent (Tiber 18) which in reality was the nurses’ station. A certain Nurse Sanderson presided over the tent, and her first patient kept screaming “SPID-ERS!!” She learned quickly that she had to deal with bad trips by physical stroking and soft words. The was getting paid only $50 a day, but she wanted to learn how to deal with new sicknesses associated with the drug culture (Young 203). People entered the Freak-Out Tent for three main reasons. The most famous was experiencing the imaginary symptoms of bad trips. The next was people with cut feet. The third was quite odd.

Sanderson said, “They had burned their eyes staring at the sun. If they were tripping, they’d lie down on their backs and just stare…” (Young 203). After the final hippie drudged out of Max Yasgur’s pasture, the problems for Woodstock Ventures began. Kornfeld’s promotional expenses were more then $150,000, 70 % over budget. Lang’s production expenses had soared to $2 million, more than 300 % over budget (Tiber 26). All in all, the total cost of Woodstock had been at least $2.4 million. A banker friend named Fanning 6

Charlie Price helped them out by loaning them the money with a fixed interest rate. The Roberts family paid off the debt themselves. Roberts’ father and brother told the Wall Street banker that they never had run out on debts and they weren’t going to start now (Young 234). Feelings of ill will lingered between the four, and it seemed that they went off two and two. Rosenman and Roberts stayed best friends, as did Kornfeld and Lang (Tiber 27). “The four men who had produced Woodstock were separated for more than 20 years by Woodstock’s fallout” (Tiber 27). For the next decade, Woodstock was virtually a cliché for all that was goofy and bad about the ’60’s (Obst 232). Trying to imitate the original, there was a concert dubbed “Woodstock II, the Re-union.” A quarter of a million revellers flocked to Saugerties, paying $150 for one ticket (Tiber 31). The original Woodstock ticket price was $18. There was also a Woodstock ’99, yet another frugal attempt to imitate the original (Tiber 31). It only ended in tragedy as riots broke out and people were killed. This proves that when something is done right the first time, it should not be imitated. In all, Woodstock had 5,162 medical cases, 797 instances of drug abuse, eight miscarriages, two deaths by drug overdose, and one accidental death by a young man getting run over by a tractor (Tiber 30). After a rocky beginning, Woodstock turned out to be the biggest concert in history (Tiber 2). It was three days of music and peace, a time that teenage hippies and burnouts could spend sleeping in fields listening to psychedelic music. A good time was had by all, and although it has been tried, perfection cannot be imitated.

WORKS CITED

Landon, Franklin. “The Big Woodstock Rock Trip.” Time 29 Aug. 1969: 14B-22.

Landy, Elliot. Woodstock Vision- The Spirit of a Generation. Chicago: Square Books, 1994.

—. Woodstock 1969: The First Festival. Chicago: Square Books, 1994.

Makower, Jeol. Woodstock: The Oral History. New York: Dolphin/Double Day, 1989.

Obst, Lynda R., and Robert Kingsbury. The Sixties. New York: Norton, 1977.

Smith, Carole. “The Woodstock Music Festival.” Goldmine 28 Aug. 1987: 28-78.

Tiber, Elliot. “How Woodstock Happened… Parts 1-5.” < http:// www. woodstock69.com.htm> (16 Jan. 2000).

Wharton, Samuel. “Woodstock Music Festival.” Life 29 Aug. 1969: 25-30.

“Woodstock, N. Y.” Compton’s Interactive Encyclopedia Deluxe. 1997 ed.

Young, Jean and Michael Long. Woodstock Festival Remembered. New York: Ballentine Books, 1979.