The Democrats nominated James Buchanan and John Breckenridge, the newly formed Republican party nominated John Fremont  and William Drayton, the American [or Know-Nothing] party nominated former president

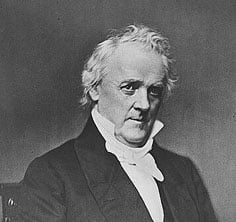

and William Drayton, the American [or Know-Nothing] party nominated former president  Millard Fillmore and Andrew Donelson, and the Abolition Party nominated Gerrit Smith and Samuel McFarland. Buchanan started his political career as a state representative in Pennsylvania, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1821, appointed minister to Russia in 1832, and elected US Senator in 1834. He was appointed Secretary of State in 1845 by President Polk and in that capacity helped forge the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War. He was appointed by President Polk as minister to Great Britain in 1853. As such, he, along with the American ministers to Spain and France, issued the Ostend Manifesto, which recommended the annexation of Cuba to the United States. This endeared him to southerners, who assumed Cuba would be a slave state.

Millard Fillmore and Andrew Donelson, and the Abolition Party nominated Gerrit Smith and Samuel McFarland. Buchanan started his political career as a state representative in Pennsylvania, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1821, appointed minister to Russia in 1832, and elected US Senator in 1834. He was appointed Secretary of State in 1845 by President Polk and in that capacity helped forge the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War. He was appointed by President Polk as minister to Great Britain in 1853. As such, he, along with the American ministers to Spain and France, issued the Ostend Manifesto, which recommended the annexation of Cuba to the United States. This endeared him to southerners, who assumed Cuba would be a slave state.

He was one of several northerners supported over the years by southern Democrats for being amenable to slaveholders’ interests, a situation originating with Martin van Buren. Buchanan’s two major rivals for the nomination, Franklin Pierce and Stephen Douglas, were both politically tainted by the bloodshed in Kansas. Buchanan was untainted, since he had been abroad during most of the controversy. Even so, he did not secure the nomination until the seventeenth ballot. Fremont was best known as an explorer and a war hero. He surveyed the land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, explored the Oregon Trail territories and crossed the Sierra Madres into the Sacramento Valley. As a captain in the Army, he returned to California and helped the settlers overthrow Mexican rule in what became known as the Bear Flag Revolution, a sidebar to the Mexican War. He was elected as one of California’s first two Senators. The infant Republican party was born from the ashes of the Whig party, which had suffered spontaneous combustion as a result of the slavery issue. The party’s convention was a farce; only northern states and a few border slave states sent delegates. Sticking to their Whig roots, they nominated a war hero, albeit a minor one. William Drayton’s runner-up for the VP slot was Abraham Lincoln. Fillmore, having been the thirteenth president following the death of Zachary Taylor, found himself representing the American party after many northern delegates left the convention over a rift caused by the slavery issue. Their objection was that the party platform was not strong enough against the spread of slavery. The party’s vice presidential nominee was a nephew of Andrew Jackson and the editor of the Washington Union. The party, also known as the Know-Nothings, was extremely antagonistic towards immigrants, Catholics and other assorted minorities. The party was born in 1850, when several covert “Native American” societies joined together, their secret password being “I know nothing.” Smith was nominated by the Abolition party in New York, which had nominated Frederick Douglass for New York secretary of state the year before under the label New York Liberty Party. The Campaign: Neither Buchanan nor Fremont campaigned themselves. Republicans declared Buchanan dead of lockjaw. Fremont, however, had a splendid campaign substitute, his beautiful wife Jessie, prompting “Oh Jessie!” campaign buttons. The Democrats tried desperately to avoid the slavery issue altogether, opting instead to pursue the conservative effort to preserve the Union. The Republicans, on the other hand, actively attacked slavery. Their campaign slogan was “Free Soil, Free Men, Freedom, Fremont”. [Shields-West, pgs 78 & 80] The self-serving efforts of Stephen Douglas did more to mold the campaign of 1856 than did any other single event.

Although he did not intentionally destroy the North-South balance created by the Compromise of 1850, his focused quest for the  White House caused him to make some foolish choices. Douglas coveted a rail head in Chicago for the new transcontinental railroad. This would make Chicago a major trade center for the country, not unlike New York City when the Erie Canal was completed. He knew increased economic power for his home state would translate as increased political power for him. The South, on the other hand, wanted the rail head located in St. Louis, or even New Orleans. In order to secure southern support for his plan, Douglas chose to win them over by proposing the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a bill that would divide the Nebraska Territory into two separate territories, each having popular sovereignty. This would amount to nullification of the Missouri Compromise. Using the power of his new southern allies, Douglas wheeled and dealed the Kansas-Nebraska Act through Congress. By doing so, Douglas alienated his northern colleagues. The anti-slavery movement had become a formidable force in northern politics. Douglas mistakenly believed popular sovereignty had become more acceptable to the general public than it actually had. In July of 1856, ‘Conscience Whigs”, northern Democrats and Free Soilers met in Jackson, Michigan, to form the Republican party for the specific purpose of opposing slavery. In the meantime, pro-slavery factions, many from across the Missouri border, held a bogus election in the newly formed Kansas Territory, adopting a pro-slavery constitution and electing a pro-slavery state government. When anti-slavery citizens learned what had happened, they organized their own elections. President Pierce, in a serious error of judgement, recognized the first government as the official one, prompting widespread bloodshed throughout the territory. This new territory, born of such dubious beginnings, became known as “Bleeding Kansas”. Pierce and Douglas, from that moment forward, would be scarred politically. Buchanan ultimately won the election in the electoral college, although he did not garner a popular majority. It was an uneasy victory, with sectionalism clearly present in the vote tallies. Normally, a period of relative calm follows a presidential election, but the political rhetoric of this campaign and the unrelenting tension between the North and the South would not allow it. On December 1, Pierce sent a bitter and highly partisan message to Congress. He pointedly blamed the continuing Kansas problems on northern propogandists and outside “agents of disorder”. He accused the Republicans of preparing the country for civil war. Many in Congress were understandably outraged, reversing the charges of sectionalism right back at Pierce. Some blamed the Kansas situation directly on the outgoing president. In all, it was an unnecessarily unmagnanimous annual message. The Buchanan Presidency: In their attempt to find a non-controversial presidential candidate, the Democrats instead found themselves with a weak president. Buchanan tried to appease both sides by appointing a mix of northern and southern politicians to his cabinet, but each side accused him of favoring the other for the important positions.

White House caused him to make some foolish choices. Douglas coveted a rail head in Chicago for the new transcontinental railroad. This would make Chicago a major trade center for the country, not unlike New York City when the Erie Canal was completed. He knew increased economic power for his home state would translate as increased political power for him. The South, on the other hand, wanted the rail head located in St. Louis, or even New Orleans. In order to secure southern support for his plan, Douglas chose to win them over by proposing the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a bill that would divide the Nebraska Territory into two separate territories, each having popular sovereignty. This would amount to nullification of the Missouri Compromise. Using the power of his new southern allies, Douglas wheeled and dealed the Kansas-Nebraska Act through Congress. By doing so, Douglas alienated his northern colleagues. The anti-slavery movement had become a formidable force in northern politics. Douglas mistakenly believed popular sovereignty had become more acceptable to the general public than it actually had. In July of 1856, ‘Conscience Whigs”, northern Democrats and Free Soilers met in Jackson, Michigan, to form the Republican party for the specific purpose of opposing slavery. In the meantime, pro-slavery factions, many from across the Missouri border, held a bogus election in the newly formed Kansas Territory, adopting a pro-slavery constitution and electing a pro-slavery state government. When anti-slavery citizens learned what had happened, they organized their own elections. President Pierce, in a serious error of judgement, recognized the first government as the official one, prompting widespread bloodshed throughout the territory. This new territory, born of such dubious beginnings, became known as “Bleeding Kansas”. Pierce and Douglas, from that moment forward, would be scarred politically. Buchanan ultimately won the election in the electoral college, although he did not garner a popular majority. It was an uneasy victory, with sectionalism clearly present in the vote tallies. Normally, a period of relative calm follows a presidential election, but the political rhetoric of this campaign and the unrelenting tension between the North and the South would not allow it. On December 1, Pierce sent a bitter and highly partisan message to Congress. He pointedly blamed the continuing Kansas problems on northern propogandists and outside “agents of disorder”. He accused the Republicans of preparing the country for civil war. Many in Congress were understandably outraged, reversing the charges of sectionalism right back at Pierce. Some blamed the Kansas situation directly on the outgoing president. In all, it was an unnecessarily unmagnanimous annual message. The Buchanan Presidency: In their attempt to find a non-controversial presidential candidate, the Democrats instead found themselves with a weak president. Buchanan tried to appease both sides by appointing a mix of northern and southern politicians to his cabinet, but each side accused him of favoring the other for the important positions.

Buchanan never married, so the social duties of the White House were handled by his niece, Harriet Lane. During a state visit by the Prince of Wales, an orchestra performed the premiere of a new song dedicated to Miss Lane, titled “Listen to the Mockingbird.” [Saturday Evening Post, pg 57] Two significant events took place shortly after Buchanan’s inauguration, both of them having a terrible affect upon the nation and neither one attributable to Buchanan. Two days after taking office, the Taney supreme court handed down its infamous Dred Scott decision, or rather non-decision. The supreme court basically decided that slaves were property and, therefore, had no rights in the court system. The court cited the Fifth Amendment in refusing to meddle in disputes involving slaves. In the larger sense, though, the ruling declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. Buchanan supported the decision. The second event was the Panic of 1857. Though not as severe as the Panic of 1837, it did cause widespread unemployment. A drop in crop exports to Europe, caused by the unexpected end to the Crimean War, caused a glut on the US market with corresponding price drops. Bank failures led the way, starting with the Ohio Life Insurance & Trust Company, which was actually one of the most respected financial institutions in the country. Lack of specie on hand led to many more bank closures. Secretary of the Treasury Cobb had another $4 million in gold coins minted to increase the supply, but the effort was fruitless. [Stampp, pgs 223-4] The industrialized Northeast was hardest hit by the depression and northern manufacturers and bankers naturally blamed southern Democrats. Sectionalism continued to worsen. The Kansas controversy continued to plague the Buchanan administration. He favored the admission of Kansas as a slave state. The territorial government [the pro-slavery one recognized by Pierce] held a statehood constitutional convention in Lecompton, which anti-slavery factions refused to recognize. As a result, the pro-slavery forces won control with only about ten percent voter participation. Anti-slavery forces regained control of the territorial legislature in the next election and voted down the document. [Brinkley, pg 375] Buchanan, against clear evidence to the contrary, decided to side with the Lecompton proposal. Stephen Douglas, in another bizarre moment of political suicide, argued against the Lecompton document. The statehood constitution was ultimately submitted to the general population of Kansas, who overwhelmingly defeated the illegitimate document. However, Kansas was not admitted to the union, as a free state, until the closing days of the Buchanan administration. By then several southern states had already seceded. Buchanan had failed.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergman, Peter M. The Chronological History of the Negro in America. New York: Harper & Row, 1969.

Black, Earl and Black, Merle. The Vital South: How Presidents Are Elected. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Brinkley, Alan. American History, A Survey, Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

Meltzer, Milton. Milestones to American Liberty: the Foundations of the Republic. New York: Cromwell, 1961. Saturday Evening Post. The Presidents. Indianapolis: Curtis Publishing, 1980.