Shortly after Charles Lindbergh landed, he was swarmed by 25, 000 Parisians who carried the wearied pilot on their shoulders. They were rejoicing that Charles Lindbergh, the American aviator who flew the first transatlantic flight, had just landed at Le Bourget field in France. Having just completed what some people called an impossible feat, he was instantly a well-known international hero. Despite his pro-German stance during World War II, Charles Lindbergh is also an American hero. A record of his happiness and success exists in the material form of his plane hanging in the Smithsonian Institute; however, much of Lindbergh’s life was clouded by turmoil. The life of Charles Lindbergh though best remembered for his heroic flight across the Atlantic, was marred by the kidnapping of his baby and his fall from favor with the American public following his pro-German stance during the 1930’s.

Charles Lindbergh, the famous American aviator, was born February 4, 1902 in Detroit, Michigan. As a boy he loved the outdoors and  frequently hunted. He maintained a good relationship with his parents “who trusted him and viewed him as a very responsible child”. His father, for whom young Charles chauffeured as a child, served in the U.S. Congress from 1907 to 1917. Lindbergh’s love of machinery was evident by the age of 14; “He could take apart an automobile engine and repair it”. Attending the University of Wisconsin, Lindbergh studied engineering for two years. Although he was an excellent student, his real interest was in flying. As a result, in 1922 he switched to aviation school. Planes became a center of his life after his first flight. His early flying career involved flying stunt planes at fair and air shows. Later, in 1925 he piloted the U. S. Mail route from St. Louis to Chicago. On one occasion while flying this route his engine failed and he did a nosedive towards the ground. Recovering from the nosedive he straightened the plane successfully and landed the plane unharmed. This skill would later be invaluable when he was forced to skim ten feet above the waves during his famous transatlantic flight.

frequently hunted. He maintained a good relationship with his parents “who trusted him and viewed him as a very responsible child”. His father, for whom young Charles chauffeured as a child, served in the U.S. Congress from 1907 to 1917. Lindbergh’s love of machinery was evident by the age of 14; “He could take apart an automobile engine and repair it”. Attending the University of Wisconsin, Lindbergh studied engineering for two years. Although he was an excellent student, his real interest was in flying. As a result, in 1922 he switched to aviation school. Planes became a center of his life after his first flight. His early flying career involved flying stunt planes at fair and air shows. Later, in 1925 he piloted the U. S. Mail route from St. Louis to Chicago. On one occasion while flying this route his engine failed and he did a nosedive towards the ground. Recovering from the nosedive he straightened the plane successfully and landed the plane unharmed. This skill would later be invaluable when he was forced to skim ten feet above the waves during his famous transatlantic flight.

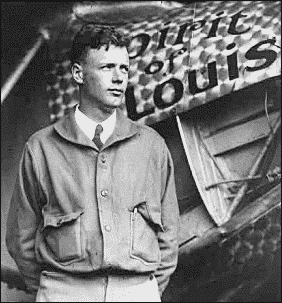

As early as 1919 Lindbergh was aware of a prize being offered by the Franco-American philanthropist Raymond B. Orteig of New York City. Orteig offered 25, 000 dollars to the individual who completed the first non-stop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris. Ryan Air manufactured his single engine monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, so named because many of his investors were from that city. In preparation for the flight, Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis from Ryan Airfield in St. Louis, non-stop to Roosevelt Field outside New York City. After arriving he waited six days to begin his flight to Paris, due to inclement weather.Although he was scheduled to attend the ballet on the evening of May 19, 1927, word came from the airfield that there was a large break in the weather coming across the Atlantic and that he was clear to fly first thing in the morning. As a precaution Lindbergh instructed one of his friends to stand guard outside the room where Lindbergh attempted to sleep that night. Unfortunately, with all the thoughts going through his head, sleep was an impossibility. Rising at 4:00 am, accompanied by a police escort, Lindbergh was driven to Roosevelt Field. Dressed in a brown flight suit complete with headpiece and goggles, Lindbergh climbed into his single engine monoplane and began his destiny with history; the first non-stop transatlantic flight.

During the flight of 33 hours and 32 minutes, Lindbergh ate five chicken sandwiches and consumed a one-liter bottle of water. It is not documented what Lindbergh did to occupy his time during the flight, but it is obvious based upon the length of the flight that staying awake must have been a major concern. In a famous film recounting this flight, speculation was that Lindbergh stayed awake by watching the activity of a housefly trapped in the cabin. Later, based upon his excess fuel level, Lindbergh considered continuing his flight to Rome, despite the fact that he had already traveled 5,800 km. Fearing it was too dangerous, he opted to land in Paris as planned. When Lindbergh approached Le Bourget Airport near Paris he noticed the headlights of many cars. Amazed that so many Parisians had come out to the field to greet him, Lindbergh anxiously deplaned. In their excitement some of the crowd tore pieces of the plane’s outer shell off as souvenirs. “Lindbergh’s achievement won the enthusiasm and acclaim of the world, and he was greeted as a hero in Europe and the U.S.”

Lindbergh, the American hero, was sent home on a naval vessel specially chartered by Harry S. Truman. When Lindbergh arrived in New York City he was greeted by a hero’s ticker tape parade in downtown New York City. Roughly 6 tons of confetti was thrown into the street in celebration of his historic flight. When the parade ended, Lindbergh was presented with an honorary key to the city of New York. Similar ceremonies were repeated in several U.S. and European cities. Later Lindbergh was commissioned as a colonel in the U.S. Air Service Reserve and served as a technical advisor for several commercial airlines. When in the service of one of the airlines, Lindbergh flew to Mexico and met the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico’s daughter, Anne Morrow. Soon began a very private relationship, resulting in their marriage in May of 1929. Though certainly a happy time in their life, this relationship would produce a child, one that would be brutally murdered.

The Lindbergh’s first son, Charles Augustus, was born in 1930. Living outside New York City, they moved to a rural community near Hopewell,  New Jersey. Far away from the crime of a major city, the Lindberghs were comfortable in this small community. Soon, that would end with the kidnapping of their son. Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was kidnapped about 9:00p.m. on March 1, 1932 , abducted from the nursery on the second floor of the Lindbergh’s home. At about 10:00p.m, the child’s nurse, Betty Gow, found that the baby was not in the nursery. The grounds around the house were searched and a ransom note demanding 50,000 dollars was found. The New Jersey State Police took charge of the Investigation. A second ransom note was given to Lindbergh on March 6, 1932, stating that the kidnappers now wanted 70,000 dollars. A third ransom note given to Lindbergh on March 8, dictated that a negotiator proposed by the Lindbergh’s was not acceptable and that Dr. John F. Condon, a retired school principal, was suitable. Negotiations for the ransom money took place in the Bronx Home News newspaper columns using the code name “Jafsie.” Dr. Condon eventually met with the kidnappers and they negotiated until the kidnappers brought the ransom demand down to 50,000. Charles gave Dr. Condon $50,000 in cash, which he was instructed to give to the kidnappers. Having done so, Dr. Condon was told that the baby was in a boat called “Nellie” in Martha’s vineyard. Lindbergh and the police searched Martha’s Vineyard and found nothing. On May 12, 1932 the baby’s body was accidentally found, partially buried and heavily decomposed. The body was about four and a half miles southeast of the Lindbergh home. William Allen, an assistant on a truck driven by Orville Wilson, found the body. The baby’s head was crushed, there was a hole in the skull and some of the body parts were missing. The body was identified and cremated at Trenton, New Jersey, on May 13, 1932. The baby had been dead for two months and the death was due to the blow to the head. Bruno Hauptmann a German born carpenter was convicted of the kidnapping. Hauptmann was later sentenced to death and died in the Electric Chair. After this incident Congress enacted “Lindbergh Law” which stated that kidnapping was now a federal crime. With all of the publicity that came with the trial the Lindbergh’s were distraught. They decided the best thing to do would be to move to England. Lindbergh, though the American hero, was not happy with his life in America. He and his wife chose a life of seclusion in Europe.

New Jersey. Far away from the crime of a major city, the Lindberghs were comfortable in this small community. Soon, that would end with the kidnapping of their son. Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was kidnapped about 9:00p.m. on March 1, 1932 , abducted from the nursery on the second floor of the Lindbergh’s home. At about 10:00p.m, the child’s nurse, Betty Gow, found that the baby was not in the nursery. The grounds around the house were searched and a ransom note demanding 50,000 dollars was found. The New Jersey State Police took charge of the Investigation. A second ransom note was given to Lindbergh on March 6, 1932, stating that the kidnappers now wanted 70,000 dollars. A third ransom note given to Lindbergh on March 8, dictated that a negotiator proposed by the Lindbergh’s was not acceptable and that Dr. John F. Condon, a retired school principal, was suitable. Negotiations for the ransom money took place in the Bronx Home News newspaper columns using the code name “Jafsie.” Dr. Condon eventually met with the kidnappers and they negotiated until the kidnappers brought the ransom demand down to 50,000. Charles gave Dr. Condon $50,000 in cash, which he was instructed to give to the kidnappers. Having done so, Dr. Condon was told that the baby was in a boat called “Nellie” in Martha’s vineyard. Lindbergh and the police searched Martha’s Vineyard and found nothing. On May 12, 1932 the baby’s body was accidentally found, partially buried and heavily decomposed. The body was about four and a half miles southeast of the Lindbergh home. William Allen, an assistant on a truck driven by Orville Wilson, found the body. The baby’s head was crushed, there was a hole in the skull and some of the body parts were missing. The body was identified and cremated at Trenton, New Jersey, on May 13, 1932. The baby had been dead for two months and the death was due to the blow to the head. Bruno Hauptmann a German born carpenter was convicted of the kidnapping. Hauptmann was later sentenced to death and died in the Electric Chair. After this incident Congress enacted “Lindbergh Law” which stated that kidnapping was now a federal crime. With all of the publicity that came with the trial the Lindbergh’s were distraught. They decided the best thing to do would be to move to England. Lindbergh, though the American hero, was not happy with his life in America. He and his wife chose a life of seclusion in Europe.

In 1935 the Lindbergh’s packed their belongings and moved to the rural countryside of England. There, while living a life of semi-retirement, Lindbergh studied the possibility of creating an artificial heart pump, as inspired by the French surgeon Alexis Carrel. Lindbergh’s and Carrel’s experimentation did not result in a functioning model, even though their first experiments appeared to be very successful. Following two years of failure to complete their task, the two gave up. They did however eventually co-author the book, The Culture of Organs (1938). During this time, Lindbergh turns his sights to another task, the evaluation of the German Luftwaffe.

At the request of the U.S. government, Lindbergh was asked to evaluate the German Air Force. Well respected by the Germans, Lindbergh was shown most of the German Air Force and even the new planes. Hitler wanted Lindbergh to see the extent of his air force and hoped that Lindbergh would reveal to officials in London and Washington the power of the Germans. Meanwhile, Lindbergh informed the U.S. government of all that he had seen, including the fact that he was very impressed with the German Air Force. Hitler was very grateful to Lindbergh for the time that he spent evaluating the German Air Force. To commemorate his work, Lindbergh was decorated by Adolph Hitler in 1938. Lindbergh gratefully accepted the honor, and act for which he was widely criticized. Lindbergh even considered moving to Germany because he considered the German civilization advanced to that of the rest of Europe. Although he never really understood the holocaust and what was happening in Germany at the time, Lindbergh never recants this view of Germany and the German people. Lindbergh never returned the medal given to him by Hitler, which further alienated him from the American public. Lindbergh, once the American hero, is now considered by many to be a traitor.

Lindbergh returned to the U.S. in 1939 and began a series of antiwar speeches. Lindbergh believed that it was not the US war to fight and that  if the US got involved it would lose. Lindbergh toured the country speaking to large audiences and ended up being widely criticized for his views. Lindbergh was labeled as pro-German and pro-nazi. He had to resign his commission in the US Air Corps Reserve and his membership in the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Lindbergh still considered himself a loyal American and wanted to participate.

if the US got involved it would lose. Lindbergh toured the country speaking to large audiences and ended up being widely criticized for his views. Lindbergh was labeled as pro-German and pro-nazi. He had to resign his commission in the US Air Corps Reserve and his membership in the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Lindbergh still considered himself a loyal American and wanted to participate.

During World War II, Lindbergh wanted to help out the war effort but was not permitted, based upon his pro-German stance. Eventually he found a way. He served as a civilian consultant for an aircraft maker in the Pacific. Lindbergh had a desire to fly bombers against the Japanese but his supervisors would not let him. With his persuasive personality Lindbergh convinced his supervisors to let him fly some combat missions against the Japanese. Eventually Lindbergh flew more than 55 missions against the Japanese. Later, he recounted these exploits in a book entitled The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. Following the end of the war, Lindbergh and his wife continued their life of seclusion but elected to live in a remote section of a United States territory.

Lindbergh decided that he would like to live the remainder of his life in Maui, Hawaii. Earlier, a friend of Lindbergh’s accompanied him to Hawaii. Lindbergh was so impressed with the island, that he decided it was truly a paradise, one of the best places he had ever visited. That same friend offered to sell him several acres in Maui, which Lindbergh gratefully accepted. Charles and Anne built a simple home there to serve as their island retreat. Lindbergh still enjoyed the outdoors and his home close to the wilderness. The Lindbergh’s started spending six to eight weeks a year at their home in Maui and as time went on they increased the time spent there. Eventually, Lindbergh was diagnosed with an incurable cancer. In 1974 Lindbergh flew from a New York Hospital to Hana, Maui, to spend his last days with his family on the island he had grown to love. His funeral was a simple one, consisting of a Eucalyptus coffin carried in a local pickup truck serving as a hearse. Lindbergh, the great American hero, was laid to rest on American soil but far from the American public who had turned against him.

In conclusion, the life of Charles Lindbergh though best remembered for the heroic flight across the Atlantic, is marred by the kidnapping of his baby and his fall from favor with the American public following, his pro-German stance during the 1930’s.