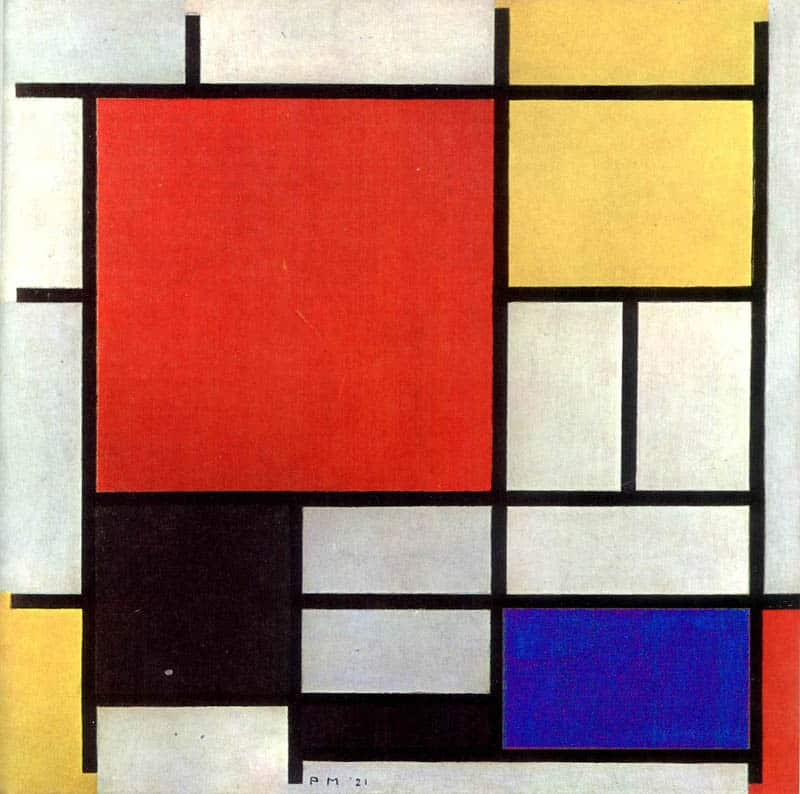

De-Stijl(The Style), also called ” Neoplasticism” is recognizable by the use of straight horizontal and vertical lines as well as the use of the primary colors red, yellow and blue. They also used the colors black, white and gray. It is a style that went back to the fundamental elements of the art: color and form, level and line. With these elements, the artist developed a new sculptural language and with that placed the ideal world opposite the reality.

Most of the artists used closed and open forms, density and space, color and form. But using these elements within one painting, the ideal harmony could be reached. All the elements have their own function in totality.

The lines are the borders and make the open or closed forms. The lines are also used to create a certain space. The border of the painting is not the end of the painting. By using only the primary colors, the artist could create a 3-dimensional effect. The colors attract immediate attention and the rest of the painting seems to go to the background. It looks like the white forms are further back than the colored forms. Therefore, the artists created a front and a back in their paintings.

The Development of De Stijl

The De Stijl movement was started in the Netherlands from 1917 to 1931. The founder, Theo van Doesburg started a group which was an association of painter Piet Mondrian, Bart van der Leck, and Vilmos Huszar, the architect Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, the poet and essayist Antony Kok and other artists.

Theo van Doesburg applied De Stijl principles to architecture, sculpture and typography. He edited and published the journal “De Stijl” from 1917 until his death in 1931. This publication spread the movement’s theory and philosophy to a large audience. De Stijl advocated the absorption of pure art by applied art.

In the late 1910s, paintings by Mondrian, Burt van der Leck and van Doesburg were indistinguishable. These artists used primary colors, red yellow and blue with black, gray and white, straight horizontal and vertical lines, and flat planes limited to rectangles and squares. With their visual art form, De Stijl artists believed beauty arouse from the absolute purity of the work.

They explained how they aimed to bring about the purification of different fields of the arts by searching for the most fundamental elements of each separate field of art and then uniting these elements in a well-balanced relationship. Therefore, the content of their work then became universal harmony, the order that pervades throughout the universe. This attitude was widespread during World War I.

One of the most important factors in the development of De Stijl was the neutrality of Holland during the First World War. In 1929, Theo van Doesburg wrote” Though there was no war in our neutral Netherlands, yet the war outside caused commotion and a spiritual tension…This war, raging at our borders, drove home many artists who had been working abroad.

Such as Van der Leck hurried home from a trip to Morocco, and Mondrian, who had come from Paris to visit his ill father, was forced to remain in Holland for the duration of the war…”

At that time it was very confused in Holland. The people wanted peace, rest and harmony again. The members of De-stijl tried to reflect in their work what in the entire social development could not be achieved, “the Ideal Harmony”. In 1932, Mondrian wrote” It was a painful time, the time of the Great War, in Holland as well…In spite of everything, in Holland, there still existed the possibility of being preoccupied with purely ethical questions.

Thus art continued there, developed there and what is particularly remarkable, is that it was only possible for it to continue in the same way as before the war. At this time only in neutral Switzerland (Dadaism) and revolutionary Russia (Suprematism and Constructivism) was there a similar co-operative development. These three movements: De Stijl, Constructivism and Dadaism, were later to come together and interact during the early twentieth-century art, architecture and design.

The Beginning

At the outbreak of war, during the period of military service, Theo van Doesburg started the idea of a group or association of artists and architects and a periodical in which they could express their views. Here he met the poet and essayist Antony Kok, who was to be one of the founder members of De Stijl. In 1915, van Doesburg had contacted Oud and Mondrian, and they discussed the idea of a magazine. In early 1917, van Doesburg visited Mondrian and van der Leck who were both living at Laren, near Amsterdam, and tried to earn their support–van Doesburg had for some time been an admirer of Mondrian’s work.

Mondrian’s main contribution to the development of De Stijl was the series of ‘plus and minus’ paintings from 1914 to 1917. These are sometimes known also as ‘pier and ocean’ paintings because there inspired by the sea and pier at Scheveningen.

Van Doesburg sees the expressive means of all the arts as relationships between positive and negative elements. In music, sounds (positive) and silence (negative); in painting, color (positive) and non-color–black, white and grey–(negative); in architecture, plane and mass (positive) and space (negative).

In 1917 the first issue of the magazine “De-stijl” was published. The idea for this magazine came from Theo van Doesburg. It was meant for explaining his own work as well as the work of the other members of the alliance. For them, the magazine was an instrument to discuss new modern art to spread their own ideas.

During the years when De Stijl was published, there was not one signal exhibition in which all the members participated. All the members of De Stijl kept in touch mainly by mail, and mainly through van Doesburg, who is the sole editor for this magazine. Therefore, the artists of De Stijl knew one another’s work and ideas From De Stijl.

The Transformation

In 1919, both van Doesburg and Mondrian began to divide their canvases into small squares which were then used as the modules for asymmetric compositions. In 1920, Mondrian adopted a rather freer style of arranging flat rectangles of subdued primary colour and grays, whereas van Doesburg continued with his modular compositions until his introduction of the diagonal around 1924.

The Split

Around 1922, several artists of De Stijl had already withdrawn, mostly after difficulties with van Doesburg. In 1922, there was a split in the inner circle of De Stijl, between van Doesburg and Oud. In the same year, the differences between van Doesburg and Mondrian that were to lead Mondrian’s resignation surfaced for the first time. Due to van Doesburg developed his theory of elementary, which declared the diagonal to be a more dynamic compositional principle than horizontal and vertical construction, Mondrian stopped contributing articles to the journal in 1924. Therefore, a basic distinction can be made between De Stijl in the period before 1922.

The End

De Stijl ended in 1931 when Theo van Doesburg started a new magazine, called “Abstraction-Creation”. That is the end of his membership of De Stijl, and the magazine “De Stijl” died as well. However, De Stijl, this new art style did not end completely. In some way, the other artists continued carrying out the principles of De Stijl, but individually instead of as a group.

Piet Mondrian

Piet Mondrian was born on 7 March, 1872, at Amersfoort, Holland. He showed an art talent at his early age, but his parents expected him to prepare for a more conventional career than that of an artist. He met this requirement by enrolling in a program leading to a degree in art education.

In 1892, he taught drawing lessons for secondary education. While he was giving these lessons, he attended evening-classes himself at the Rijksacademy in Amsterdam, Holland. Mondrian painted a lot during this period. His work from this period is mostly naturalistic and impressionistic.

In his autobiographical essay of 1942 Mondrian acknowledges that he was strongly influenced by the work of Picasso. In 1912, he moved to Paris, and from that time his paintings began to show the marks of the new trend. The colour scale in his paintings is reduced to shades of yellow, ocher, and brown, with a few accents in blue or green. His canvases of this “cubism” period are cubist abstractions. Mondrian also reduced the diversity of natural forms to a framework of pictorial signs.

Gradually the curved lines and the obtuse or acute angles disappear from his compositions, and all that is left is a grid of horizontal and vertical lines, still broken here and thereby a few diagonals. Slowly he subdues simplifies his color spectrum as well; the intermediate tones, such as gray and brown vanish gradually. In 1918, Mondrian no longer made up a composition from separate color planes against a solid background; now he divided the canvas into compartments with a pattern of horizontal and vertical lines and filled the compartments with different colours.

With this extremely limited arsenal of pictorial means, the painters of De Stijl aimed at presenting “the true vision of reality”: an image of reality that should be independent of the accident’s momentary perception and likewise of the arbitrariness of the individual temperament of the artist. The objectivity that Mondrian had sought for so long seemed now to be within reach.

Mondrian spent all the years of his sojourn in Paris from 1919 to 1938, perfecting this style. Every painting he finished became the starting point for the next one. His pictures constantly grew purer and more radiant; the harmony he expressed in them became even simpler and more powerful. In 1925, Mondrian’s lozenge-shaped paintings appeared in answer to van Doesburg’s attempt to use the diagonal. In the same year, because of van Doesburg’s “deviation” from the principles of De Stijl, Mondrian left the group but remained faithful to his own style.

Mondrian moved to America in 1940, in his sixty-eight year, that his art once more underwent a renewal. In the late works in New York, the black lines are replaced by colored bands or by a rhythmic sequence of little blocks of colour; the calm, contained rhythm of the canvases goes gradually over into rapid staccato flashes, into a powerful, dynamic movement.

Mondrain’s creative powers were renewed and inspired by the invigorating impact of metropolitan New York, by the quick rhythms of the new dances, and above all by the certainty of victory over tyranny. But before he could complete his masterpiece in a new manner, Victory Boogie-Woogie, a sparkling, twinkling dance of colors, Mondrian died in New York, five weeks before his seventy-second birthday.

Naturally, Mondrian and De Stijl exerted a considerable influence in the Netherlands. They also made an impact throughout the Western world. The De Stijl group had a term to designate spirit of their age, a spirit to which Mondrian and his friends always attached great importance and in which their art was consciously rooted.

That term, which keeps recurring in the writings, was” the general consciousness of the time. ” In the earliest of several De Stijl manifestoes, published in the November 1918 issue and signed by nearly all the members, including Mondrian, this term is emphasized for the first time: “There is an old and a new consciousness of time. The old is connected with the individual.

The new is connected with the universal. The struggle of the individual against the universal is revealing itself in the world war as well as in the present day.” Mondrian always regarded the striving for generalization, for a suprapersonal culture, as a characteristic of his age.