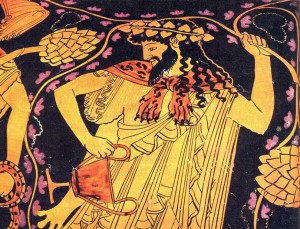

Dionysus was the most widely worshipped and popular god in ancient Greece. It’s not difficult to see why; he was their god of wine, merriment, ritual dance, warm moisture, and later, civilization. He was often depicted as a handsome young man, dressed in fawnskin, and carrying a goblet and an ivy-covered staff.

Some myths hold that Dionysus was the son of Zeus–the king of the god–and Persephone–queen of the underworld–but most myths state  that he is the son of Zeus and a mortal woman named Semel. This woman Semele was not any mortal, though. She was a princess, and a beautiful one at that. Zeus was notorious for being rather prolific, and when his wife, the goddess Hera heard that he had gone off and mated with a mortal, she became quite upset. Hera, in an attempt to exact her revenge, appeared to Semele and told her to ask Zeus to appear to her in his divine form. When Zeus obliged, Semele was immediately consumed in flames, for no mortal can look upon a god in his natural state. However, Zeus saved the unborn Dionysus by sewing him up in his thigh, thus incubating him.

that he is the son of Zeus and a mortal woman named Semel. This woman Semele was not any mortal, though. She was a princess, and a beautiful one at that. Zeus was notorious for being rather prolific, and when his wife, the goddess Hera heard that he had gone off and mated with a mortal, she became quite upset. Hera, in an attempt to exact her revenge, appeared to Semele and told her to ask Zeus to appear to her in his divine form. When Zeus obliged, Semele was immediately consumed in flames, for no mortal can look upon a god in his natural state. However, Zeus saved the unborn Dionysus by sewing him up in his thigh, thus incubating him.

What happened next is different in every story. Some myths say he lived with a king and queen loyal to Zeus until Hera discovered him, and, in a jealous rage, warped their brains. In this version of the story, Dionysus was turned into a goat by his father in an attempt to hide him from Hera; from then on he had small horns on his head.

After he was safe, he went to live with the nymphs, who taught him to make wine. Hera eventually found him again, and this time she also warped his brain. The nymphs rejected him, and he went to live with the satyrs, who were men with goat legs and horns, and their leader Silenus. Dionysus traveled with the satyrs, who disgusted everyone they encountered with their rude, drunken behavior.

Silenus is usually portrayed as a fat drunken man who rides on an ass. He was once captured by King Midas. When Dionysus intervened, Midas freed Silenus in exchange for the power to turn all he touched into gold. Dionysus and his band eventually encountered the maenads. The maenads were a group of wild, warlike creatures. They were horribly vicious, and unfortunately, they were also incredibly stupid. They started quite a few unsuccessful wars against kingdoms in Africa.

When Zeus finally found Dionysus again, he returned his mind to normal. However, Dionysus refused to give up his unruly traveling  companions. The people of Achaea loved Dionysus, but hated his satyr and maenad friends. One time, when Dionysus was visiting a port city, he was captured by a group of pirates who weren’t aware of his divine powers. He destroyed the pirates and sailed their ship to the Island of Naxos. It was there that he met his bride and only love Ariadne. Dionysus then made a journey into the depths of Hades to bring back his mother Semele. He took her to Mt. Olympus, and changed her name to Thyone. This fooled Hera, and Semele managed to remain safe. It was at this time that Dionysus was thought to have fully returned to his godly state.

companions. The people of Achaea loved Dionysus, but hated his satyr and maenad friends. One time, when Dionysus was visiting a port city, he was captured by a group of pirates who weren’t aware of his divine powers. He destroyed the pirates and sailed their ship to the Island of Naxos. It was there that he met his bride and only love Ariadne. Dionysus then made a journey into the depths of Hades to bring back his mother Semele. He took her to Mt. Olympus, and changed her name to Thyone. This fooled Hera, and Semele managed to remain safe. It was at this time that Dionysus was thought to have fully returned to his godly state.

The Greeks worshipped Dionysus with two festivals known as Dionysia. The lesser Dionysia was held in December, and the greater was held in March. These Dionysia were usually marked by drunken orgies. The highlight of the festivities was the sparagmos. During this part of the ceremony, a live goat would be disemboweled, and the partygoers would feast upon its raw flesh. In Rome, Dionysus was known as Bacchus, and his festival, or Bacchanalia, was also extremely immoral, even by Rome’s standards. So immoral in fact, that the Roman Senate in 186 B.C., made a law forbidding the celebration of the Bacchanalia.