Cinema was first introduced to Japan in 1896 when the Kinetoscope, invented by Thomas Edison three years earlier, was imported to Kobe. The first public showing of a film was held on 25 November. This was soon followed by showings in Osaka, Tokyo and the rest of Japan. In February 1897, the Cinematographe, invented by the Lumiere brothers, was imported to Kobe.

Due to technical difficulties concerning the installation of electrical equipment, the first showing could not be held until February 15 when it was shown in Osaka. However, on the 16th the theater was full of people eager to see the new invention.

During the first two decades after cinema was introduced to Japan, it was considered to be an object of curiosity and was billed as a rare Western invention. Although each film was only two or three minutes long, the show began with an introduction of the new invention and the film to be projected, and the live musical accompaniment made for an exciting event.

It was rare that films were shown for more than a week at a time in any one hall. Afterward, they would be shown at locations in the surrounding countryside areas. As a result of this limited run, it was not practical to establish any permanent cinemas solely for the purpose of showing films.

One of the first Japanese companies that became involved in cinema was Yoshizawa. As early as the year 1902 it imported enough films from the West to allow for up to two months of showings at one location. This helped pave the way for the opening of Japan’s first permanent cinema in October 1903. The Denkikan, an X-ray clinic in the Tokyo entertainment quarter of Asakusa, was equipped with projection facilities.

This was followed by the opening of other cinemas nearby and Asakusa soon became the film center of Japan. In 1917 there was a total of 64 cinemas in Japan, with 21 in Asakusa. High prices were charged to see such films, and the middle and upper classes were targeted for advertisement. Also, most of the big film companies of the time created short films for businesses, in turn being solely financed by them. The businesses created every aspect of the films from script writing to directing, but left the production company with hearty payments.

Although cinema was introduced to Japan as early as 1896, there was very little activity in the area of film production for many years. Rather, much effort was made to design ways to show the imported Western films and to make the two or three-minute film sequences into popular attractions. Thus, each showing began with a narrator who explained the functions and operating principles of the projector.

Then he or she explained what the film to be shown was about. During the actual showing, this narrator commented on the film’s contents. In these early days of cinema in Japan, the only stars were indeed the narrators. As they were the ones who were in direct contact with the audience, they had a tremendous amount of power through their interpretation of the films that they accompanied.

Furthermore, it was not until almost the year 1920 when intertitles first appeared in Japanese films. Thus, it was truly the narrator who interpreted the film images and brought the characters to life for the audience.

Somei Saburo is recognized as the benshi who did the most to raise his performance to a high artistic level. Originally an actor, Somei worked with expositions and performances in Asakusa in 1896. He was hired by the Denkikan to be its first narrator.

Unlike other narrators of his time, Somei did not simply narrate his films and describe the contents thereof. He became his characters, giving each of them a voice and a distinct personality.

Thus, rather than remaining an outside observer of the film, he was the first narrator to enter the film and become a part of it. In this sense, he was the first benshi. Somei worked at the Denkikan for a number of years before switching to the Tekikokukan where he was one of the three main benshi.

With more and more innovations affecting Japanese cinema, it underwent a period of dramatic expansion. As cinema became an established art form, the popularity of the benshi rose and the influence that they had in the film making process grew in turn. The popularity of the benshi was such that theaters competed to hire the most talented and popular, and films were publicized more for the benshi that performed them, than for the actors who starred in them.

The name of the benshi was posted both outside the cinema and on the stage during his or her performance, during the early years of film production in Japan, there were several methods of film exhibition. Both the kinetescope and the cinematographe could project the images onto a screen, and the people wanted to see them.

Some of the early theatres would charge high prices to fill up the seats. There were usually two showings a day, and each would last from two to three hours, even though the film footage itself was only 20 minutes long. In the beginning, it took several people to run and switch the projectors, resulting in long pauses between reels.

As short films were replaced by feature length ones, the physical stress of recreating all the characters of a film became a difficult task for one benshi working alone. Theaters employed several benshi, who took turns performing a film. Each cinema had a premiere benshi who appeared to perform the climax of a film.

Although there is no exact record of the number of benshi working at any one time, records indicate that there were at least several thousand benshi active in Japan. In order to maintain standards of professional excellence, a benshi license, obtained upon passing an examination given by prefectural police, was required for all benshi.

In addition to the great influence that benshi had at the performance level, many famous benshi had strong input at the film making level. At cinemas managed by large film production and distribution companies, it was common for benshi to be shown film scripts before production began, and they often demanded a rewrite if they disagreed with any part.

Thus, at this point in the development of cinema, it was the performance side that held greater influence than the production side. In order to maintain his or her position among the great competition, each benshi developed an individual style.

The Jazz Singer, the first talkie, was shown in New York in 1927. This marked the beginning of the end of the silent film era. In the West, the transition took place rapidly, with the production of silent films ceasing almost instantly. In Japan however, due to technical difficulties involved with equipping theaters with sound-compatible facilities, silent films continued to be the norm for many years and were not entirely replaced by talkies until the year 1935.

Thus, the benshi polished their art and reigned in the world of Japanese cinema for almost two decades. Of course, the change from silent to sound did not take place without any resistance from the benshi. There were some minor strikes and demonstrations. But these were to no avail. Most benshi left the world of cinema for other endeavors. In the end, the art of the benshi, like so many other arts that have been lost with the ages, was allowed to fade away and virtually disappear in favor of something new and innovative.

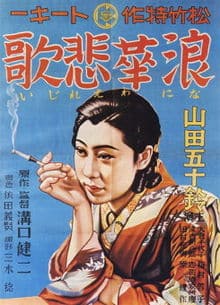

As technology continued to advance, more and more production companies came into power. Big directors and actors began to emerge to produce great feature-length films. The Osaka Elegy, directed by Kenji Mizoguchi, was one of his first great feature films.

The film centers around a young woman who worked as a telephonist for a pharmaceutical company, played by Isuzu Yamada. She allows herself to be set up as the mistress of her married boss, in order to resolve the debts of her drunken father and put her brother through school. Yamada is soon rejected by her boss and thrown out in the street. In desperation, she turns to prostitution and is rejected by her family.

The Elegy in the title explains the suffering of the character and others like her. This picture was made in 1936 and brought fame to Mizoguchi and began his creative partnership with the writer Yoshitaka Yoda, which would last for more than twenty films. The Osaka Elegy is a sharp scathing look at sexual politics in 1930’s Japan, it makes the audience think about the burden faced by Japanese women at the time, and is a film that will entertain and sadden all.

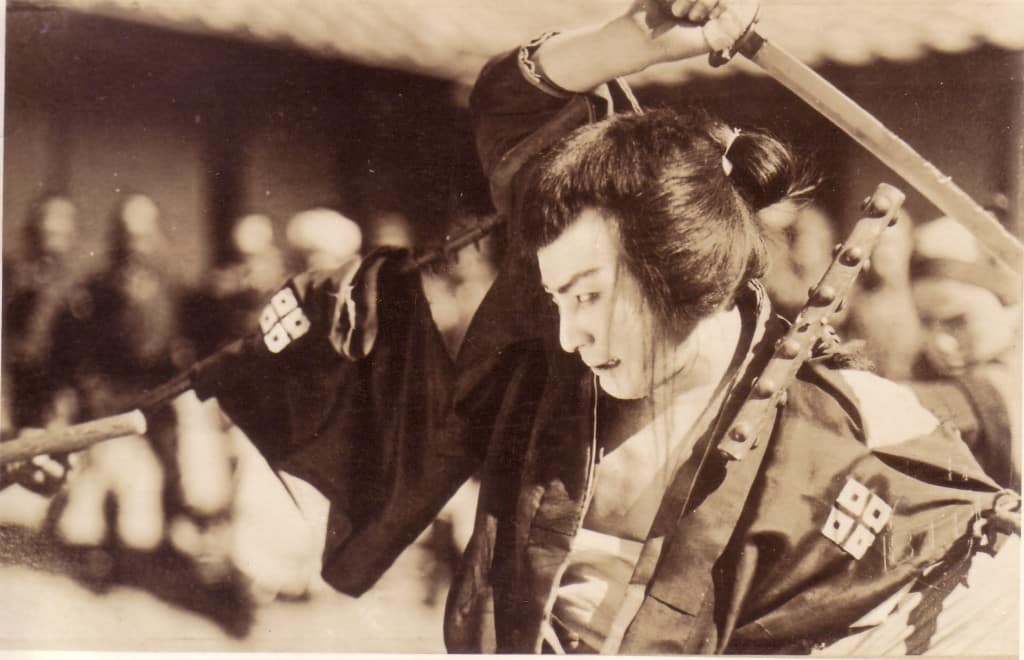

As the art of filmmaking grew, it began to incorporate many styles and genres of film. Film styles such as the gendai-geki, films about contemporary life, and the jidai-geki, the period-dramas, ruled the scene. These two styles were very popular among the Japanese audience, but soon to be released were the shomin-geki, films about the common people. These films included subjects from the proletarian and lower-middle classes, and were soon to become very popular themselves.

As with all forms of art in Japan, film and painting consisted of two schools, the Western-influenced and the purely Japanese. Japanese music, as well, is comprised of compositions made with Western influence as well as in the purely Japanese manner. The effect that Western societies had on the arts of Japan was extensive and had a major impact on the products.

The United States had Hollywood, and produced some of the most popular films of the times; this could be an affect of the Western influence. Japan wanted to participate in this highly competitive industry. As long as there are divided countries and divided ways of living, this Western influence is going to continue to affect all nations in the world.

Japan has made its mark within the film industry. It began just as all other forms of art have, with new inventions furthering and pushing the directors and producers of the times to constantly strive for bigger and better films. It was a difficult feat to make the transition from low budget, silent, short films to the technologically advanced films we see today.

The theaters, directors, actors, audience, and everyone involved in the process have watched the industry grow to the beautiful form of art we see today. This growth is crucial to the industry as with all forms of art, it must keep improving with the new innovations or the industry could collapse. With the film industry being as competitive as it is, Japan has managed to improve while staying unique.

While the United States continues to dominate the industry, Japan is able to keep its history and styles to produce unique films exclusive to Japan. The country has contributed immensely to the art of filmmaking and will continue to do so for as long as this form of entertainment is popular.