Civil Rights Movement in the United States, political, legal, and social struggle by black Americans to gain full citizenship rights and to achieve racial equality. The civil rights movement was first and foremost a challenge to segregation, the system of laws and customs separating blacks and whites that whites used to control blacks after slavery was abolished in the 1860s.

During the civil rights movement, individuals and civil rights organizations challenged segregation and discrimination with a variety of activities, including protest marches, boycotts, and refusal to abide by segregation laws. Many believe that the movement began with the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 and ended with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, though there is debate about when it began and whether it has ended yet.

The civil rights movement has also been called the Black Freedom Movement, the Negro Revolution, and the Second Reconstruction.

Segregation

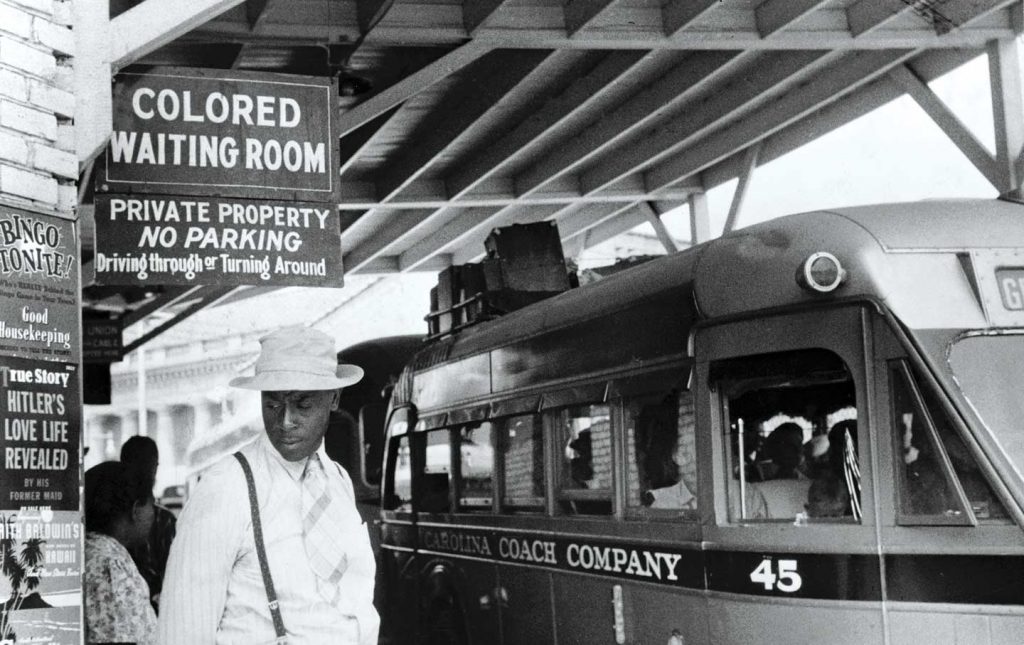

Segregation was an attempt by white Southerners to separate the races in every sphere of life and to achieve supremacy over blacks. Segregation was often called the Jim Crow system, after a minstrel show character from the 1830s who was an old, crippled, black slave who embodied negative stereotypes of blacks. Segregation became common in Southern states following the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

During Reconstruction, which followed the Civil War (1861-1865), Republican governments in the Southern states were run by blacks, Northerners, and some sympathetic Southerners. The Reconstruction governments had passed laws opening up economic and political opportunities for blacks. By 1877 the Democratic Party had gained control of the government in the Southern states, and these Southern Democrats wanted to reverse black advances made during Reconstruction.

To that end, they began to pass local and state laws that specified certain places “For Whites Only” and others for “Colored.” Blacks had separate schools, transportation, restaurants, and parks, many of which were poorly funded and inferior to those of whites. Over the next 75 years, Jim Crow signs went up to separate the races in every possible place.

The system of segregation also included the denial of voting rights, known as disfranchisement. Between 1890 and 1910 all Southern states passed laws imposing requirements for voting that were used to prevent blacks from voting, in spite of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which had been designed to protect black voting rights.

These requirements included: the ability to read and write, which disqualified the many blacks who had not had access to education; property ownership, something few blacks were able to acquire; and paying a poll tax, which was too great a burden on most Southern blacks, who were very poor. As a final insult, the few blacks who made it over all these hurdles could not vote in the Democratic primaries that chose the candidates because they were open only to whites in most Southern states.

Because blacks could not vote, they were virtually powerless to prevent whites from segregating all aspects of Southern life. They could do little to stop discrimination in public accommodations, education, economic opportunities, or housing.

The ability to struggle for equality was even undermined by the prevalent Jim Crow signs, which constantly reminded blacks of their inferior status in Southern society. Segregation was an all-encompassing system.

Conditions for blacks in Northern states were somewhat better, though up to 1910 only about 10 percent of blacks lived in the North, and prior to World War II (1939-1945), very few blacks lived in the West. Blacks were usually free to vote in the North, but there were so few blacks that their voices were barely heard. Segregated facilities were not as common in the North, but blacks were usually denied entrance to the best hotels and restaurants.

Schools in New England were usually integrated, but those in the Midwest generally were not. Perhaps the most difficult part of Northern life was the intense economic discrimination against blacks. They had to compete with large numbers of recent European immigrants for job opportunities and almost always lost.

Early Black Resistance to Segregation

Blacks fought against discrimination whenever possible. In the late 1800s blacks sued in court to stop separate seating in railroad cars, states’ disfranchisement of voters, and denial of access to schools and restaurants.

One of the cases against segregated rail travel was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that “separate but equal” accommodations were constitutional. In fact, separate was almost never equal, but the Plessy doctrine provided constitutional protection for segregation for the next 50 years.

To protest segregation, blacks created new national organizations. The National Afro-American League was formed in 1890; the Niagara Movement in 1905; and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. In 1910 the National Urban League was created to help blacks make the transition to urban, industrial life.

The NAACP became one of the most important black protest organizations of the 20th century. It relied mainly on a legal strategy that challenged segregation and discrimination in courts to obtain equal treatment for blacks. An early leader of the NAACP was the historian and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, who starting in 1910 made powerful arguments in favor of protesting segregation as editor of the NAACP magazine, The Crisis.

NAACP lawyers won court victories over voter disfranchisement in 1915 and residential segregation in 1917, but failed to have lynching outlawed by the Congress of the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. These cases laid the foundation for a legal and social challenge to segregation although they did little to change everyday life.

In 1935 Charles H. Houston, the NAACP’s chief legal counsel, won the first Supreme Court case argued by exclusively black counsel representing the NAACP. This win invigorated the NAACP’s legal efforts against segregation, mainly by convincing courts that segregated facilities, especially schools, were not equal. In 1939 the NAACP created a separate organization called the NAACP Legal Defense Fund that had a nonprofit, tax-exempt status that was denied to the NAACP because it lobbied the U.S. Congress.

Houston’s chief aide and later his successor, Thurgood Marshall, a brilliant young lawyer who would become a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, began to challenge segregation as a lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

World War I

When World War I (1914-1918) began, blacks enlisted to fight for their country. However, black soldiers were segregated, denied the opportunity to be leaders, and were subjected to racism within the armed forces. During the war, hundreds of thousands of Southern blacks migrated northward in 1916 and 1917 to take advantage of job openings in Northern cities created by the war.

This great migration of Southern blacks continued into the 1950s. Along with the great migration, blacks in both the North and South became increasingly urbanized during the 20th century. In 1890, about 85 percent of all Southern blacks lived in rural areas; by 1960 that percentage had decreased to about 42 percent. In the North, about 95 percent of all blacks lived in urban areas in 1960.

The combination of the great migration and the urbanization of blacks resulted in black communities in the North that had a strong political presence. The black communities began to exert pressure on politicians, voting for those who supported civil rights. These Northern black communities, and the politicians that they elected, helped Southern blacks struggling against segregation by using political influence and money.

The 1930s

The Great Depression of the 1930s increased black protests against discrimination, especially in Northern cities. Blacks protested the refusal of white-owned businesses in all-black neighborhoods to hire black salespersons. Using the slogan “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work,” these campaigns persuaded blacks to boycott those businesses and revealed a new militancy. During the same years, blacks organized school boycotts in Northern cities to protest the discriminatory treatment of black children.

The black protest activities of the 1930s were encouraged by the expanding role of government in the economy and society. During the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the federal government created federal programs, such as Social Security, to assure the welfare of individual citizens.

Roosevelt himself was not an outspoken supporter of black rights, but his wife Eleanor became an open advocate for fairness to blacks, as did other leaders in the administration. The Roosevelt Administration opened federal jobs to blacks and turned the federal judiciary away from its preoccupation with protecting the freedom of business corporations and toward the protection of individual rights, especially those of the poor and minority groups.

Beginning with his appointment of Hugo Black to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1937, Roosevelt chose judges who favored black rights. As early as 1938, the courts displayed a new attitude toward black rights; that year the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Missouri was obligated to provide access to a public law school for blacks just as it provided for whites. A new emphasis on the equal part of the Plessy doctrine. Blacks sensed that the national government might again be their ally, as it had been during the Civil War.

World War II

When World War II began in Europe in 1939, blacks demanded better treatment than they had experienced in World War I. Black newspaper editors insisted during 1939 and 1940 that black support for this war effort would depend on fair treatment. They demanded that black soldiers be trained in all military roles and that black civilians have equal opportunities to work in war industries at home.

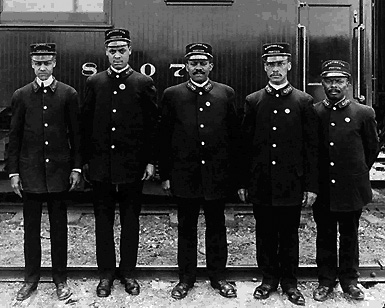

In 1941 A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a union whose members were mainly black railroad workers, planned a March on Washington to demand that the federal government require defense contractors to hire blacks on an equal basis with whites.

To forestall the march, President Roosevelt issued an executive order to that effect and created the federal Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to enforce it. The FEPC did not prevent discrimination in war industries, but it did provide a lesson to blacks about how the threat of protest could result in new federal commitments to civil rights.

During World War II, blacks composed about one-eighth of the U.S. armed forces, which matched their presence in the general population. Although a disproportionately high number of blacks were put in non-combat, support positions in the military, many did fight. The Army Air Corps trained blacks as pilots in a controversial segregated arrangement in Tuskegee, Alabama. During the war, all the armed services moved toward equal treatment of blacks, though none flatly rejected segregation.

In the early war years, hundreds of thousands of blacks left Southern farms for war jobs in Northern and Western cities. In fact, more blacks migrated to the North and the West during World War II than had left during the previous war. Although there were racial tension and conflict in their new homes, blacks were free of the worst racial oppression, and they enjoyed much larger incomes. After the war blacks in the North and West used their economic and political influence to support civil rights for Southern blacks.

Blacks continued to work against discrimination during the war, challenging voting registrars in Southern courthouses and suing school boards for equal educational provisions. The membership of the NAACP grew from 50,000 to about 500,000. In 1944 the NAACP won a major victory in Smith v. Allwright, which outlawed the white primary. A new organization, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), was founded in 1942 to challenge segregation in public accommodations in the North.

During the war, black newspapers campaigned for a Double V, victories over both fascism in Europe and racism at home. The war experience gave about one million blacks the opportunity to fight racism in Europe and Asia, a fact that black veterans would remember during the struggle against racism at home after the war. Perhaps just as important, almost ten times that many white Americans witnessed the patriotic service of black Americans. Many of them would object to the continued denial of civil rights to the men and women beside whom they had fought.

After World War II the momentum for racial change continued. Black soldiers returned home with determination to have full civil rights. President Harry Truman ordered the final desegregation of the armed forces in 1948. He also committed to a domestic civil rights policy favoring voting rights and equal employment, but the U.S. Congress rejected his proposals.

School Desegregation

In the postwar years, the NAACP’s legal strategy for civil rights continued to succeed. Led by Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund challenged and overturned many forms of discrimination, but their main thrust was equal educational opportunities. For example, in Sweat v. Painter (1950), the Supreme Court decided that the University of Texas had to integrate its law school. Marshall and the Defense Fund worked with Southern plaintiffs to challenge the Plessy doctrine directly, arguing in effect that separate was inherently unequal. The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on five cases that challenged elementary- and secondary-school segregation, and in May 1954 issued its landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that stated that racially segregated education was unconstitutional.

White Southerners received the Brown decision first with shock and, in some instances, with expressions of goodwill. By 1955, however, white opposition in the South had grown into massive resistance, a strategy to persuade all whites to resist compliance with the desegregation orders. It was believed that if enough people refused to cooperate with the federal court order, it could not be enforced.

Tactics included firing school employees who showed a willingness to seek integration, closing public schools rather than desegregating, and boycotting all public education that was integrated. The White Citizens Council was formed and led the opposition to school desegregation all over the South. The Citizens Council called for economic coercion of blacks who favored integrated schools, such as firing them from jobs, and the creation of private, all-white schools.

Virtually no schools in the South were desegregated in the first years after the Brown decision. In Virginia, one county did indeed close its public schools. In Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, Governor Orval Faubus defied a federal court order to admit nine black students to Central High School, and President Dwight Eisenhower sent federal troops to enforce desegregation.

The event was covered by the national media, and the fate of the Little Rock Nine, the students attempting to integrate the school, dramatized the seriousness of the school desegregation issue to many Americans. Although not all school desegregation was as dramatic as in Little Rock, the desegregation process did proceed-gradually. Frequently schools were desegregated only in theory because racially segregated neighborhoods led to segregated schools. To overcome this problem, some school districts in the 1970s tried busing students to schools outside of their neighborhoods.

As desegregation progressed, the membership of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) grew. The KKK used violence or threats against anyone who was suspected of favoring desegregation or black civil rights. Klan terror, including intimidation and murder, was widespread in the South in the 1950s and 1960s, though Klan activities were not always reported in the media. One terrorist act that did receive national attention was the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy slain in Mississippi by whites who believed he had flirted with a white woman. The trial and acquittal of the men accused of Till’s murder were covered in the national media, demonstrating the continuing racial bigotry of Southern whites.

Political Protest

Montgomery Bus Boycott: Despite the threats and violence, the struggle quickly moved beyond school desegregation to challenge segregation in other areas. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a member of the Montgomery, Alabama, branch of the NAACP, was told to give up her seat on a city bus to a white person. When Parks refused to move, she was arrested. The local NAACP, led by Edgar D. Nixon, recognized that the arrest of Parks might rally local blacks to protest segregated buses.

Montgomery’s black community had long been angry about their mistreatment on city buses where white drivers were often rude and abusive. The community had previously considered a boycott of the buses, and almost overnight one was organized.

The Montgomery bus boycott was an immediate success, with virtually unanimous support from the 50,000 blacks in Montgomery. It lasted for more than a year and dramatized to the American public the determination of blacks in the South to end segregation. A federal court ordered Montgomery’s buses desegregated in November 1956, and the boycott ended in triumph.

A young Baptist minister named Martin Luther King, Jr., was president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization that directed the boycott. The protest made King a national figure. His eloquent appeals to Christian brotherhood and American idealism created a positive impression on people both inside and outside the South. King became the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) when it was founded in 1957.

SCLC wanted to complement the NAACP legal strategy by encouraging the use of nonviolent, direct action to protest segregation. These activities included marches, demonstrations, and boycotts. The violent white response to black direct action eventually forced the federal government to confront the issues of injustice and racism in the South.

In addition to his large following among blacks, King had a powerful appeal to liberal Northerners that helped him influence national public opinion. His advocacy of nonviolence attracted supporters among peace activists. He forged alliances in the American Jewish community and developed strong ties to the ministers of wealthy, influential Protestant congregations in Northern cities. King often preached to those congregations, where he raised funds for SCLC.

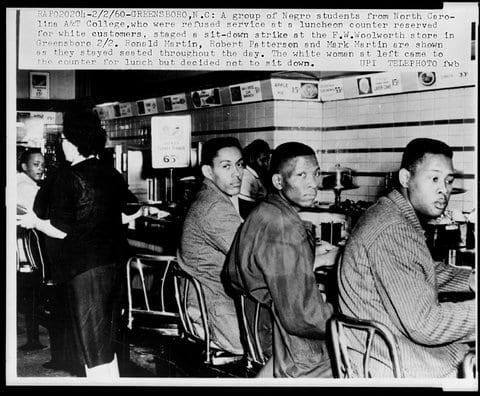

The Sit-Ins

On February 1, 1960, four black college students at North Carolina A&T University began protesting racial segregation in restaurants by sitting at “white-only” lunch counters and waiting to be served. This was not a new form of protest, but the response to the sit-ins in North Carolina was unique.

Within days sit-ins had spread throughout North Carolina, and within weeks they were taking place in cities across the South. Many restaurants were desegregated. The sit-in movement also demonstrated clearly to blacks and whites alike that young blacks were determined to reject segregation openly.

In April 1960 the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded in Raleigh, North Carolina, to help organize and direct the student sit-in movement. King encouraged SNCC’s creation, but the most important early advisor to the students was Ella Baker, who had worked for both the NAACP and SCLC. She believed that SNCC should not be part of SCLC but a separate, independent organization run by the students.

She also believed that civil rights activities should be based in individual black communities. SNCC adopted Baker’s approach and focused on making changes in local communities, rather than striving for national change. This goal differed from that of SCLC which worked to change national laws. During the civil rights movement, tensions occasionally arose between SCLC and SNCC because of their different methods.

Freedom Riders

After the sit-ins, some SNCC members participated in the 1961 Freedom Rides organized by CORE. The Freedom Riders, both black and white, traveled around the South in buses to test the effectiveness of a 1960 Supreme Court decision. This decision had declared that segregation was illegal in bus stations that were open to interstate travel.

The Freedom Rides began in Washington, D.C. Except for some violence in Rock Hill, South Carolina, the trip southward was peaceful until they reached Alabama, where violence erupted. At Anniston, one bus was burned and some riders were beaten. In Birmingham, a mob attacked the riders when they got off the bus. They suffered even more severe beatings by a mob in Montgomery, Alabama.

The violence brought national attention to the Freedom Riders and fierce condemnation of Alabama officials for allowing the violence. The administration of President John Kennedy interceded to protect the Freedom Riders when it became clear that Alabama state officials would not guarantee safe travel. The riders continued on to Jackson, Mississippi, where they were arrested and imprisoned at the state penitentiary, ending the protest.

The Freedom Rides did result in the desegregation of some bus stations, but more importantly, they demonstrated to the American public how far civil rights workers would go to achieve their goals.

SCLC Campaigns

SCLC’s greatest contribution to the civil rights movement was a series of highly publicized protest campaigns in Southern cities during the early 1960s. These protests were intended to create such public disorder that local white officials and business leaders would end segregation in order to restore normal business activity.

The demonstrations required the mobilization of hundreds, even thousands, of protesters who were willing to participate in protest marches as long as necessary to achieve their goal and who were also willing to be arrested and sent to jail.

The first SCLC direct-action campaign began in 1961 in Albany, Georgia, where the organization joined local demonstrations against segregated public accommodations.

The presence of SCLC and King escalated the Albany protests by bringing national attention and additional people to the demonstrations, but the demonstrations did not force negotiations to end segregation. During months of protest, Albany’s police chief continued to jail demonstrators without a show of police violence. The Albany protests ended in failure.

In the spring of 1963, however, the direct-action strategy worked in Birmingham, Alabama. SCLC joined the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, a local civil rights leader, who believed that the Birmingham police commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor, would meet protesters with violence. In May the SCLC staff stepped up antisegregation marches by persuading teenagers and school children to join.

The singing and chanting adolescents who filled the streets of Birmingham caused Connor to abandon restraint. He ordered police to attack demonstrators with dogs and firefighters to turn high-pressure water hoses on them. The ensuing scenes of violence were shown throughout the nation and the world in newspapers, magazines, and most importantly, on television.

Much of the world was shocked by the events in Birmingham, and the reaction to the violence increased support for black civil rights. In Birmingham white leaders promised to negotiate an end to some segregation practices. Business leaders agreed to hire and promote more black employees and to desegregate some public accommodations. More important, however, the Birmingham demonstrations built support for national legislation against segregation.

Desegregating Southern Universities

In 1962 a black man from Mississippi, James Meredith, applied for admission to University of Mississippi. His action was an example of how the struggle for civil rights belonged to individuals acting alone as well as to organizations. The university attempted to block Meredith’s admission, and he filed suit. After working through the state courts, Meredith was successful when a federal court ordered the university to desegregate and accept Meredith as a student.

The governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, defied the court order and tried to prevent Meredith from enrolling. In response, the administration of President Kennedy intervened to uphold the court order. Kennedy sent federal marshals with Meredith when he attempted to enroll. During his first night on campus, a riot broke out when whites began to harass the federal marshals. In the end, 2 people were killed, and about 375 people were wounded.

When the governor of Alabama, George C. Wallace, threatened a similar stand, trying to block the desegregation of the University of Alabama in 1963, the Kennedy Administration responded with the full power of the federal government, including the U.S. Army, to prevent violence and enforce desegregation. The showdowns with Barnett and Wallace pushed Kennedy, whose support for civil rights up to that time had been tentative, into a full commitment to end segregation.

The March on Washington

The national civil rights leadership decided to keep pressure on both the Kennedy administration and the Congress to pass civil rights legislation by planning a March on Washington for August 1963. It was a conscious revival of A. Philip Randolph’s planned 1941 march, which had yielded a commitment to fair employment during World War II.

Randolph was there in 1963, along with the leaders of the NAACP, CORE, SCLC, the Urban League, and SNCC. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered the keynote address to an audience of more than 200,000 civil rights supporters. His “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the giant sculpture of the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, became famous for how it expressed the ideals of the civil rights movement.

Partly as a result of the March on Washington, President Kennedy proposed a new civil rights law. After Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, the new president, Lyndon Johnson, strongly urged its passage as a tribute to Kennedy’s memory.

Over fierce opposition from Southern legislators, Johnson pushed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 through Congress. It prohibited segregation in public accommodations and discrimination in education and employment. It also gave the executive branch of government the power to enforce the act’s provisions.

Voter Registration

The year 1964 was the culmination of SNCC’s commitment to civil rights activism at the community level. Starting in 1961 SNCC and CORE organized voter registration campaigns in heavily black, rural counties of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. SNCC concentrated on voter registration, believing that voting was a way to empower blacks so that they could change racist policies in the South. SNCC worked to register blacks to vote by teaching them the necessary skills-such as reading and writing-and the correct answers to the voter registration application.

SNCC worker Robert Moses led a voter registration effort in McComb, Mississippi, in 1961, and in 1962 and 1963 SNCC worked to register voters in the Mississippi Delta, where it found local supporters like the farm-worker and activist Fannie Lou Hamer. These civil rights activities caused violent reactions from Mississippi’s white supremacists. Moses faced constant terrorism that included threats, arrests, and beatings. In June 1963 Medgar Evers, NAACP field secretary in Mississippi, was shot and killed in front of his home.

In 1964 SNCC workers organized the Mississippi Summer Project to register blacks to vote in that state. SNCC leaders also hoped to focus national attention on Mississippi’s racism. They recruited Northern college students, teachers, artists, and clergy-both black and white-to work on the project, because they believed that the participation of these people would make the country more concerned about discrimination and violence in Mississippi.

The project did receive national attention, especially after three participants, two of whom were white, disappeared in June and were later found murdered and buried near Philadelphia, Mississippi. By the end of the summer, the project had helped thousands of blacks attempt to register, and about 1000 had actually become registered voters.

The Summer Project increased the number of blacks who were politically active and led to the creation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). When white Democrats in Mississippi refused to accept black members in their delegation to the Democratic National Convention of 1964, Hamer and others went to the convention to challenge the white Democrats’ right to represent Mississippi.

In a televised interview, Hamer detailed the harassment and abuse experienced by black Mississippians when they tried to register to vote. Her testimony attracted much media attention, and President Johnson was upset by the disturbance at the convention where he expected to be nominated for president.

National Democratic Party officials offered the black Mississippians two convention seats, but the MFDP rejected the compromise offer and went home. Later, however, the MFDP challenge did result in more support for blacks and other minorities in the Democratic Party.

In early 1965 SCLC employed its direct-action techniques in a voting-rights protest initiated by SNCC in Selma, Alabama. When protests at the local courthouse were unsuccessful, protesters began a march to Montgomery, the state capital.