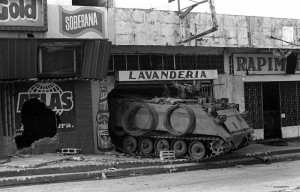

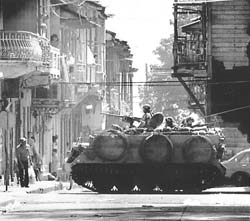

The U.S. invasion of Panama on December 20, 1989 was a mark of excellence on the behalf of the U.S. armed forces ability to effectively use the principles of war. The years leading up to the invasion set the climate for conflict; drug trafficking became a major problem between Panama and the U.S. in the 1980’s, as well as Manuel Noriega’s interference with the Panama canal employees rights under the Panama Canal Treaty; the final action that sparked the invasion was Noriega’s attempt to fix the national election and the military enforcement of the fix after the election. Once this took place the U.S. began to make a plan for the invasion. The overwhelming success of this mission stemmed from the U.S. military’s competent use of the principals of war.

The primary success of a mission is the ability to define an overall attainable objective for the mission. In the formulation of the mission to  invade Panama, the U.S. military set out four main objectives of the mission. First, they wanted to “protect American lives” (Watson 69). This meant they wanted to protect the lives of the 35,000 U.S. citizens in Panama from attacks by Noriega’s Panama Defense Force or PDF; they also wanted to protect the lives of Americans at home by attempting to eliminate drug trafficking. Second, they wanted to “protect American interests and rights under the Panama Canal Treaty” (Watson 69). This could be done by abolishing Noriega’s control of the workers who operate the canal, and his control of the canal itself. Third, they wanted to “restore a democratic and freely elected government to Panama” (Watson 107). Here, the U.S. would gain control over the country and ensure a fair election. And, finally, they wanted to “apprehend Noriega” (Watson 69) for prosecution in the U.S.. This would ease the difficulty of restoring democracy and eliminating drug trafficking, as well as giving Americans a feeling that justice was being served. These objectives gave the mission clear goals to achieve, allowing for the planing of each task that needed to be completed in order to accomplish the mission.

invade Panama, the U.S. military set out four main objectives of the mission. First, they wanted to “protect American lives” (Watson 69). This meant they wanted to protect the lives of the 35,000 U.S. citizens in Panama from attacks by Noriega’s Panama Defense Force or PDF; they also wanted to protect the lives of Americans at home by attempting to eliminate drug trafficking. Second, they wanted to “protect American interests and rights under the Panama Canal Treaty” (Watson 69). This could be done by abolishing Noriega’s control of the workers who operate the canal, and his control of the canal itself. Third, they wanted to “restore a democratic and freely elected government to Panama” (Watson 107). Here, the U.S. would gain control over the country and ensure a fair election. And, finally, they wanted to “apprehend Noriega” (Watson 69) for prosecution in the U.S.. This would ease the difficulty of restoring democracy and eliminating drug trafficking, as well as giving Americans a feeling that justice was being served. These objectives gave the mission clear goals to achieve, allowing for the planing of each task that needed to be completed in order to accomplish the mission.

Once objective has been established, the next step was to derive a simple plan, following the principle of simplicity, which is the formation of “Direct, simple plans and clear, concise orders to minimize misunderstanding and confusion” (Stofft 7). That is just what the U.S. did. They used direct and simple plans to carry out their mission; that is not to say the invasion was a simple operation, on the contrary, the command and control measures were very difficult. Thus, the plan was as simple as it could be with concern to the difficulty of the operation.

The next principal of war is the concept of taking the offensive, this gives the commander the ability to “impose his will upon the enemy” (Stofft 6). Thus the commander keeps his enemy on the run, reacting instead of acting. This is a principal the U.S. military did well; they attacked with speed, accomplishing mission after mission until their objectives had been reached. The U.S. did not allow the PDF to retaliate; according to Watson the purpose of the U.S. offensive was to “defeat the PDF so decisively that those loyal to Noriega would be thoroughly demoralized and unable to organize a guerrilla campaign…” (Watson 70). From the initial attack to the capture of Noriega only spanned 12 days, leaving no time for an effective counter-attack. In this, the U.S. obeyed the principal of offensive, which helped lead to victory.

In order to maintain an effective offensive there must be effective unity of command. This principal of war is vital to any mission. Unity of  command “obtains unity of effort by the coordinated action of all forces toward a common goal…it is best achieved by vesting a single commander with the requisite authority” (Stofft 7). From the beginning, the U.S. heeded this principle of war. Flanagan points out that General Thurman “insisted on its application in this operation” (Flanagan 34). He also states that, “General Stiner would be in overall command of all U.S. combat forces, regardless of service, including Special Operations Forces” (Flanagan 34). In this a strong chain of command was formed, everyone knew who was in charge. Thus, there was no room left open for conflicting orders from two different commanders.

command “obtains unity of effort by the coordinated action of all forces toward a common goal…it is best achieved by vesting a single commander with the requisite authority” (Stofft 7). From the beginning, the U.S. heeded this principle of war. Flanagan points out that General Thurman “insisted on its application in this operation” (Flanagan 34). He also states that, “General Stiner would be in overall command of all U.S. combat forces, regardless of service, including Special Operations Forces” (Flanagan 34). In this a strong chain of command was formed, everyone knew who was in charge. Thus, there was no room left open for conflicting orders from two different commanders.

The next principle of war is the concept of mass, which states, “Superior combat power must be concentrated at the critical time and place for a decisive purpose” (Stofft 6). The U.S. military effectively used this principal during the invasion, using “over 26,000 U.S. personnel from all services” (Watson 107). The U.S. massed its troops by using approximately 13,000 “in country” troops, as well as 9,500 troops flown in during the operation (Watson 71). These troops were mass in the country just prior to H-hour in order to suppress approximately 19,600 PDF soldiers and 12,300 Dignity Battalion personnel (Watson 70). The numbers seem to be in favor of the Panamanian military, but the U.S. made up for this with the effective use of its troops.

This use is known as economy of force, which says, “Skillful and prudent use of combat power will enable the commander to accomplish the mission with minimum expenditure of resources” (Stofft 6). The U.S. military also effectively used this principal during the invasion; for the invasion the U.S. split its force into five main task forces, each assigned to perform a specific task within the mission. For example, task force Semper Fi was assigned to “block the western approaches to the city and secure the Bridge of the Americas” (Watson 44). By using the task forces to attack specific logistical areas with the minimum force necessary, the U.S. was able to over-run and scare the PDF into hiding by making it seem like there was a larger than was actually present; by this the U.S. was able to minimize losses and maximize results.

The principle of war the U.S. did not perform as well as they could have is the principle of Security. Security is accomplished by “measures taken to prevent surprise, preserve freedom of action, and deny the enemy of information of friendly forces” (Stofft 6). On the night the  invasion was to take place, information about H-hour was compromised by the enemy about three hours prior to the invasion. The result of this compromise was “warnings on Panamanian radio that the U.S. was attacking at 1 a.m. and that PDF units should report, draw arms, and prepare to fight” (Watson 83). The U.S. had lost the principle of surprise, which is achieved by “striking an enemy at a time, place, and in a manner for which he is not prepared” (Stofft 7). Without security the enemy would be ready when H-hour did arrive. The U.S. did attempt to maintain the element of surprise by using the principle of maneuver, an action performed to put the Panamanian military at a “relative disadvantage” (Stofft 7). To do so they moved the time for H-hour up by 15 minutes in hopes to confuse the enemy.

invasion was to take place, information about H-hour was compromised by the enemy about three hours prior to the invasion. The result of this compromise was “warnings on Panamanian radio that the U.S. was attacking at 1 a.m. and that PDF units should report, draw arms, and prepare to fight” (Watson 83). The U.S. had lost the principle of surprise, which is achieved by “striking an enemy at a time, place, and in a manner for which he is not prepared” (Stofft 7). Without security the enemy would be ready when H-hour did arrive. The U.S. did attempt to maintain the element of surprise by using the principle of maneuver, an action performed to put the Panamanian military at a “relative disadvantage” (Stofft 7). To do so they moved the time for H-hour up by 15 minutes in hopes to confuse the enemy.

In the final outcome of the invasion it is obvious that the U.S. military’s mastery of the principles of war were the decisive factor in the completion of their mission in Panama.

By using the principles of war the U.S. military minimized the loss of American lives, while maximizing their results, demonstrating the overall effectiveness of the principles of war.

Bibliography

1. Flanagan, Edward M., Jr.. Battle for Panama: Inside Operation Just cause. Brassey’s, Inc., Washington, 1993.

2. Stofft, William A.. American Military History. Army Historical Series. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1988.

3. Watson, Bruce. Operation Just Cause: The U.S. Intervention in Panama. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1991.