John Muir was a man of great importance in the history of the United States and in the preservation of it’s beauty. His tireless efforts to protect natural wonders such as Yosemite Valley demonstrated his undying love for the outdoors.

Muir took a stand against the destructive side of civilization in a dauntless battle to save America’s forest lands. The trail of preservation that Muir left behind has given countless numbers of people the opportunity to experience nature’s magnificence.

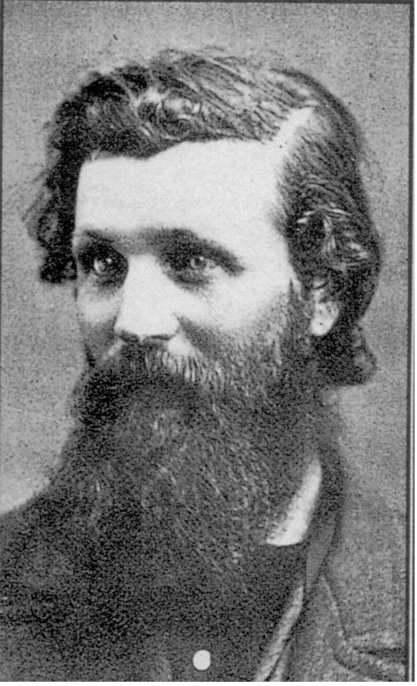

John Muir was born on April 21, 1838 in the small rural town of Dunbar, Scotland. As a boy, Muir was “fond of everything that was wild”(My Boyhood and Youth 30) and took great pleasure in the outdoors. In 1849, Muir and his family immigrated to Wisconsin to homestead.

The great forests of Northern United States captivated him and fueled his desire to learn more. Muir later enrolled in courses in chemistry, geology, and botany at the University of Wisconsin.

After his education, Muir began working in a factory inventing small machines and contraptions. However, a serious working accident in the factory left Muir temporarily blind. When he finally regained his vision, he vowed to live life to the fullest and devote everything he had to nature.

At the age of 29, Muir made a thousand-mile walk from Indianapolis to Florida for the sheer pleasure of being outdoors. This experience enlightened Muir and compelled him to extend his travels. With his family’s blessings (his wife and two daughters), he began to wander America’s forests, mountains, valleys, and meadows extensively.

Alone and on foot, he filled his notebooks with sketches and descriptions of the plants, animals, and trees that he loved. He later took trips around the world, including destinations such as Europe and South America.

There he explored the Amazon basin and noted many new plant species. In Alaska, he became the first white man to see Glacier Bay. He definitely made an impact in Alaska’s history: Mount Muir, Muir Glacier, Muir Point, and Muir Inlet all carry his name.

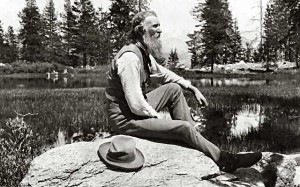

However, it was California’s Sierra Nevada and Yosemite Valley that truly claimed him. In 1868, he walked across the San Joaquin Valley through waist-high wildflowers and into the high country for the first time. Later he would write: “Then it seemed to me the Sierra should be called not the Nevada, or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light…the most divinely beautiful of all the mountain chains I have ever seen”(Wolfe, 230).

By 1871, Muir had found living glaciers in the Sierra and had conceived his controversial theory of the glaciation of Yosemite Valley. Muir’s reputation for exploration, glaciation, and environmental studies began to be well known throughout the country. Famous men of the time – Joseph LeConte, Asa Gray, and Ralph Waldo Emerson – made their way to the door of his pine cabin.

In later years he turned seriously to writing; publishing 300 articles and 10 major books composed of his travel journals. They recounted his travels, expounded his naturalist philosophy, and beckoned everyone to “climb the mountains and get their good tidings”(Muir, Life and Letters, 34). Muir’s love of the high country gave his writings a spiritual quality. His readers, whether they be presidents, congressmen, or plain folks, were inspired and often moved to action by the enthusiasm of Muir’s own unbounded love of nature.

Through a series of articles appearing in Century magazine, Muir drew attention to the devastation of mountain meadows and forests by sheep and cattle. With the help of Century’s associate editor, Robert Underwood Johnson, Muir worked to remedy this destruction. In 1890, due in large part to the efforts of Muir and Johnson, an act of Congress created Yosemite National Park. Muir was also personally involved in the creation of Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest, and Grand Canyon National Parks. Muir

deservedly is often called the “Father of Our National Park System.”

Johnson and others suggested to Muir that an association be formed to protect the newly created Yosemite National Park from the assaults of stockmen and others who would diminish its boundaries. In 1892, Muir and a number of his supporters founded the Sierra Club to, in Muir’s words, “do something for wildness and make the mountains glad”(Muir, Summer, 47). It was established specifically to rally citizens who believed in the preservation of the High Sierra and who understood the need for eternal vigilance in its protection. Muir served as the Club’s first president.

In 1901, Muir published Our National Parks. The book brought him national attention, influencing President Theodore Roosevelt. In May of 1903, Roosevelt and Muir traveled to Yosemite. Roosevelt was awestruck by the captivating scenery and beauty of the valley. For the duration of the three-day camping excursion, Muir preached the importance of preventing “the destructive work of the lumbermen and other spoilers of the for-est”(Wadsworth, 112). There, together, beneath the trees, they laid the foundation of Roosevelt’s innovative and notable conservation programs.

However, the trail of John Muir was not always a smooth one. He fought syndicates, congress, and lobbyists. “The battle we have fought, and are still fighting… is a part of the eternal conflict between right and wrong, and we cannot expect to see the end of it”(Browning 53).

The growing city of San Francisco was in need of a constantly expanding water supply. Hetch Hetchy Valley, north of Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park, was a prime location for a dam that would create a lake where the Tuolumne River was. Because it was completely within the National Park, there would be no private property to buy the land from. Muir was strongly opposed to the proposition right from the beginning. He argued that “This valley… is one of the sublime and beautiful and important features of the Park, and to dam and submerge it would be contradictive [to what] they were intended for when the Park was established”(Silverberg, 233).

To Muir’s dismay, he found the Sierra Club was divided: a strong minority of members, living in San Francisco, were ready to sacrifice Hetch Hetchy to the city’s needs. Muir and his Sierra Club associate William Colby then set up a new organization, the Society for the Preservation of National Parks. At first the new organization was a success and it seemed that Hetch Hetchy would be safe.

However, when Woodrow Wilson took office in 1913, the new Secretary of the Interior, a San Franciscan lobbyist of Hetch Hetchy, pushed a bill through congress that allowed the construction of the dam. Muir set forth a flood of appeals, letters, articles, and statements, but to no avail. Hetch Hetchy was lost. Muir later said: “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedral’s and churches, for no holier temple, has ever been consecrated by the heart of man”(Browning, 65-6).

During this unpleasant affair, Muir’s health had been failing dramatically and the defeat was a devastating blow to his already weakened condition. On December 24, 1914, Muir died at the age of 76 in Los Angeles. In acknowledgment of his achievements, California has greatly recognized Muir as an important man to honor in the state’s history.

The Muir Woods National Monument in Marin County, Calif., and The John Muir Trail extending from Yosemite Valley to the summit of Mt. Whitney were established. Mount Muir, Muir Gorge, Muir Grove, Muir Lake, Muir Mountain, Muir Pass, and Muir’s Peak were also named after him. 1976 the California Historical Society voted John Muir the greatest Californian in the state’s history. California’s governor proclaimed every April 21 John Muir Day in honor of his birthday.

John Muir was perhaps this country’s most famous and influential naturalist and conservationist. He taught the people of his time and ours the importance of experiencing and protecting our natural heritage. His words have heightened our perception of nature. His personal and determined involvement in the great conservation questions of his time was and remains an inspiration and stepping stone for today’s environmental activists.

Richard Hawley, an active environmentalist and executive director and co-founder of Greenspace, a local environmentalist group in Cambria, commented on the achievements of Muir. “John Muir was a dedicated man that had a vision… and a passion for natural beauty. He is a guiding light for a lot of people. The legacy of John Muir lives on through The John Muir Trail and Yosemite National Park.” Hawley went on further to say that “conservation is critical… and Muir set [the environmental movement] in motion.”

Many people today follow the path of John Muir’s conservation. His teachings of nature and life live on through his writings. He possessed the foresight to know that the forests needed to be protected. He knew that they wouldn’t have lasted forever. The Sierra Club that he founded has helped save millions of acres of forest lands, and other national monuments that otherwise would have been destroyed. He truly took a stand for nature, and in doing so, took a stand for mankind.

“The whole wilderness seems to be alive and familiar, full of humanity. The very stones seem talkative, sympathetic, brotherly. No wonder when we consider that we all have the same Father and Mother.”

-John Muir, April 1911