‘Journey of the Magi’ (written in 1927, published in 1931 in the collection Ariel) is at the crossroad of Eliot’s poetic career that relents to a new direction of penitential poetry quietly searching for spiritual peace by confirming his renewal of faith in Anglican Christianity.

Between the publication of Ash Wednesday and Ariel, a short illustrating series of poems that include the present one as a Christian poem, during the two years of the hiatus, Eliot underwent colossal spiritual upheaval, culminating in his baptism into the Church of England in June, 1927.

Despite its genre as a Christmas poem—this idea he executed at the request of the editor of Faber and Gwen—the poem bears no manifest reference to the name of Christ. From this, a point might be clear that the ‘journey’ is more allegorically suggestive of the spiritual progress of the soul; the emphasis is more on the process, outward and inward journeys that the humanity of an individual undertakes to expedite spiritual regeneration.

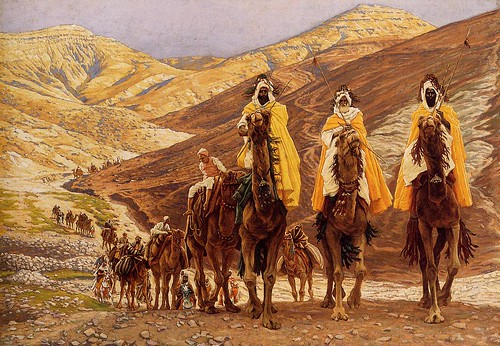

Here, the actual Birth—as is historically evident, the Magi ‘had evidence and no doubt’—witnessed by the three magi identified as Balthazar (king of Chalbia), Gasper(king of Ethiopia), and Melchior (king of Nubia), takes on the second matrix of exploration progress and change—the death of ‘old dispensation’ and the birth of the new.

The first stanza relates the long and convoluted ordeal of a journey of the caravans to Judea. The stanza carries a quotation from Lancelot Andrewe’s Nativity Sermons preached in 1622 to the Jacobean court. As is indicated in his essay ‘For Lancelot Andrewe’s, Eliot admired the former’s intellectual capacity upheld by his emotional sensibility that held the court in harmony. However, the first person speaker remembers the story of the event that happened many years prior.

‘Such a long journey’ begins in ‘the dead of the winter’ in solistio brumali— ‘just the worst time of the year’– through disparaging darkness, ‘the ways deep and the weather sharp’. Camels balked all too frequently from sores, vulgar camel men lacking ’liquor and women’ cursed and grumbled and ran away.

Deserted, smote they were haunted by warm memories of ‘the summer palaces on slopes’ and ‘silken girls bringing sherbet’; their fires often extinguished. Doubly taxed by the un-cooperative deceitful villagers, hostile city- dwellers, they walked even in the nights sleeping intermittently.

At the back of their minds, they were seduced to stop by voices ‘saying/That this was all folly’. It is a period of purgatorial contrition indeed. But a soul must move through desultory darkness and seek. This is the most detailed paragraph of the poem underlining the importance of ‘journey’ and search for life.

In the second stanza, the search is partly reciprocated. The speaker gets premonition although the signification is nebulous. The revelation is:

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line smelling of vegetation,

With a running stream and a water-mill beating in darkness.

Light and darkness, water and sterility dichotomies run in Eliot’s poetry. But whereas in earlier composition dominates the cornucopia of ash, ruins, broken images, and aridity, here, we first meet ‘vegetation’, ‘stream’ and ‘water-mill.

We also have stumbled upon a few haunting presences later to be recognized as Christian symbols however latent their implication is.

Three trees were the three crosses of the Calvary, at the feet of the mountains; the white horse of the Apocrypha symbolizes youth; six hands at the open door dicing for 30 pieces of silver bear the biblical allusion to the betrayal by Judas Iscariot for thirty pieces of silver also to the Roman soldiers dicing for the garments of Christ at the crucifixion.

Empty wineskins recall one of Christ’s parables about old and new. Yet no information of Birth was available until the third stanza incarnates the persona himself into the spirit of Christ. In an odd lukewarm way, ‘it was (you might say) satisfactory.

Once again the staccato exigency: ‘but set down/This set down/This’ as if finishing an epitaph (‘Every poem is an epitaph’, ‘Little Gidding’, Four Quartets).

The single (in contrast to the ‘we’ in the preceding stanzas)persona is at the fireside first, remembering (‘ALL THIS WAS A LONG TIME AGO) now; second, preparing for another journey and death (‘I WILL DO IT AGAIN’ and ‘I SHOULD BE GLAD OF ANOTHER DEATH’) and third, trapped in the paradox of Birth and Death.

The nagging doubt is: ‘were we led all the way for/ birth or death?’ Ordinarily birth is distinct from death. But the bitter and hard agony of this ‘Birth’ is death, our death. Birth is also stripping off of older worn-out selves:

….I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

New religion means the death –or chronic evolution–of the old one: the old ones now seem to be ‘an alien people clutching their gods’.

What are their functions? Memory liberates the indifference between attachment to self, to things, and to persons (warm memories of summer slope) and detachments from the same (from the old place). So the magus recollects. Second, ‘each action is a step to the block…this is where we start’ (ibid).

In the course of the poem, much experience takes place that is elliptical: shedding of the old dispensation. Without a listener, the memory fails and none to ‘set down’; the new persona is the new self-setting out for journey ‘another death. In a way to make an end is to make a beginning’.

It is not birth but death that brought a salvific longing for a new life. When in ‘Gerontion’ the narrator is waiting for the shower, the ‘hollow’ men grope in darkness and look for fixed eyes, the speaker has put behind him naiveté of the child; it is the supreme stage of desiring nothing. Unaware of the sacrifice, the magus—and the old garb of belief—is a sacrifice in itself, the immanent and the transcendental are concomitant.