Porgy and Bess symbolizes the end of the black musical tradition that flourished in the early part of this century. The play showed the height of white appropriation of what had previously been a black cultural form. All the creative talent backstage was white. This development had been occurring slowly, throughout the 1920’s, but black artists had often worked in a variety of creative capacities.

“Porgy and Bess” became a “black musical” in its most minimal sense, only as a definition of the color of the cast members. Neither the  plot nor the music was of black origin.

plot nor the music was of black origin.

Musical comedies seemed to be out of fashion in the 20’s due to the dismal revivals of “Shuffle Along” and “Blackbirds”. Black dramas with music, and particularly spirituals, remained in fashion. “The Green Pastures” is the best known example of this trend. As dramas about black life took on greater importance in the 1930’s, they often borrowed from the musical comedy traditions of the 1920’s. Serious drama, about black life in the rural south or in northern cities, managed to blend music into its structure. In the 20’s many of the dramas that had to do with black life, music became a necessity. In the 30’s this trend prevailed, musical elements of Afro-American culture were showcased primarily in dramas rather than in musicals.

In Hall Johnson’s “Run, Little Chillun!”, a folk drama about the conflict between the Christian and African religious heritage in black life, critics praised the marvelous choral music. While Johnson called his work a drama, Time suggested that he had written an opera, something rarely achieved or even considered by black artists working on Broadway.

Although the thought of an opera with a black cast and created by black talent was a rarity, it was not unprecedented. Bob Cole had spoken about an opera based on Uncle Tom’s Cabi, but the work remained uncompleted at his death. Scott Joplin had written an opera, “A guest of Honor”, while living in St. Louis in 1903. The opera had several performances in Missouri, but did go beyond the state’s borders.

Joplin’s second opera, “Treemonisha”, composed between 1905 and 1907, seemed more promising, Joplin died never seeing the play develop more then several auditions.

The first black performed opera on Broadway was Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s “Four Saints in Three Acts” which opened on Feb.20th, 1934. The production ran for 48 performances.

The 1935 production of Porgy differed from earlier black musicals in several ways. Porgy and Bess had virtually no blacks involved in either its production or the creation of the muscial. The show was also a prestige item, produced by the theater guild; earlier musicals were often mounted on a shoestring budget. This version was billed as an “opera”, or “folk opera”. At one point it seemed the Metropolitan Opera would present the show. It seems that Porgy and Bess had no direct creative links with its black musical predecessors. Nevertheless, without their presence the show might never have existed. The origin of the show was the Heywards hit play, “Porgy” (1927) it was clear that the origins of the project returned back to an earlier date.

George Gershwin had been interested in the rhythms of black music throughout the prewar years, and he attended many gatherings of black musicians, poets, and authors during the Harlem renaissance. He first attempted to create a jazz opera about black life in the early 1920’s. Entitled “Blue Monday Blues”, prepared by Gershwin and lyricist Buddy Desylva. Unlike “Shuffle Along” this play had white performers in blackface, which was the norm on Broadway at the time. The play was yanked after opening night after terrible reviews. Charles Darnton of the Evening World found the Gershwins piece “the most dismal, stupid, and incredible blackface sketch that has ever been perpetrated.” Critics ignored Gershwin’s operatic endeavors but the play and its revival “135th St.” showed that Gershwin had been interested in the creation of a black-themed opera some thirteen years before Porgy and Bess.

In the mid 20’s, Gershwin expressed interest in a new novel about black life called Porgy, written by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward in 1924. When Gershwin suggested to Heyward that they write a musical version, Heyward objected, since he and his wife were embarking on their own dramatization of the work for the Theater Guild. Porgy premiered on Broadway in October, 1927 and experienced one of the longest runs of any play with a black cast during the 1920’s. This story of a legless cripple, Porgy, and his love for the faithless Bess on Catfish Row in Charleston, South Carolina received generally favorable reviews. Not all black critics were happy, however. The predominance of superstition, gambling, and spirituals seemed to come from stereotypes that were common in white plays about black life that had appeared on Broadway since the 1920’s. Porgy did excel, however, in its acting talent. Director Rouben Mamoulian, a young Russian-American immigrant who had trained at the Moscow Art Theater, reviewed the black plays and musicals of the 20’s in his search for performers. Frank Williams was cast as Porgy and Evelyn Ellis as Bess. Maria was played by Georgette Harvey and Serena by Rose Mcclandon. Time magazine referred to this troupe as “seized from the dusky depths of the vagrant negro theater.

Although frustrated at first by the Heywards inability to participate in a musical version of Porgy. Gershwin kept on thinking of the play’s possibilities. He wrote to Dubose Heyward again in 1932, expressing his continued interest. “I am about to go abroad in a little over a week, and in thinking of ideas for new compositions, I came back to one I had several years ago- namely, Porgy, and the thought of setting it to music. It is still the most outstanding play that I know about the colored people.” He learned by return mail that he was not the only musical comedy composer interested in Porgy. Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II considered setting the play to music for Al Jolson. The news both distressed and confused Gershwin. Of this Gershwin wrote, “I think it is very interesting that Al Jolson would like to play the part of Porgy, but I really don’t know how he would be in it. Of course, he is a very big star, who certainly knows how to put over a song, and it might mean more to you financially if he should do it- provided that the rest of the production was well done. The sort of thing that I have in mind is a much more serious thing than Jolson could ever do.” Even at this early date, Gershwin voiced his preference for an “all-colored cast” for Porgy.

Both Gershwin and Dubose Heyward rearranged their schedules in the early 1930’s, trying to alleviate any money problems that might hinder their work. Heyward turned to Hollywood, working on screenplays, and Gershwin signed a lucrative radio contract. George moved to Folly Island, a small barrier island almost ten miles from Charleston, in order to observe the people of Heyward’s Porgy and continue working with the southern author. The composer spent the summer of 1934 listening to the Gullah’s speech and their music.

On his return, Gershwin spent almost eleven months in the composition of his new work, and another eight months in the orchestration. For the first time in his career he also tackled the vocal arrangements. Heyward provided the lyrics for songs in the first act of the new show and collaborated with Ira Gershwin, George’s brother, on the remaining two acts. As their work continued Porgy became Porgy and Bess. The change reflected the increased emphasis on Bess, but it also calmed Theater Guild producers who worried that the audience might confused it with the earlier version. Gershwin was also happy with the “operatic sound” of the new title- he compared his hero and heroine to “Pelleas and Melisande, Tristan and Isolde, and Samson and Delilah.” When it was finally completed in July, 1935, the 700 pages of music represented his most ambitious creation and his favorite composition. According to David Ewen, Gershwin’s first biographer, he “never quite ceased to wonder at the miracle that he had been its composer. He never stopped loving each and every bar, never wavered in the conviction that he had produced a work of art.”

Next Gershwin involved himself with the casting and production of his opera. Todd Duncan, the first Porgy, recalled that Gershwin was “going around the country looking for his Porgy.” Music critic Olin Downes recommended that Gershwin hear Duncan, who was teaching at Howard University as well as singing, but Gershwin rejected the idea because he felt that “he didn’t want any university professor to sing.” For his part, Duncan was not interested because Gershwin was “Tin Pan Alley and something beneath me.” Finally the two arranged a meeting during which Gershwin played and Duncan sang, and Gershwin asked Duncan to take the part of Porgy. Gershwin arranged an evening for Duncan with

Ira Gershwin and his wife, the Theater Guild board, and prospective backers. Duncan recalls that he was supposed to sing three of four songs, but “I sang an hour, an hour and a half.” Then Ira and George got out the score of Porgy and Bess and sang the entire opera in “their awful, rotten voices.” Duncan continues “I just thought I was in heaven. These beautiful melodies in this new idiom it was something I had never heard. I just couldn’t get enough of it when he ended with I’m on My Way I was crying. I was weeping.”

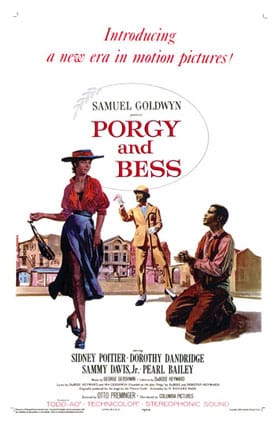

Gershwin chose to have Porgy and Bess given a Broadway run at the Alvin Theater rather than a full operatic production, to assure more performances, and the word opera was avoided. The first cast of nineteen singing principals included, with Duncan, Anne Brown as Bess, John W. Bubbles as Sportin’ Life, Warren Coleman as Crown, and the Eva Jessye Choir; Rouben Mammoulian produced and directed, and Alexander Smallens conducted. Porgy and Bess tried out in Boston and opened in New York on October 10, 1935 for a disappointing run of 124 performances; it was years later before the show’s backers got their money back, and more.

Porgy and Bess was George Gershwin’s longest and most ambitious creation, but it was not truly successful during his lifetime. Some of the songs had achieved popularity before Gershwin’s death in 1937, but the work earned real approval and favor only after the 1940 Theater Guild presentation of a slightly revised version. For years it was performed more frequently in Europe, where it was considered a true American opera. Porgy and Bess received its first uncut production in Houston in the 1970’s, conducted by John DeMain, to great approval, and it was finally produced at the Met some 50 years after the first production. It is probably the only opera founded on 1920’s and 30’s jazz which has survived past the post- World War II period, when composers began to use jazz satirically.

Unfortunately, Porgy and Bess inspired no copies. Had the art of the black musical been thriving, the Gershwin show would have encouraged other producers, writers, and composers to experiment further. But Gershwin’s show was yet another failure in a dying genre. If the Theater Guild and acclaimed composers could not market a black-performed musical show, what hope could there be for others? In this sense, Porgy and Bess marked the bottom in the history of black musical comedy, symbolizing the end of tradition in black musical theater on Broadway.