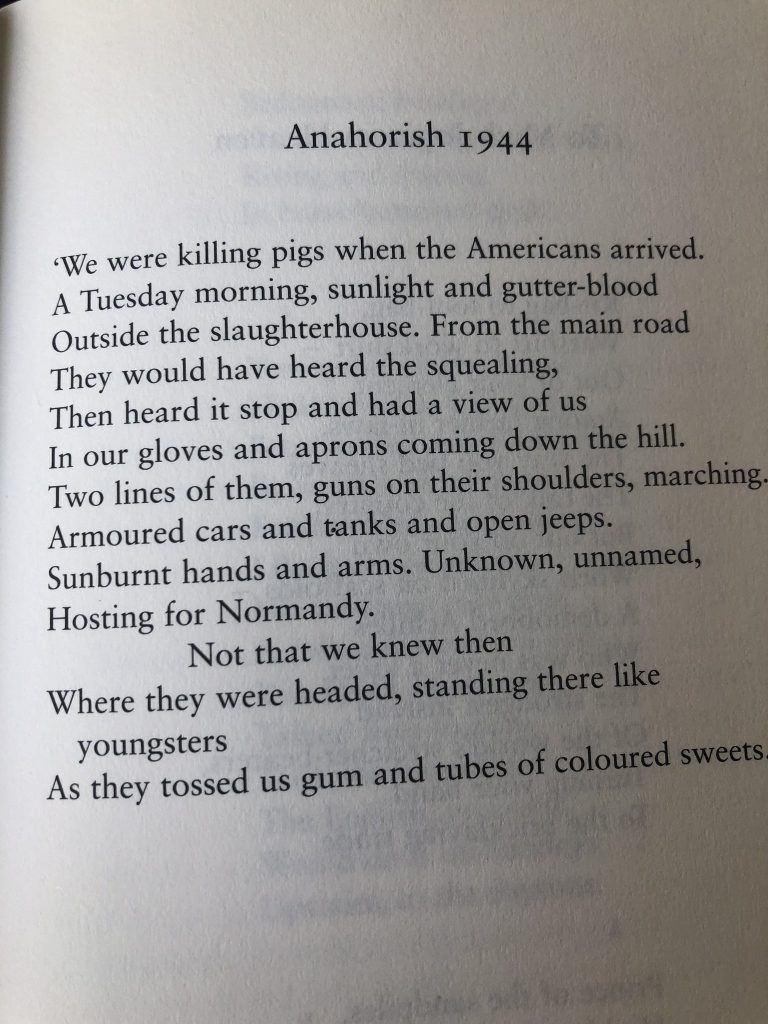

Our shared human experiences can be often hard to unravel and may seem buried under a complex web of conflicting and contrasting ideologies. It can be easy to forget that we are united in the basic aspects of living that are part of our physical condition. Irish poet Seamus Heaney has demonstrated this through his poems ‘The Tollund Man’ (1973), following the journey of the bog person found in Denmark, and ‘Anahorish’ about his childhood home.

Poetry is able to illuminate these shared experiences of death and birth, connection and trust in nature, and the ability to find beauty and make meaning. Heaney’s ‘sonic engineering’ is an essential part of this, with the deliberate construction of lines to create assonance, consonance and meter. However, Heaney’s ability to create meaning from the mixing of different contexts and words cannot be discounted.

Themes of death and birth are described in the poems—a feature of all human life—explaining how they show the cycle of end and beginning.

‘The Tollund Man’ deals explicitly with death and killing, acknowledging the ‘cap, noose and girdle’ around the Tollund Man, the ‘stockinged corpses’ of labourers and the ‘skin and teeth’ of young brothers, as well as the ‘old man-killing parishes’ in Jutland. ‘The Tollund Man’ was written one year after the Bogside Massacre outside Derry in 1972, and the death of the young boys may have been a reference to another killing in the 1920s. In both massacres, only Catholic people were killed. In all situations, people were ‘sacrificed’ for a cause.

The Tollund Man for a pagan goddess and the fertility of the bog, and the others—in some sick, sad way—the freedom of other Catholics. It is clear that Heaney is drawing parallels between the Tollund man and the victims of violence in Northern Ireland. In Part 2, where this is explained, the rhythm becomes more emphasised, favouring the consonance of ‘t’ and ‘d’. This is clear in the second stanza of the Part, where ‘the scattered, ambushed/flesh of labourers/stockinged corpses/laid out in the farmyards’ has a distinct meter.

The sound qualities therefore imbue the sense of violence and destruction, which contrasts with the calm quality of Part 1 describing the Tollund Man. This indicates that Heaney sees their death as a tragedy. By drawing these links listeners are exposed to the complexities and causes of death, and how some are ‘at one’ with nature and others are not (the remains of the brothers were ‘flecking the sleepers…for miles along the lines’, they could not be ‘used’ by nature and start new life).

This relates to our shared understanding of tragedy, as the Tollund Man died peacefully in his own ‘sad freedom’, whereas the Irish were killed violently. It also establishes that death in which we are comfortable with—death that isn’t unjust—is where life can happen afterwards (the seeds ‘caked in his stomach’ allowed the Tollund Man to ‘make germinate’). This appeals to our desire for renewal and our ability to make happiness out of something sad.

‘Anahorish’ is more implicit about the cycle of life and death, though still carries through many of the same themes. The idea of death and rebirth is shown in the fact that water starts in the ‘pregnant belly’ of the hills (Morris, 1981) and ends as broken ice. This is also done through sibilance in the last line, ‘at wells and dunghills’, expresses the full cycle of the birth of the ‘ll’ in the hill, the gushing, streaming water of ‘ss/sh’, the crisp airiness of ‘a’ and the exhale of ‘w’ to the closure and death at ‘ll’.

The ‘w’ is already associated with water and the ‘ll’ is associated with hills (established in the beginning). This tells the story of how the water has travelled from the hills, through the river in ‘the bed of the lane’ and has died a ‘soft’ death in the rolling landscape of the hill. Through the reference to the last word ‘dunghills’ (small piles of manure used for fertiliser), we know that after the ‘winter evening’ there will be life again. Through context and allusions, as well as narrative told by the sound devices, we gain an understanding of the cyclical nature of our own lives and deaths.

Heaney makes several connections between man made and natural features, rendering each with an equal sense of beauty to imply our universal need for connection to nature.

‘Anahorish’ mentions ‘hills’ (monumental mounds of earth), springs (fissures in hills from where the water comes from), wells (man-made springs) and dunghills (small mounds of dung for fertiliser).

This encapsulates natural and man-made features of the landscape, implying that they are each equally important for human survival and happiness. Water is also followed throughout the poem from when it is ‘washed into/the shiny grass’ from the spring to ‘darken[ing] cobbles/in the bed of the lane’ to when humans ‘go waist deep in mist/to break the light ice’. Humans are able to live in harmony with nature and change, relying on it and carrying out its functions.

Even though many of us could not relate to Heaney’s experience of living with nature so closely, we understand it’s significance through his yearning. The overall tone of the poem is soft and uplifting (shown by the high level of assonance and overall beauty of the intermixing of sonic devices and literal description of the landscape to create imagery), which makes us feel included in Heaney’s experience and love for Anahorish.

The lines where Heaney describes the sonic features of the name ‘Anahorish’ is almost ode-like. This reinforces our understanding with his connection to the place and thus emphasises the importance of natural connections. In ‘The Tollund Man’, similar emphasis is put on our connection to nature. However, it is more literal, as the Tollund man is turned, with the ‘dark juices’ of the bog, ‘peat-brown’ with a ‘gruel of winter seeds/caked in his stomach’. He becomes part of it. Figurative language—‘gruel’ and ‘cake’—is used here to describe the seeds that will ‘make germinate’ from the Tollund Man’s body, which is again a situation where man-made items are used to carry out the function of nature.

This also positions ‘man’ as the method of this function. If we look into Heaney’s rural childhood, we can understand how everyday tasks (such as his father planting potatoes) inform his view that humans have a function in nature. Heaney portrays the Tollund Man as accepting of this sacrifice he is making for the earth through the relatively peaceful tone and slow rhythm.

His face is ‘mild’, ‘his last gruel’ rests in his stomach, humble (‘naked except for/[his] cap, noose and girdle’), and he is complacent as ‘dark juices [work]/him to a saint’s kept body’. There is a high level of consonance of ‘k’ and ‘t’ used to emphasise his unchanged body. Such consonance carries through Part 1 in which his body is described, maintaining a slow, steady pace (‘caked in his stomach’…‘naked except’…’tightened her torc’ etc…).

The reason why archaeologists believed he was willingly sacrificed for the benefit of others was because of the calm expression on his face, which is something Heaney has communicated through language. By identifying our place in nature, Heaney has allowed us to see more clearly our joint need to be part of it.

‘The Tollund Man’ explores Heaney’s personal choice to intermesh different faiths and nature, demonstrating our that our desire to find comfort in an ‘otherworldly’ is not necessarily embedded in strict religious sects. At the end of the second stanza, the narrator expresses his wish to ‘stand a long time./Bridegroom to the goddess,’ indicating that the Tollund Man entered a union with the goddess when he entered the bog. She then ‘tightened her torc on him’.

A torc is a gold neck ring worn around the neck, a celtic status symbol, which could also allude to a wedding ring. The goddess ‘opened her fen/those dark juices working/him to a saint’s kept body’, imitating a sort of ‘marriage’ in which nature turns human remains into a life-source that can ‘make germinate’. The entire process of decomposition is compared with the religious processes of marriage.

Heaney then states he ‘could risk blasphemy/consecrate the cauldron bog/our holy ground and pray’, as it is the dominant ideology that the two are contradictory. He acknowledges the conflict between the two religions—paganism and Christianity (Heaney was Catholic)—yet accepts worshipping both. The wording/diction has been chosen with connotations in mind, bringing together these religions and comparing them to natural processes.

This is supported by the steady pace of the rhythm, the stanza has the same, subtly indistinct meter which is pierced with sharp ‘c’ and ‘g’ sounds, which lends a sense of stability and clear thinking. This shows it is not a rushed, turmoiled decision. This is also supported by the fact that he moves on quickly to talk about the massacres, indicating he is not all that troubled by the conflict between the religions.

In Heaney, the two can live side by side, indicating that he is not subscribing to a religion for the sake of it but rather the ‘truthfulness’ of religion that resonates with him and mimics natural processes. Heaney does not suggest we need religion, but rather some form of spirituality or trust and connection to nature.

By linking the sound structure of the poem ‘Anahorish’ with the landscape he describes, Heaney emphasises the human element in the creation of meaning.

The first stanza of ‘Anahorish’ starts with a mix of ‘ll’ sounds, Heaney’s ‘“place of clear water”, the first hill in the world’. The ‘ll’ is a lulling, fluid sounds that rolls. ‘Hill’ is also is slightly onomatopoeic in the sense that saying ‘ll’ is almost a downwards motion, following the course of the water down a slope. This creates a situation in which the sonic qualities of the poem ‘carry out’ the literal events, meaning these sounds fulfill our expectations of the movement of the water that ‘washed into the shiny grass’.

The last two lines of the first stanza are dominated by ‘ss’ and ‘sh’ sounds, which also resembles gushing water. The ‘a’ sounds of ‘grass’, ‘and’ and ‘dark’ articulate the experience of drawing in a light, airy breath. This makes us feel uplifted and light, maintaining our high ground on the hill. We then sink into ‘the bed of the lane’ as the ‘a’ of ‘and’ subsides into ‘darkened cobbles’. These words are rubbly, heavy and ‘thick’ with consonants that lower us into the landscape. Heaney himself then analyses the word ‘Anahorish’, a ‘soft gradient of consonant, vowel meadow’.

He describes how the word embodies the subtle gradualness of the landscape, how it rises and dips, just like the first two stanzas of the poem itself. This is an old Gaelic device called dinnseanchas—looking at how the aesthetic qualities of place names are part of creating a ‘sense of place’. This again emphasises the importance of human tradition in creating place and meaning. ‘A’ sounds abound until we slide into ‘w’s, which resonate with ‘winter evenings’. The ‘w’ is almost pushed out of us by the nature of it’s sound but also the pace of the poem—forcing us out of breath.

This is supported by the full stop after ‘winter evenings’—the first since ‘Anahorish’—signalling that we can take another breath. ‘W’s subside into ‘l’s, a soft close. Slowly we are then re-introduced with the ‘ll’ sound with the mention of ‘dwellers’. This can also be seen in ‘The Tollund Man’, where there is a heavy, iambic rhythm in Part 1 in lines that concern the earth, such as ‘consecrate the cauldron bog’. Consonants like ‘c’, ‘s’, ‘t’, ‘l’, ‘d’, ‘n’, ‘b’ and ‘g’ are broken with vowels. This gives the lines a ‘rough’ texture, heavy like the loamy soil of a bog.

The sonic qualities themselves mimic the landscape, which can only be accentuated and nuanced by our own verbal expression. Such expression adds to the beauty of the poem and contributes to the ‘truthfulness’ and strength of its meaning by fortifying and illustrating it. By incorporating human input as a necessary part of the poem, Heaney has highlighted our shared ability to enhance the beauty of such a poem and therefore make meaning.

Death, rebirth, connection to nature and beauty are all part of the human experience as they are embedded in our physicality. Heaney has communicated this not just through figurative language and poetic devices (such as assonance, consonance and meter), but also through word choice that alludes and connotates to the background of specific events and ideas. By emphasising our shared similarities, Heaney shows that we generally desire the same things—happiness, connection and creativity.