In studying and understanding the politics and artistic ideologies of film not in the popular “Hollywood” tradition, films of different cultures must be examined to explore the political and social history of the struggles for cultural identity. The film becomes a means of consciousness raising and of creating political awareness. Films of revolution and social change cross all cultural boundaries and bring to the screen revolutionary movements in developing and underdeveloped countries. The power of film is such that it not only reflects society in its own image; they can cause society to create itself in the image of the films.

This, unfortunately, has proved to be a battle for black men and women as they have been depicted in a far from flattering view since the beginning of the medium. African Americans have been forced to endure constant racism and discrimination projected at them through movies since the technology was created. Through the determination of many intelligent filmmakers, African Americans have been able to create a depiction of their culture as they see fit; and in the process, creating anti-racial films committed to social change.

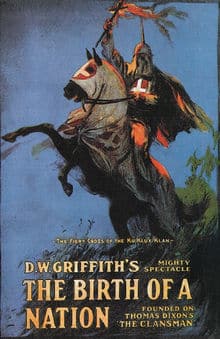

At times, the screen has predicated against progress by fixing certain concepts and stereotypes in the public mind and artificially reinforcing the notion of their continuing usefulness. The victims of these stereotypes were mainly African-American. Blacks were, for the most part, misrepresented subjects to be exploited by the medium of film since it was created; the most popular example being, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a  Nation (1915). Although hailed as the most successful and artistically advanced film of its time, it ignited race riots and it directly influenced the 20th century reemergence of the Klan. Birth of a Nation locked misconceptions about race into a technologically innovative movie that gripped viewers with its new ability to convey the full flavour of events and feelings. The Birth of a Race (1918), two years in the making and perhaps three hours in length, began as a response to Griffith’s film. But its succession of producers and backers lost touch with the original concept.

Nation (1915). Although hailed as the most successful and artistically advanced film of its time, it ignited race riots and it directly influenced the 20th century reemergence of the Klan. Birth of a Nation locked misconceptions about race into a technologically innovative movie that gripped viewers with its new ability to convey the full flavour of events and feelings. The Birth of a Race (1918), two years in the making and perhaps three hours in length, began as a response to Griffith’s film. But its succession of producers and backers lost touch with the original concept.

Nonetheless, it inspired George P. Johnson and his brother, Noble, to found the Lincoln Motion Picture Company to carry forward the quest for a black cinema, only to fail because of a nationwide influenza epidemic that shuttered theaters. As the American movie industry gradually moved to California after World War I, little new opportunities arose for the African American. Blacks generally played out conventional roles as chorus girls, convicts, racetrack grooms, boxing trainers, and flippant servants. The sameness of the images led to the first boom of race movies that were made by black, and often white, producers specifically for black audiences. George and Noble Johnson made as many as four such films that were black versions of already defined Hollywood genres – success stories, adventures, and the like – all of them since lost. As World War II progressed, creators of race movies disappeared due to the short rations of film stock. Yet black activists and their government together pressed filmmakers to address wartime racial injustice. In response, federal agencies made several movies of advocacy. First among them in distribution to both army and civilian theaters was the United States War Department’s The Negro Soldier (1944), written by Carlton Moss, who also starred in the film. Late in the war, the government commissioned or inspired short civilian films on the theme of equitable race relations, among them Don’t Be a Sucker, It Happened in Springfield, and The House I Live In (which won an Oscar in 1947 as the best short film). The Government Manual for the Motion Picture (1942) recommended the use of ‘colored’ soldiers and servicemen with foreign names as a way of stressing national unity. The general conception was that pictures of racial integration might help to allay racial tensions at home. Documentaries, meanwhile, were beginning to showcase more liberal attitudes. Janice Loeb and Helen Levitt’s The Quiet One (1947) caught the dedication that social workers gave to black juveniles. The United Auto Workers sponsored an animated cartoon, The Brotherhood of Man (1947), which took up the fate of racism in postwar America.

Of all African American filmmakers of the era, Oscar Micheaux dominated his age. More than any other known figure, Micheaux took up themes that Hollywood left untouched: lynching, black success myths, and color-based caste. Above all, Micheaux saw his films as “propaganda” designed to “uplift the race.” In the 1930’s, his films represented a radical departure from Hollywood’s portrayal of blacks as servants and brought diverse images of ghetto life and related social issues to the screen for the first time. During his career, Micheaux made 35 movies. Most were stories about the lives, loves and perils of middle-class blacks. With his fifth movie, Within Our Gates (1920) Micheaux attacked the racism portrayed in the most highly acclaimed silent movie of all time The Birth of a Nation. In his movie, Griffith depicted blacks as lazy alcoholics who raped white women. Micheaux turned the table on Griffith, filming a scene where a white man tries to rape a black woman, using exactly the same lighting, blocking, and setting as the black on white rape scene in The Birth of a Nation. Unfortunately for Micheaux, Within Our Gates came out right after the race riots, which plagued America throughout the summer of 1919. Black and white officials feared further violence if Within Our Gates was shown and they forced Micheaux to edit out controversial scenes. Micheaux, however, turned around and booked other theatres to show the “uncut version” to even bigger audiences.

Around 1950, the Committee for Mass Education in Race Relations was set up with the intent to “produce films that combine entertainment and purposeful mass education in race relations.”

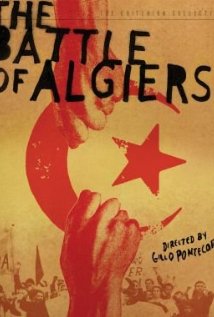

At this time, films were beginning to provide momentum for the Civil Right Movement that was to take place in the 1960s. Films became more  political during these times challenging the views of the ignorant. Costa-Gavras’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) was adopted as a favourite film of the Black Panthers, while Anthony Harvey’s Dutchman (1967) was considered revolutionary by critics. A new wave of films was to follow the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The impact of the Civil Rights Movement along with the assassination of the Movement’s leader was felt across America. New waves of films were to be embarked upon by Hollywood labeled “blaxploitation.” As a movie genre, blaxploitation refers to a series of films in which African-American characters and their lifestyles are presented in a manner that reinforces often negative stereotypes. Many critics of 70s blaxploitation films believed these movies pandered to the lowest of black so called “ghetto” images, while borrowing heavily from mainstream Hollywood genres no longer used. There were black westerns, sci-fi fantasies and even kung-fu films. But despite mediocre performances by the actors and shoestring budgets, the hip talk, sex appeal, and messages of black power made blaxploitation movies instant hits with black audiences. This portrayal becomes the ideal by which young Black men and women live their lives, forcing them to become adolescent adults with guns and out of wedlock babies. Secondly, this portrayal tends to dehumanize Black men in the eyes of the world. As Adolph Hitler demonstrated, it is much easier to annihilate a race after that race has been lowered to a subhuman status in the eyes of society.

political during these times challenging the views of the ignorant. Costa-Gavras’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) was adopted as a favourite film of the Black Panthers, while Anthony Harvey’s Dutchman (1967) was considered revolutionary by critics. A new wave of films was to follow the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The impact of the Civil Rights Movement along with the assassination of the Movement’s leader was felt across America. New waves of films were to be embarked upon by Hollywood labeled “blaxploitation.” As a movie genre, blaxploitation refers to a series of films in which African-American characters and their lifestyles are presented in a manner that reinforces often negative stereotypes. Many critics of 70s blaxploitation films believed these movies pandered to the lowest of black so called “ghetto” images, while borrowing heavily from mainstream Hollywood genres no longer used. There were black westerns, sci-fi fantasies and even kung-fu films. But despite mediocre performances by the actors and shoestring budgets, the hip talk, sex appeal, and messages of black power made blaxploitation movies instant hits with black audiences. This portrayal becomes the ideal by which young Black men and women live their lives, forcing them to become adolescent adults with guns and out of wedlock babies. Secondly, this portrayal tends to dehumanize Black men in the eyes of the world. As Adolph Hitler demonstrated, it is much easier to annihilate a race after that race has been lowered to a subhuman status in the eyes of society.

The financial success of Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) came as a surprise to Hollywood’s major studios who instantly attempted to cash in. Melvin Van Peebles projected a new image of a black hero in his film that he wrote, directed and starred in. The message of Sweetback is that, if you can get it together and stand up to the Man, you can win. “Of all the ways we’ve been exploited by the Man,” Van Peebles writes, “the most damaging is the way he destroyed our self image.’ Black Panther leader Huey Newton urged the black community to see the film more than once since it attempts ‘to communicate some crucial ideas and motivates us to a deeper understanding and then action based on that understanding.” The portrayal of Black men as gangsters and thugs is damaging in a number of ways. There have been four episodes of filmmaking about Afro-Americans: Hollywood films portraying blacks before World War II, Hollywood films after that war, films made by black independents such as Oscar Micheaux and Spencer Williams before WWII, and the black exploitation movies of the late 1960s and early 1970s. There has been an addition to the previously mentioned episodes known as the new black cinema. The new black cinema was born out of the black arts movement of the 1960s, out of the same concerns with a self-determining black cultural identity.

What separates the new black cinema from these other episodes is its freedom from the mental colonization that Hollywood tries to impose on all its audiences, black and white. Asserting that black expression could be appreciated on its own terms, this new black cinema aimed to preserve black culture both within the Hollywood system and apart from it. A younger generation of filmmakers embraced Van Peebles, Micheaux, and African filmmakers as their cultural models. For the first time women joined black filmmakers’ ranks. New distributors, including the Black Filmmakers Foundation, California Newsreel, and Women Make Movies, Inc., aimed at select audiences and academic circles rather than mass markets. The best known of the new black filmmakers during the 1980s and 1990s was probably Spike Lee. Spike Lee’s breakthrough independent feature, She’s Gotta Have It (1986), was a “welcome change in the representation of blacks in American cinema, depicting men and women of color not as pimps and whores, but as intelligent, upscale urbanites.” By the late 1990s, the steadily expanding black presence in American film seemed to assure a solid future for the new black cinema.

The medium of film has a surface realism which tends to disguise fantasy and make it seem true. Since the creation of the technology to capture moving images, African Americans have been depicted in an unfair fashion. Popular films would inflict the values of ignorant, racist filmmakers as people went to discover them. It took a lot of struggle and perseverance for filmmakers to enjoy the luxury of freedom available to them today. Hollywood was never considered an ally to African Americans who wanted to depict their reality as it really was. Independents had to struggle to finance films which were not Hollywood-friendly and many seized to continue because of this obstacle. The pioneers of anti-racist films; the men and women who triumphed over hardships to create a piece of art true to their heart and culture are credited for providing the backbone for social change. However, there is no argument that blacks still have distances to go in receiving a fair and honest portrayal in movies and television.