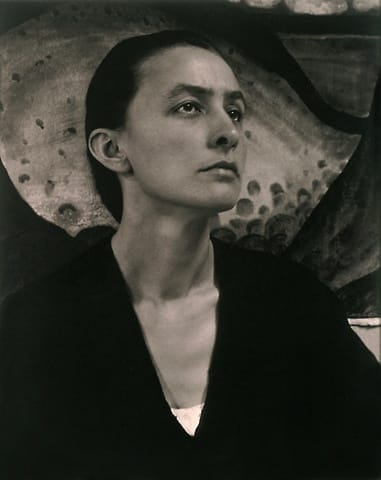

During the early twentieth century, women suffered from discrimination and inferiority. An exception to this case was Georgia O’Keeffe, who captured the attention of the world with her paintings. She was the only female of her generation to be accepted as a professional artist. Art critic Henry McBride noted, “Mona Lisa got but one portrait of herself worth talking about, O’Keeffe got a hundred….Everybody knew the name. She became what is known as a newspaper personality.” Georgia O’Keeffe knew exactly what she wanted from life and was not frightened to reach out for it. She left her mark in an artistic field believed to be exclusively for men.

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe was born in 1887 in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. She was a well-behaved, self-disciplined child. At a very early age she  decided where life was going to lead her: she was going to be a painter (Berry 23). Not taking in consideration her family’s opinion, O’Keeffe started to sketch.

decided where life was going to lead her: she was going to be a painter (Berry 23). Not taking in consideration her family’s opinion, O’Keeffe started to sketch.

One of her first sketches was of a man bending over. She worked on this piece for quite a while, trying to get the position of the legs correctly. But when she turned the drawing upside down, she noticed that the man looked fine with his legs up in the air. O’Keeffe recalled, “I thought it a very funny position for a man, but after all my effort it gave me a feeling of real achievement to have made something– even if it wasn’t what I had intended.”

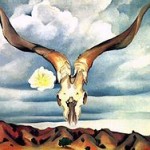

After graduating from college, O’Keeffe set out to the southwest taking up jobs as an art teacher in different schools and universities. Her journey in Texas and its surrounding states during the years of 1912 to 1916 helped O’Keeffe define her personal style of painting. She spent a great deal of time exploring the wild, empty spaces. She observed the shapes found in nature and translated them into very personal abstractions (Berry 39). O’Keeffe found her greatest inspiration to be the landscapes of this vast and colorful region.

One day in 1915, O’Keeffe shut herself inside her room and placed her drawings and paintings against the walls. Seeing in them the influence of others, she decided to throw them away. Above all, she refused to conform, to make herself a prisoner of the ideas of others (Streifer 182).

O’Keeffe was first discovered when a friend of hers, Anita Pollitzer, showed her charcoal sketches to the famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz. He decided to exhibit them in his avant-garde New York gallery, 291 5th Avenue. When O’Keeffe found out about this she went mad and demanded that her paintings be taken down. Stieglitz, however, convinced her to leave the work on the walls; eight years later, he convinced her to marry him (Streifer 183). He also held twenty one-woman shows for O’Keeffe, beginning in April 1917 (Streifer 183).

Life in the Big Apple started drying up O’Keeffe’s sources of inspiration. After long discussions with her husband, O’Keeffe finally decided she would move to New Mexico, with or without him. The southwest, she said, “That was my country– terrible winds and a wonderful emptiness.” Her sojourn in New Mexico brought about the time of O’Keeffe’s greatest productivity. In 1940, she even bought a ranch house; she settled there permanently after Stieglitz’s death in 1946. Museums all over the northeast invited O’Keeffe to exhibit and put up major retrospectives. Years later, O’Keeffe also started traveling, painting clouds as seen from above.

O’Keeffe was the only woman of her generation to have made a successful career out of art. Many other women were painters for up to half a century, only to obtain recognition decades later. O’Keeffe’s recognition as an artist came sooner, when she was in her early thirties ( Castro 71). Most artists at the time were men who learned to accept and even praise the work of O’Keeffe. She was an original artist who defined her own self-image.

In 1986, almost blind and deaf, O’Keeffe died. All throughout her life she never expressed fear of death. The only thing she felt was regret. Regret of not being able to come back. She once said, “When I think of death I only regret that I will not be able to see this beautiful country anymore, unless the Indians are right and my spirit will walk here after I’m gone.” O’Keeffe led her life just the way she wanted to lead it. She flourished as a woman artist in an age where art was a field predominated by men. She remained true to herself, expressing everything on her mind through her paintings. Georgia O’Keeffe is indeed a model for all women and a key figure in the development of modern American art.