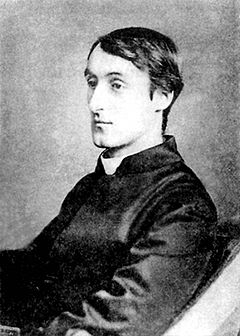

Gerard Manley Hopkins, born on July 28 1844, was the eldest of eight children of a London marine insurance adjuster. Besides writing books about marine insurance Gerard’s father, Manley, also wrote a volume of poetry. His mother on the other hand was a very pious person. She was actively involved in the church and impressed her religion on Gerard. He attended Highgate School where his talent for poetry was first shown. Some sources say he won as many as seven contests while enrolled at Highgate.

Gerard in 1864 enrolled at Balliol College, at Oxford, to Read Greats (classics, ancient history, and philosophy). At this time in his life he  wanted to become a painter, like one of his siblings. His plans changed when he, and three of his friends were drawn in to Catholicism. He was received by the Church of Newman in October of 1866. After having taken a first class degree in 1867, he taught at the Oratory School, Birmingham. Two years later he decided to become a Jesuit when he burned all his verses as too worldly. When he entered as a Jesuit he wrote no poems. although the thought of crossing the two vocations constantly crossed his mind. Then in 1875 he told his superior how moved he felt by the wreck of the Deutschland, a ship carrying five nuns exiled from Germany. His superior expressed his wish that someone would write a poem about it.

wanted to become a painter, like one of his siblings. His plans changed when he, and three of his friends were drawn in to Catholicism. He was received by the Church of Newman in October of 1866. After having taken a first class degree in 1867, he taught at the Oratory School, Birmingham. Two years later he decided to become a Jesuit when he burned all his verses as too worldly. When he entered as a Jesuit he wrote no poems. although the thought of crossing the two vocations constantly crossed his mind. Then in 1875 he told his superior how moved he felt by the wreck of the Deutschland, a ship carrying five nuns exiled from Germany. His superior expressed his wish that someone would write a poem about it.

Hopkins having his motive wrote his first major work. He sent his poem to long time friend Robert Bridges who was put off by the poem and called it ”presumptuous juggelry.” But Hopkins stood his ground, knowing he had something of worth. His poem brought together his own conversion and the chiefs nun’s transfiguring death. God’s wrath and God’s love with the face of an epigram. Hopkins faith was a source of anguish. He said he never wavered in it, but that he never felt worthy of it. Hopkins felt that language must divorce itself from such archaisms as ”ere,” ”o’er,” ”wellnigh,” ”whattime,” and ”saynot.” But Hopkins invented many new words like: beechhole (trunk of a beech tree), bloomfall (fall of flowers), bower of bone (body), firedint (spark), firefolk (stars), unleaving (losing leaves), and leafmeal (leaf and piecemeal). Gerard Manley Hopkins led a life that he thought was good. He lived a life that met both his mothers and fathers expectations. He like his father wrote poetry, but unlike his father didn’t like to publicize his works. And like his mother he was very actively involved in the church, becoming a priest. But unlike his mother didn’t devote his whole life to religion. Gerard unfortunately only lived to be 45 when he died of typhoid. He was the professor of classics at University College, Dublin for many years before he passed away.

When Yeats said that Hopkins’ style was merely “the last development of poetic diction” he spoke like a contrary old man. Hopkins’ small and idiosyncratic productions, much of it fragments, must have seemed to Yeats a threat to what had been already achieved without it. Hopkins poems blended of natural and learned elements, and that its vivid surface leads on occasion not only to clarity but also to darkness. In many of his poems it is difficult to get its true meanings. Yvor Winters blamed it on the convenient scapegoat of “Romantic” individualism. But many others blame it on Hopkins’ desire for discipline. After suffering ill health for several years and bouts of diarrhea, Hopkins died of typhoid fever in 1889 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, following his funeral in Saint Francis Xavier Church on Gardiner Street, located in Georgian Dublin.