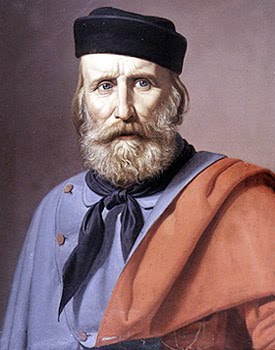

Giuseppe Garibaldi, b. Nice, France; July 4, 1807, d. Caprera, Italy; June 2, 1882. He was known as Italy’s most brilliant soldier of the Risorgimento (the Italian Unification), and one of the greatest guerrilla fighters of all time. While serving (1833-34) in the navy of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, he came under the influence of Giuseppe Mazzini, the prophet of Italian nationalism.

He took part in an abortive republican uprising in Piedmont in 1834. Under a death sentence, he managed to escape to South America, where  he lived from 1836 to 1848. There he took part in struggles in Brazil and helped Uruguay in its war against Argentina, commanding its small navy and, later, an Italian legion at Montevideo. The warrior achieved international fame through the publicity of his elder Alexandre Dumas. Wearing his colorful gaucho costume, Garibaldi returned to Italy in April 1848 to fight in its war of independence. His exploits against the Austrians in Milan and against the French forces supporting Rome and the Papal States made him a national hero. Overpowered at last in Rome, Garibaldi and his men had to retreat through central Italy in 1849.

he lived from 1836 to 1848. There he took part in struggles in Brazil and helped Uruguay in its war against Argentina, commanding its small navy and, later, an Italian legion at Montevideo. The warrior achieved international fame through the publicity of his elder Alexandre Dumas. Wearing his colorful gaucho costume, Garibaldi returned to Italy in April 1848 to fight in its war of independence. His exploits against the Austrians in Milan and against the French forces supporting Rome and the Papal States made him a national hero. Overpowered at last in Rome, Garibaldi and his men had to retreat through central Italy in 1849.

Anita, his wife and companion-in-arms, died during this retreat. Disbanding his men, Garibaldi again escaped abroad, where he lived successively in North Africa, the United States, and Peru. The “hero of two worlds” could not return to Italy until 1854. In 1859 he helped Piedmont in a new war against Austria, leading a volunteer Alpine force that captured Varese and Como. In May 1860, Garibaldi set out on the greatest venture of his life, the conquest of Sicily and Naples. This time he had no governmental support, but Premier Cavour and King Victor Emmanuel II dared not stop the popular hero. They stood ready to help, but only if he proved successful. Sailing from near Genoa on May 6 with 1,000 Red shirts, Garibaldi reached Marsala, Sicily, on May 11 and proclaimed himself dictator in the name of Victor Emmanuel. At the Battle of Calatafimi (May 30) his guerrilla force defeated the regular army of the king of Naples. A popular uprising helped him capture Palermo–a brilliant success that convinced Cavour that Garibaldi’s volunteer army should now be secretly supported by Piedmont.

Garibaldi crossed the Strait of Messina on August 18-19 and in a whirlwind campaign reached Naples on September 7. On October 3-5 he fought another battle on the Volturno River, the biggest of his career. After plebiscites, he handed Sicily and Naples over to Victor Emmanuel when the two met near the Volturno on October 26. Angered at not being named viceroy in Naples, however, Garibaldi retired to his home on Caprera, off Sardinia. Nevertheless, he continued to plot to capture the Papal States. In 1862 the Italian government, fearing international complications, had to intercept him at Aspromonte, where he was wounded in the heel. When he led another private expedition toward Rome in 1867, French troops halted him at Mentana. Subsequently, during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), Garibaldi led a group of volunteers in support of the new French republic. For about two years thereafter Garibaldi lived the life of a farmer on Caprera. In 1870 he offered his services to the French government and fought with his two sons in the Franco-Prussian War. Rome was annexed to Italy in October 1870, and Garibaldi was elected a member of the Italian parliament in 1874.

In his last years he sympathized with the developing socialist movement in Italy and other countries. Garibaldi’s autobiography, Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi, was published in 1887. Without Garibaldi’s support, the unification of Italy could not have taken place when it did. A gifted leader and man of the people, he knew far better than Cavour or Mazzini how to stir the masses, and he repeatedly hastened the pace of events. Disillusioned in later life with politics, he declared himself a socialist.