Paul Laurence Dunbar attended grade schools and Central High School in Dayton, Ohio. He was editor of the High School Times and president of Philomathean Literary Society in his senior year. Despite Dunbar’s growing reputation in the then small town of Dayton, writing jobs were closed to black applicants and the money to further his education was scarce. In 1891, Dunbar graduated from Central High School and was unable to find a decent job. Desperate for employment, he settled for a job as an elevator operator in the Callahan Building in Dayton.

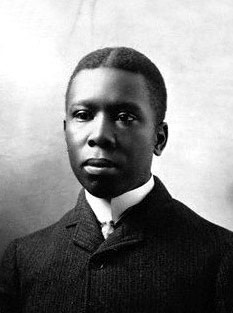

The major accomplishments of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s life during 1872 to 1938 labeled him as an American poet. Dunbar had two  poetic identities. He was first a Victorian poet writing in a comparatively formal style of literary English. Dunbar’s other identity was that of the dialect poet, writing lighter, usually humorous or sentimental work not merely in the Negro dialect but in other varieties as well: Irish, once in German, but very frequently in the hoosier dialect of Indiana. There is good reason to assert, however, that the sources of Dunbar’s dialect verse were in the real language of the people. The basic charge of this criticism can be stated in the words of a recent critic, Jean Wagner. Dunbar’s dialect is, he says, “at best a secondhand instrument, irredeemably blemished by the degrading things imposed upon it by the enemies of the Black people” (Revell, Paul Laurence Dunbar, pg. 84). One of the most popular of Dunbar’s dialect poems was and is “When Malindy Sings” which builds upon the natural ability of the race in song and is acknowledged to be Dunbar’s tribute to his mother’s spontaneous outbursts of singing as she worked in the kitchen. The message of the poem is of praise for simplicity of spirit and the love of God.

poetic identities. He was first a Victorian poet writing in a comparatively formal style of literary English. Dunbar’s other identity was that of the dialect poet, writing lighter, usually humorous or sentimental work not merely in the Negro dialect but in other varieties as well: Irish, once in German, but very frequently in the hoosier dialect of Indiana. There is good reason to assert, however, that the sources of Dunbar’s dialect verse were in the real language of the people. The basic charge of this criticism can be stated in the words of a recent critic, Jean Wagner. Dunbar’s dialect is, he says, “at best a secondhand instrument, irredeemably blemished by the degrading things imposed upon it by the enemies of the Black people” (Revell, Paul Laurence Dunbar, pg. 84). One of the most popular of Dunbar’s dialect poems was and is “When Malindy Sings” which builds upon the natural ability of the race in song and is acknowledged to be Dunbar’s tribute to his mother’s spontaneous outbursts of singing as she worked in the kitchen. The message of the poem is of praise for simplicity of spirit and the love of God.

“Sympathy” (“sym” meaning with and “pathy” meaning feeling) is a very emotional poem about a caged bird trapped with no way to escape. “A poem like ‘Sympathy’- with its repeated line, ‘I know why the caged bird feels, alas!’- can be read as a cry against slavery, but was probably written out of the feeling that the poet’s talent was imprisoned in the conventions of his time and the exigencies of the literary marketplace” (Revell, Paul Laurence Dunbar, 73). Dunbar’s first stanza in the poem uses the word ‘alas’ to mean anxiety. Throughout “Sympathy” the caged bird is enduring distress due to his life’s limitations. “And the faint perfume from its chalice steals- I know what the caged bird feels!” These two lines from “Sympathy” express the caged bird’s thought of someone stealing his ideas and thoughts. “I know why the caged bird beats his wing till its blood is red on the cruel bars” expresses rage the caged bird feels and the physical abuse the caged bird endures trying to escape. During this period in Dunbar’s life, he met George Washington Carver in Dayton, James Whitcomb Riley in Indianapolis, and he became lifelong friends with Dr. H.A. Tobey, a Toledo psychiatrist.

The major accomplishments of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s life during 1872 to 1906 also labeled him as being a short story writer. Although Dunbar experienced much criticism in his early career, he also enjoyed a good deal of success. These successes, unfortunately, did not come without some personal sacrifices and tribulations. He encountered rifts with his closest friends and associates, often the result of his business and artistic decisions. One such confrontation occurred when Dunbar decided to sell certain works to George Horace Lorimer of the Saturday Evening Post and Harrison Smith Morris of Lippincott’s, two longtime friends of Dunbar, to the dissatisfaction of his agent. Dunbar responded by explaining:

The last artistic accomplishment of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s life was labeled as a serious novelist. Dunbar wrote four novels between 1897 and 1901. The first two of these works, The Uncalled (1898) and The Love of Landry (1900) are “white” novels in which all the characters are white and no reference is made to the presence of Black people. The other two novels, The Fanatics (1901) and The Sport of the Gods (1902) are considered to be “black” novels. Dunbar’s first novel, The Uncalled, was written in England in 1897, and was published to little commercial success. Critic Benjamin Brawley considers the work “only partly a success” and remarks quite unjustly upon “the lack of local color and the mediocre quality of the English” (qtd. in Revel p. 65). Robert Bone opines that it is Dunbar’s most successful novel and remarks misleadingly that it is “widely regarded as his spiritual autobiography” (Bone, pg. 39). The Uncalled is the story of the childhood and young manhood of Frederick Brent. The story opens with the death of his mother in circumstances of poverty. She has been abandoned by her drunken husband and sells her soul to the devil. The plot thickens when the question arises as to who will take care of young Frederick.

The Love of Landry, Dunbar’s second novel, was a major commercial disappointment. The writing in this book is fairly relevant to the circumstances that brought Dunbar to Colorado and his experiences there. In The Fanatics Dunbar tries to bring out the essential human values of brotherly love, love between man and woman, family loyalty, tolerance, and forgiveness that underlie and finally resolve the conflicts of fanatical devotion to a cause. The Sport of the Gods is an attempt by Dunbar to depict Black Americans living in social currents of his time.

Dunbar proved to be very disheartened by the fact that his audiences and publishers relished so heavily on his works of dialect poetry. He felt that acceptance of his serious work- primarily his standard English poetry- faltered because of the demand for his dialect pieces. It is commonly felt that Dunbar’s perception of the severity of plantation life for slaves was diffused and diluted by the stories he heard from his mother as a youngster. His mother, like his father, was a former slave, and her stories often failed to express the more brutal aspects of plantation life. Dunbar’s works have often been widely criticized because of this “watering down” of the atrocities of slavery (Revell). Dunbar’s poems in literary English, his short stories and novels all rely more or less on traditional forms and conventional characterization.

Works Cited

Baker, Houston A. Jr. “Paul Laurence Dunbar: An Evaluation.” Black World. 21 Nov. 1971: 30-37.

Brawley, Benjamin. Paul Laurence Dunbar: Poet of his People. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1936.

Cunningham, Virginia. Paul Laurence Dunbar and his Song. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1947.

Metcalfe, E.W.,Jr. Paul Laurence Dunbar: A Bibliography. Metachen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1975.

Revell, Peter. Paul Laurence Dunbar. Twayne Publishers: 1979.

Revell. Peter. Paul Laurence Dunbar. Boston, Twayne Publishers: 1979. Pg. 84.

Ibid, pg. 37.

Ibid, pg. 73.