Henry David Thoreau, author and environmentalist, was the first to write about the elephant in the room and have a  large audience read it. His writing made people acknowledge that we need to start conserving our natural resources. With cod almost extinct, and the Staples Thesis complete, it was time for America to change. This would prove difficult though, with the progressive era just beginning, everyone was all about consumption and production. Using vast amounts of natural resources to build railroads and factories to aid in the construction of more trains to ride the ever increasing amount of railroads towards more factories. It was impossible to even think of conservation. But one thing people liked just as much as building giant empires was traveling. Exotic and wild destinations around the country were once reserved for the exclusive. With the ever expanding railroads, it became increasingly possible for more people to travel to remote locations deep within uncivilized territory. This was both exclusive and wild. Prime for America’s wealthy population willing to pay the price and go the distance. Here started a new revolution in tourism and a new awareness of the need to conserve and preserve.

large audience read it. His writing made people acknowledge that we need to start conserving our natural resources. With cod almost extinct, and the Staples Thesis complete, it was time for America to change. This would prove difficult though, with the progressive era just beginning, everyone was all about consumption and production. Using vast amounts of natural resources to build railroads and factories to aid in the construction of more trains to ride the ever increasing amount of railroads towards more factories. It was impossible to even think of conservation. But one thing people liked just as much as building giant empires was traveling. Exotic and wild destinations around the country were once reserved for the exclusive. With the ever expanding railroads, it became increasingly possible for more people to travel to remote locations deep within uncivilized territory. This was both exclusive and wild. Prime for America’s wealthy population willing to pay the price and go the distance. Here started a new revolution in tourism and a new awareness of the need to conserve and preserve.

At the turn of the century, President Theodore Roosevelt, WWI, and the Roaring Twenties gave birth to a whole new generation of people. Roosevelt laid the cornerstone for the National Park System to create areas “as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” The eyes of the American people were opened and they started to realize that we could not go on shooting everything that walks on four legs, flies, or swims, chopping down trees that were in the way of “progression”. They saw that natural, untouched land often holds immeasurable value. Value that goes beyond the almighty dollar. This realization gave birth to the Migratory Bird Act of 1918, regulating and sometimes denying the ability to hunt some migratory birds. Before this act, President Roosevelt saw that the breeding grounds of some birds were being trampled with human influence, so he created a bird sanctuary in Florida that would be the bases for the National Park Service which was signed into law in 1916 by President Woodrow Wilson.

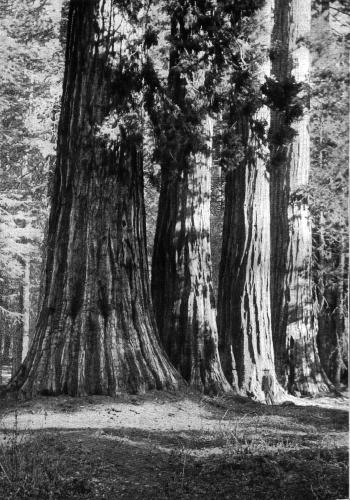

Yellowstone National Park was the groundbreaker for the almost sixty national parks that we have today in America, and many others throughout the rest of the world. In 1876, the park gave infrastructure, limited as it was, for people to get out into the wilderness and discover its beauty. People travelled from all over the country by train to the nearest station, then rolled for miles with horse and buggy on less than favorable roads. They used it as an escape from their noisy, dirty, and busy city lives. “Environmental history is always about human interaction with the natural world…”[1] The parks are what helped give the American population an opportunity to get hands on with nature and start to understand what so many people are missing out during a time when seemingly everything we did was meant to destroy it. This still holds true today. Tourism is what makes the national and many state parks successful and economically viable. “Forests were usually regarded as obstacles to development, elements to be feared, or combated, or simply as something that ‘blocked the settler’s view.’”[2] The parks helped overturn this mindset by letting people see forests in a different way and spur a conservation movement.

many others throughout the rest of the world. In 1876, the park gave infrastructure, limited as it was, for people to get out into the wilderness and discover its beauty. People travelled from all over the country by train to the nearest station, then rolled for miles with horse and buggy on less than favorable roads. They used it as an escape from their noisy, dirty, and busy city lives. “Environmental history is always about human interaction with the natural world…”[1] The parks are what helped give the American population an opportunity to get hands on with nature and start to understand what so many people are missing out during a time when seemingly everything we did was meant to destroy it. This still holds true today. Tourism is what makes the national and many state parks successful and economically viable. “Forests were usually regarded as obstacles to development, elements to be feared, or combated, or simply as something that ‘blocked the settler’s view.’”[2] The parks helped overturn this mindset by letting people see forests in a different way and spur a conservation movement.

Trains are what allowed people to travel long distances at the turn of the century. Without them, there would not have been any sort of tourism in the northwest region of the United States. Without them, there would not have been any push to protect land and resources. The name of the game is education. Without people knowing what is out there, there would have been no reason to not keep chopping down trees westward and hunting animals to extinction. Trains are the ultimate reason why people had the chance to go to the remote areas that housed the parks because there were no paths traversable by foot, and commercial airliners were still in the distant future. For those who couldn’t afford the price of travel, they had the option to read about it in a book by John Muir titled Our National Parks. He prefaces the sketches and writing by saying “… I have done the best I could to show forth the beauty, grandeur, and all-embracing usefulness of our wild mountain forest reservations and parks, with view to inciting the people to come and enjoy them, and get them into their hearts that so at length their preservation and right use might be made sure.” It is this book that helps establish Muir as a writer and catches the eye of the American population. It had a similar effect to that of Rachel  Carson’s A Silent Spring.[3]

Carson’s A Silent Spring.[3]

One of the first recommendations to set aside land for public use was by John Conness, a California congressman. In 1864 during the Civil War, he proposed to protect sixty square miles of land, including the Yosemite Valley. Abraham Lincoln signed a law to protect land he had never seen thousands of miles away.[4] John Muir would later show up in the valley and use the written word to promote the landscape. A conservationist, Gifford Pinchot found the trees to have great economic potential as timber. And President Roosevelt also shared the wonder for Yosemite.

This trio are the defining persons of environmental history. Different views on what should be done with the vast wilderness, but united in that they knew something needed to be done to protect the natural wonders. A Scot, a business man, and a president who spoke softly and carried a big stick shaped the American environmental movement. With their combined knowledge and power, they were able to make significant progress in conserving wildlife and kick starting the movement of environmentalism by literally laying down the paths that would open the secluded wilderness to the tourism industry. It is the tourism industry that prompted the government to start protecting land and draw attention to conservation. North America went from not having any land protected by law in 1850 to having hundreds of square miles signed into law by 1920. Momentum had been created and the movement continued on through times of poverty and times of war.

[1] K. Jan Oosthoek, What is Environmental History, 1. Origins. Environmental History Resources, 2005, accessed October 12, 2015, https://www.eh-resources.org/what-is-environmental-history/#more-34

[2] Foster, Janet, Working for Wildlife: The Beginning of Preservation in Canada, University of Toronto Press, 1978

[3] Muir, John, Our National Parks, Boston and New York Houghton, Mifflin and Company, The Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1901

[4] Burns, Ken, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, accessed December 7, 2015, http://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/