Born on May 26th 1895 in New Jersey, Dorothea Lange had a rough childhood. Contracting polio before the age of eight, she walked with a limp for most of her life. Instead of studying and working on an education, Lange spent most of her time wandering the streets on New York. Finding pictures along these walks and collecting her favorites is thought to have sparked her interest in photography. She called this “acting like a photographer observer”. It was during these walks that she realized the beauty of the unknowing person. She continued her walks until perfecting her “cloak of invisibility”, which is watching without appearing to.

While studying to become a teacher, by her parent’s request, Lange worked both being a secretary and occasionally restoring photographs at  the local photography Due to an unhappy employee quitting before a job appointment, Lange was sent to replace him. From then on she held her position as a studio photographer. Lange soon began to work for herself with commissioned works with only two years of formal instruction with Clarence White under her belt.

the local photography Due to an unhappy employee quitting before a job appointment, Lange was sent to replace him. From then on she held her position as a studio photographer. Lange soon began to work for herself with commissioned works with only two years of formal instruction with Clarence White under her belt.

Before marrying her first husband, a painter named Maynard Dixon, Dorothea Lange packed up and moved across the country to San Francisco, California, and opened her very own portrait studio. She birthed her first son at the age of thirty, and her second just three years later. These years were more focused on raising her boys and being a housewife than furthering her career.

Sparking her best early work, the depression of 1929 lured Lange out of her studio and into the streets. It was here Lange photographed the poor and homeless. During this period she photographed one of her most popular works, “White Breadline Angel”.

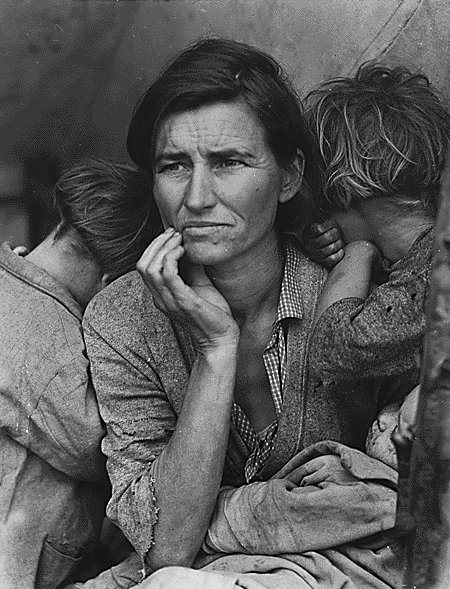

In 1934, just months after her first show in the gallery of Oakland, Lange was offered a job to continue the path of her work of photographing the less fortunate people of the depression by the department of Resettlement Administration. Enduring not only the change from studio to documentary photography due to the depression, Dorothea’s first marriage began to break up. By 1935 she was divorced from her first husband. However, working with the young Dr. Paul Taylor occasionally, produced a relationship that resulted in marriage soon after her split up. During her trips with the R.A. (Resettlement Administration), which varied from days to months, Lange’s most popular work was taken. These trips allowed her to photograph urban slums, homeless shelters, and migrant workers such as cotton pickers. Another photograph during these trips turned out to be the most famous work in Lange’s portfolio, named “Migrant Mother”.

At the end of a trip in 1936 Lange “approached the desperate mother ask[ing] no questions [about] her name or history… She was 32.” Lange was quoted saying “There was a sort of equality about it… I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment.” Lange had a way of capturing the soul of her subjects in a single expression. The disparity and worry for her children is clearly shown engraved into her face, aging her much more than she really is. Because of the emotion captured and the viewer response of the “Migrant Mother” it is now used as the trademark for both the Resettlement Administration and Farms Security. Also, because it has been her and that time periods most re printed  photograph, many people say that she could not ever outshine that one picture.

photograph, many people say that she could not ever outshine that one picture.

Lange continued to work for the R.A. through their name change to Farmers Security Administration. Though, in the years that followed her improper training began to become more apparent, the intense connection with the subjects she photographed allowed people to look past this. Lange proved herself again however, producing a book of her documentary photographs, which expressed her deep connection with her subject matter. Lange’s next undertaking seemed almost unnoticed as timing of its release coincided with World War II. Collaborating with her husband, Lange and Taylor began work on their book recording the effects the depression had on the American people. It was not successful due to the opening of jobs and the need for soldiers.

Soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor Lange was offered a job by the War Relocation Authority to record the “process of interning the Japanese-American citizen during 1942, under the executive order 9066.” The result of this assignment again awarded Lange much acclamation. Twenty-six of her photographs recorded were reproduced fueling her fame with no end in sight. Bombarded with sickness and health problems, Lange spent the next twelve years of her life out of the public eye. She restricted her photography to mainly her family members. It was during this period when she was quoted, as saying “Where there is perhaps a province in which the photograph can tell us nothing more than what we see with our own eyes, there is another in which it proves to is how little our eyes permit us to see.”

When she felt well enough to continue, she began her work with Life magazine. Her first was a collaboration with Ansel Adams documenting a Mormon Community. She then escaped to Ireland where she planned to capture the true “old country” way of life. Lange chose to keep all of her Ireland photographs untitled because of her connection with the country. This trip gave Lange the opportunity to get back to her old way of photographing the emotion and honest inner person. She felt a connection not only with the people, but also with the soil of Ireland itself. This connection is clearly shown in each work from this period. It was said that Lange’s pictures “are Ireland, her heart and soul.” and that the people seem to “be” Ireland also. They work in the soil as a part of life, resulting in the soil and the people becoming one.

Lange’s quote accompanying the above photograph encapsulates the entire essence of Ireland, the people, and what she was trying to do. She was quoted saying “I saw a dark figure approaching… and as he passed, he was pure Ireland, he was just made out of that wet, limey soil.”

In the following years Lange tagged along with her husband in his trips to other countries. She assembled a collection of 500 works from one of the trips to Egypt. In the last two years of her life created an exposition of her work for the Museum of Modern Art, and two films about her incredible life. Lange’s broad and busy life covered many years and many different events. Each contributed to her popularity and success. Due to cancer, Dorothea Lange passed away on October 11, 1965. Her work has preceded her reputation around the world, and will continue to do so. Her photograph of the migrant mother will continue to influence people for as long as it is reprinted. It relates to the inner feeling of despair in all of us, and carries along the feeling of utter hopelessness of that time.

Dorothea Lange photographed many subjects in her lifetime and, not to our surprise, they are still being reprinted. Lange was quoted many things in her lifetime, but none encapsulates the true essence of her photography like her quote “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” This statement helps readers realize the sight Lange had. Her ability to see the beauty and inner self of her subjects is something all of us should try and copy.