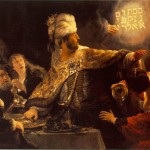

In Leyden, Holland, the year of 1606, the renowned artist known as Rembrandt van Rijn was born. At age seven he began attending grammar school where he studied the classics, Latin, possibly Hebrew, and the Bible. Seven years later Rembrandt’s father made plans for sending him to a university. Rembrandt, whose only desire was to paint, refused. From the years 1620 to 1623, Rembrandt studied in Amsterdam under Pieter Lastman. It his Lastman who probably first exposed Rembrandt to Renaissance painting and Christianity as a major theme. This style of painting Christian topics though, was more one of expressing fantastic stories, than teaching the Bible. By age nineteen, Rembrandt began to search for his own style. For the next seven years he painted in a grandiose and lucid technique, painting the stories of Samson, David and Goliath, Judas, and Saint Paul. These works would soon bring him much fame and wealth, but only for as long as he was willing to refrain from the avant-garde.

Throughout his career, Rembrandt van Rijn went from Amsterdam’s famous painter–enjoying great wealth, to the impecunious, prodigal  son–awaiting forgiveness. Rembrandt’s life was a tragic one full of misfortune, loss and grief, leading him to rely greatly on religious solace. No matter what his social status, fortune or demeanor, Rembrandt always stayed near to his faith in the Bible and its teachings. Though he was never much a man of chastity or religious practice, his faith in Christianity was unwavering. The purpose of this paper is to study Rembrandt the artist, how he was affected by social life and, more pointedly, his religious beliefs. It is not certain whether Rembrandt ever belonged to any particular church, though many believe he may have been a Mennonite for a short period. What is known for certain though, is that just prior to his death in 1669, the only possession of a then destitute Rembrandt consisted of a single book: the Holy Bible.

son–awaiting forgiveness. Rembrandt’s life was a tragic one full of misfortune, loss and grief, leading him to rely greatly on religious solace. No matter what his social status, fortune or demeanor, Rembrandt always stayed near to his faith in the Bible and its teachings. Though he was never much a man of chastity or religious practice, his faith in Christianity was unwavering. The purpose of this paper is to study Rembrandt the artist, how he was affected by social life and, more pointedly, his religious beliefs. It is not certain whether Rembrandt ever belonged to any particular church, though many believe he may have been a Mennonite for a short period. What is known for certain though, is that just prior to his death in 1669, the only possession of a then destitute Rembrandt consisted of a single book: the Holy Bible.

In 1632, at age 26, Rembrandt left Leyden to live in Amsterdam, the center of intellectual life in Holland. Two years later he married Saskia van Uylenburch who was from a prestigious family. The Rembrandt of this time was a man of pleasure and passion, whose artwork had made him a very popular painter and quite rich. His great joy over his wealth and popularity can be seen in paintings such as Rembrandt & Saskia. Rembrandt’s style at this point combined a fluid, naturalist technique with baroque gesturing. During this period in his life, Rembrandt became a very large spender, placing large bets and buying most any piece of art he saw. The method he used in buying a painting was to make his first bid so outrageously high that the other bidders would not even bother to compete for the piece.

While other artists in Holland were painting landscapes and social life, Rembrandt continued to focus on the stories of the Bible. Even though much of his subject matter dealt with the Bible though, Rembrandt was not a true Biblical painter. Paintings like The Raising of Lazarus (1632) depicted Christ as if he were more a sorcerer than the Son of God. The influences of Jan Sanders van Hemessen (1500-1566) and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1573-1610) are most evident in Rembrandt’s The Calling of St. Matthew, which uses the method of making biblical scenes worldly and common. The influence of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) can be seen in Supper at Emmaus (1629). The use of light to create depth and shadow gives the painting a theatrical aspect common in Rembrandt’s work at this time.

His early years in Amsterdam were ones of fame and fortune, but Rembrandt was a man who kept to himself, staying at home with his wife Saskia and constantly developing his work. In 1641, after several miscarriages, Saskia gave birth to their son Titus. Despite Rembrandt’s rather esteemed social stature, he remained the recluse, often using Saskia and Titus as models for his paintings. At this time Rembrandt’s work caught the interest of Prince Henry Frederick, who commissioned Rembrandt to produce a series of paintings, but Rembrandt was not a man to paint as others told him and soon his style would change.

In 1642, after less than eight years of marriage and only a year after the birth of their son, Saskia died, marking the beginning of Rembrandt’s years of grief and loneliness. That same year he hired a widowed housemaid, Geertghe Dircx, who would soon become very close to him. At this time in his life, it is believed that Rembrandt may have joined the Mennonite church, but he was probably later kicked out for his then degrading status, if not for his relationship with Geertghe. In 1649 Rembrandt dismissed Geertghe; she died a year later in a mad house.

During the years of 1642 through 1648, Rembrandt slowly changed his artwork to a style devoted entirely to inducing spirituality. When comparing Supper at Emmaus (1648) to its 1629 counterpart, the drastic change in technique is quite evident. Rembrandt dropped the theatrical quality in his use of layout and lighting; depicting Christ head on, under normal lighting. Christ is placed in the center beneath an arch, giving the painting a symmetrical layout. As Rembrandt became more dejected in life, he worked harder at striving to depict biblical scenes that were pure and of the utmost holiness. His painting Night Watch is noted for its excellent use of chiaroscuro. The eyes are deep and sorrowful and the expression seems to be that of triumph over great inner-struggle. It is believed that during this time Rembrandt may have been subject to the Copernican revolution, and surely this art piece seems to show that Rembrandt was reclaiming his solitude. Unfortunately, his drastic change in style cost him his popularity, which of course also meant his income.

In the early Renaissance, art was a way to teach the Bible to those who could not read. Since Christianity spread most quickly among the lower class, who were illiterate, this was especially important. As the years past though, literacy increased and art became less biblical. Calvinism had some effect on this because there was a fear of idol worship and much art was destroyed as a result. The Protestant Reformation did not condemn artwork, but instead placed its emphasis on Bible study. The year 1648 was one of victory over Spain and so many artists in Holland based their artwork on this subject. Rembrandt was still focusing on biblical scenes, becoming truer to the spiritual aspects to be found. His artwork was no longer based on the Renaissance idea of humanism and the glory of man, but instead depicted man as humble before God.

Many believe that Rembrandt may have been the most influenced of all artist by the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation was undoubtedly compatible to Rembrandt’s newly found homage to God’s grace and his rejection of human glory and beauty. Rembrandt was also very fond of the Bible. His mother read the Bible to him every day, and it’s believed that many of Rembrandt’s paintings depicting a woman reading the Bible are probably of his mother. Rembrandt himself, unlike most artist of the time, actually read the whole Bible and painted many different stories as compared to the same four to five repeated by artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Peter Paul Rubens. Unfortunately, Rembrandt’s prestige continued to decline despite his spiritual enlightenment.

In 1651 Rembrandt met Hendrickje Stoffles, but was unable to marry her because of Saskia’s will. He had already spent the inherited money, which was only his if he never remarried, and by this point Rembrandt was very poor due to his prior life of frivolous spending. A year later Hendrickje gave birth to their daughter Cornelia. This combined with Hendickje’s four appearances before the church council for living in sin, completely ravished any esteem society had once held for him.

Four years later Rembrandt was forced into bankruptcy and had to sell all of his acquired paintings. During these last years in his life, Rembrandt seemed to focus on themes dealing with the mercies of God. From 1656 to 1561 he produced eight paintings of Christ as Gethsemene, as compared to one in the years prior. Rembrandt never painted a single Last Judgment, but instead painted stories dealing with the themes of having a second chance such as Raising of Lazarus and Prodigal Son. It seemed as if these topics of humanity and forgiveness were ones Rembrandt hoped to have for himself. In 1662 Hendrickje died. Titus died in 1668, less than a year after being married. During this time Rembrandt lived in virtual seclusion, rarely leaving his home. The last piece Rembrandt would paint before his death in 1669 was The Return of the Prodigal Son. Rembrandt died in the service of a moneylender; his only procession was a Bible. Holland’s greatest painter was ironically given the modest burial of a peasant.

Rembrandt van Rijn evolved from paintings of his merry self wearing a red velvet hat – thrusting forth a glass of wine, to the stoic Bible scenes reminiscent of Michelangelo’s later work. Though not a man of religious practice, he was a man of great faith. Rembrandt was willing to put his beliefs before material goods, social status, and wealth. The influence of religious reformation and his tragic social life sent Rembrandt’s work in a direction that, like many great artists, caused him to be scorned by his own generation, but would later be appreciated and studied forever.

References:

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 9.

Franz Landsberger, Rembrandt, The Jews and The Bible (Philadelphia, 1946), 5.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 9.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 60.

Franz Landsberger, Rembrandt, The Jews and The Bible (Philadelphia, 1946), 174-75.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 10.

Franz Landsberger, Rembrandt, The Jews and The Bible (Philadelphia, 1946), 9-10.

Arthur M. Hind, Rembrandt (Cambridge, MA, 1932), 1.

William H. Halewood, Six Subjects of Reformation Art (Toronto, 1982), 23, 25, 44-45.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 11.

Arthur M. Hind, Rembrandt (Cambridge, MA, 1932), 1,3.

Franz Landsberger, Rembrandt, The Jews and The Bible (Philadelphia, 1946), 7.

Arthur M. Hind, Rembrandt (Cambridge, MA, 1932), 14.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 12-13, 66.

Franz Landsberger, Rembrandt, The Jews and The Bible (Philadelphia, 1946), 92-93.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 13-14.

William H. Halewood, Six Subjects of Reformation Art (Toronto, 1982), 4-5, 19.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 9, 21-22.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 15.

Arthur M. Hind, Rembrandt (Cambridge, MA, 1932), 7.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 16.

Arthur M. Hind, Rembrandt (Cambridge, MA, 1932), 7.

W. A. Visser ‘T Hooft, Rembrandt and The Gospel (London, 1957), 17.

Franz Landsberger, Rembrandt, The Jews and The Bible (Philadelphia, 1946), 11